Increasingly stringent censorship in China under president Xi Jinping’s regime could be a barrier to the otherwise unparalleled growth of the art market in mainland China, a Western dealer has said.

Speaking during Shanghai Art Week in November, as the West Bund Art & Design and Art021 fairs opened alongside the Shanghai Biennale and numerous exhibitions, the dealer—who wished to remain anonymous—said the week compares to Frieze week in London or Fiac week in Paris. “It has the same intensity. But the government will have a big say in the growth of this art market, because the last few years have not shown an opening in attitudes, but almost the opposite.”

With regard to censorship, the dealer said he thought China would become more liberal when he started exhibiting there a few years ago; instead, it is getting more strict: “Every year, we have a few works rejected, but it is getting [to be] more and more—it makes me feel uncomfortable.”

Navigating Chinese bureaucracy and cultural sensitivities is a challenge to the many foreign galleries and having Chinese-speaking staff—or even dedicated registrars—is becoming a necessity. A Chinese employee of another international gallery, who also wished to remain anonymous, sees worrying parallels with the “brainwashing” in the run-up to the Cultural Revolution as controls become increasingly stringent in the five years since Xi Jinping has been in office. “As a Chinese citizen, I am very worried,” she says. “So much propaganda is appearing, particularly in Beijing—where there used to be advertising, now you see government slogans.”

West Bund Art & Design and Art021 help their foreign exhibitors with the approval process for works they wish to display since, for imported art, censorship happens at two levels. First it must be approved by the local cultural bureau, then by customs, before being shipped. Works that are shipped before approval is granted (due to the length of time it takes to ship a work from, say, Europe or the US to China) risk being impounded. Local artists and galleries do not have to deal with customs (unless importing works), and only large museum shows need pre-approval from the city’s cultural bureau.

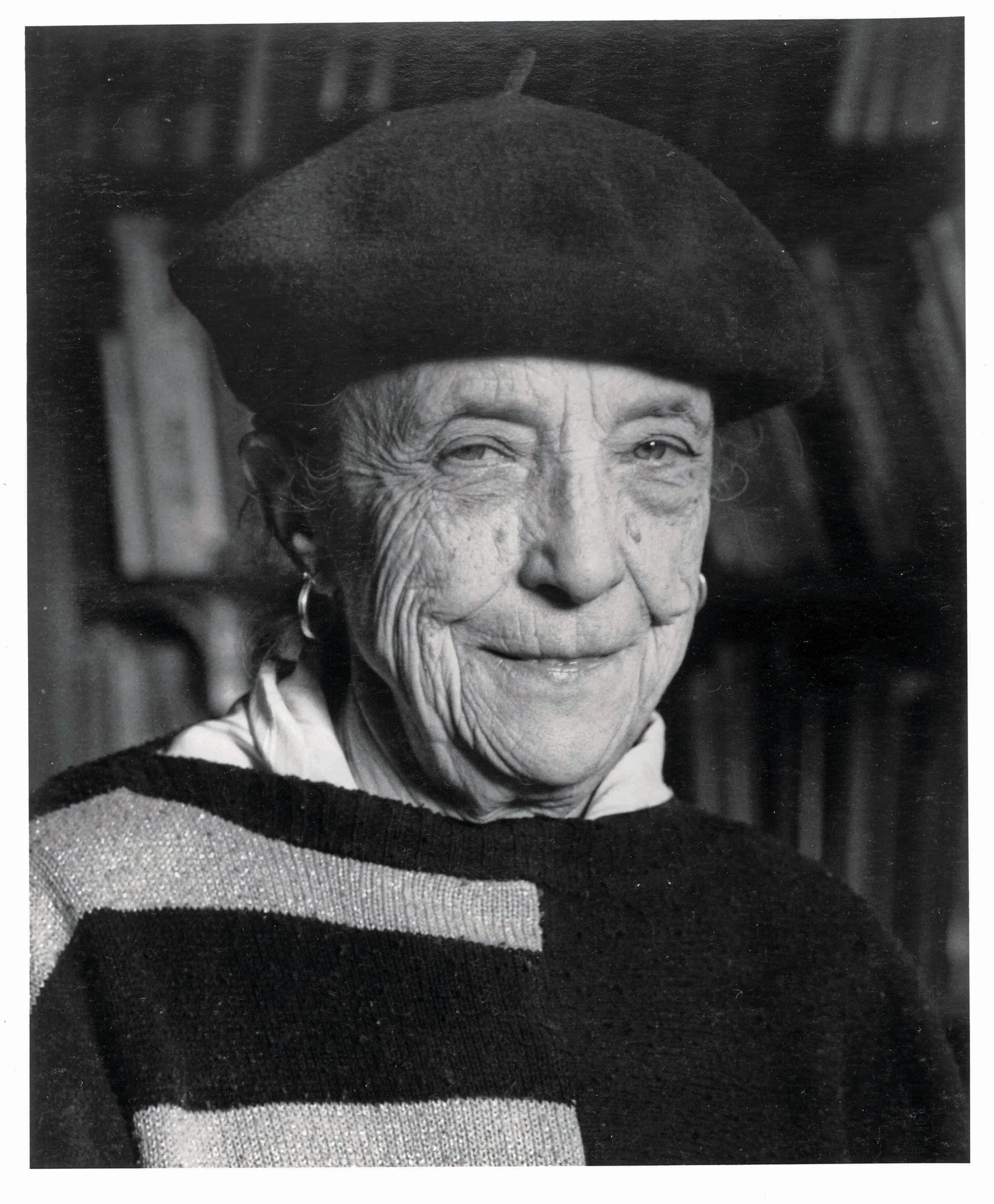

Shanghai authorities said that six works by Louise Bourgeois (above) could not be shown at the Long Museum. Photo: Chris Felver/Getty Images

What counts as a problematic work tends, loosely, to be anything explicitly sexually suggestive, some nudes, those with religious subject matter and politically engaged works that might be construed as criticising the Chinese regime. A foreign exhibitor at one of the fairs says anonymously that they were not allowed to bring a work that joked about global trade and Chinese manufacturing. Works by Georg Baselitz and Francis Bacon, proposed by international galleries were apparently among those turned down this year. Catalogues and books on a gallery’s stand also need to be approved and one gallery employee told us that videos, including the credits, must be translated into Chinese and sent to the authorities, “along with clips of around two minutes long from throughout the video”.

“You give a list of all the works you will be exhibiting, with descriptions, images and the backgrounds of the artists,” says Bao Yifeng, one of the co-founders of Art021, adding that the approvals process takes around three months. The fair also self-censors before the official process. “If we see a work that may have a problem, we will discuss with the gallery. Our fair is open to all ages, from children to adults, so we don’t want it to be full of nude images,” Bao says, adding that “every country has censorship, even America, but maybe not in black and white”.

Chinese galleries are not subject to this process but, Bao says, “the culture bureau also comes and does a tour of the fair. Sometimes we know they’re here, and sometimes we do not.”

Judgement is capricious and often depends on the official who deals with an application; in rejection letters, no explanation is given. So there are no hard-and-fast rules—indeed, some Shanghai-based commercial galleries were exhibiting comparatively provocative works at their galleries and in the fairs during the week. None would comment on the record, but some surmised that they were operating under the radar of the government.

However, at the Long Museum’s major survey exhibition of Louise Bourgeois, six works were censored. Among them was Labyrinthine Tower, described by the curator Philip Larratt-Smith as, “an abstract sculpture in bronze from 1962 that spirals in on itself” and Nature Study (1984) “a sculpture in blue rubber of the body of a dog with both multiple breasts and male genitalia”. Larratt-Smith says: “These works are sexually suggestive rather than sexually explicit.”

The artist list for the Shanghai Biennale was also only announced at the press preview in November, as project proposals had to be approved by the Culture Bureau before their production could start. “Most of the approvals came in late October, which was too late to have an announcement before the opening,” says the curator, Cuauhtémoc Medina. He describes the censorship process as “opaque” and around 20 of the 60 projects shown had to be resubmitted—some up to three times. Some had to be pixelated, such as a Francis Alys’s video, showing a dog mounting another dog. But a surprising number of overtly political works remain, and Medina says: “The Shanghai Biennale has a certain importance in determining what is possible in the art world in China… Some very radical works were not even touched.”