Archaeologists working at the ancient city of Pi-Ramesses, near modern Qantir in Egypt’s Nile Delta, have discovered children’s footprints preserved in mortar and fragments of a large painted wall, both dated to roughly the era of Pharaoh Ramesses II. The city is traditionally regarded as the site of the Biblical exodus.

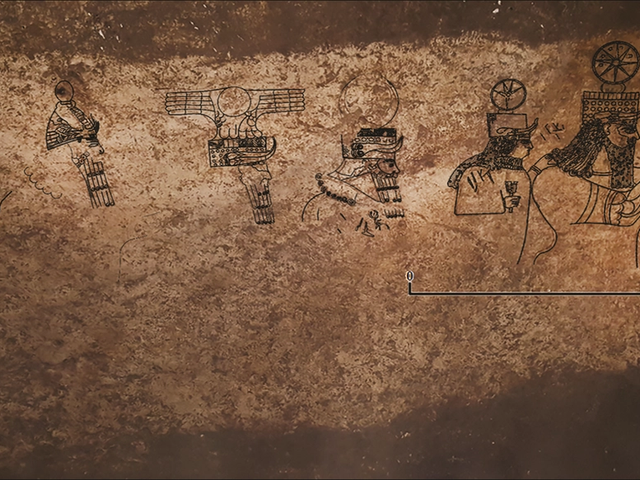

The team, from the Roemer- und Pelizaeus Museum Hildesheim, uncovered fragments of a large painted wall that was used to fill an ancient mortar pit. Due to the size of the motifs, the scenes may originally have decorated the entrance to a temple, a chapel, or were perhaps from a nearby palace, says the field team’s director, Henning Franzmeier.

Intriguingly, there are some indications that a fresco technique, similar to that used by contemporary Mycenaean Greeks, might have been used by the ancient artisans to create these paintings, though further study is needed to confirm this. Due to the early stage of research, no scenes have currently been reconstructed, but the team hopes to piece together the fragments during future seasons of fieldwork.

Analysis of footprints also preserved in the mortar suggests they were left by children, aged between three and five years old. “Were they just playing or were they working there, trampling and mixing the mortar?” Franzmeier says. “If they were only three to five years of age, I think they’re a little bit too young. But on the other hand, what would kids be doing playing at a construction site?”

In use from around 1300-1100 BC, the city of Pi-Ramesses, built under King Ramesses II, has been under investigation since the early 1980s. Previous discoveries have included chariot workshops with an exercise court for horses (where hoof imprints have also been preserved in the ground) and a stable complex with enough space for around 480 animals.