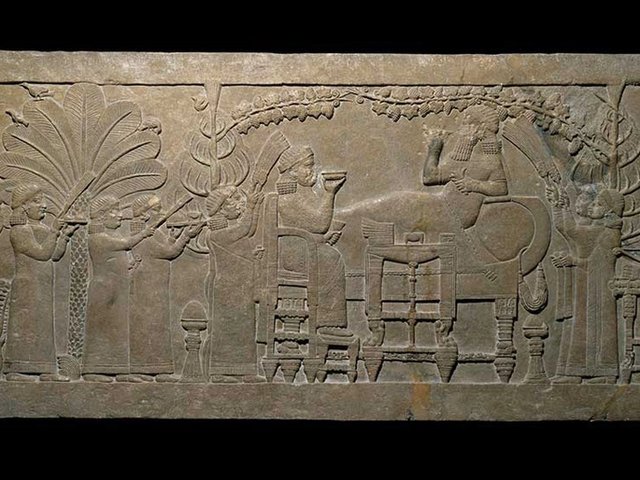

The British Museum’s hidden basement galleries are to remain closed under its new masterplan for a sweeping redisplay of its collections—but what treasures do they hold? Among the antiquities still being stored there is the Banquet Scene (645-635BC), the world’s finest single Assyrian relief sculpture, of the kind destroyed by Islamic State in Iraq.

The eight underground rooms were quietly shut to visitors more than a decade ago and have been widely forgotten. A museum spokeswoman tells The Art Newspaper that “there are no current plans to open up the basement galleries”.

These spaces housed two collections: Assyrian antiquities from present-day Iraq, and Greek and Roman sculptures. Built in the late 19th century, the galleries were originally double-height rooms. In the 1960s, they were cut in half to create a new floor at the main level of the museum.

In 2006, the basement was closed entirely, largely because of access problems. Without a lift, entry for disabled visitors was restricted. The museum was also concerned about evacuating visitors in an emergency. Keeping the galleries open required security warders, so their closure helped to save costs.

Two of the galleries contained Assyrian reliefs from Nineveh dating to the seventh century BC and recounting the story of King Ashurbanipal’s wars with the state of Elam. Some of these sculptures are still affixed to the walls, while others have been stored safely on wooden pallets on the floor.

Chief among them is the Banquet Scene, which we understand was recently valued at £100m, making it one of the most valuable objects in the British Museum’s collection. Unseen in London since 2006, it was lent to New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art in 2014-15.

The underground Assyrian galleries also presented other artefacts, including an eighth-century BC bronze bath from Ur, which was later reused as a coffin. It remains in storage there.

Many Assyrian reliefs will be leaving the basement temporarily for the major, BP-sponsored exhibition, I Am Ashurbanipal, which runs from 8 November to 24 February 2019. Others have been on loan in touring exhibitions. Most of the museum’s important Assyrian reliefs are, however, on continuous display on the main floor.

Six of the underground galleries were dedicated to ancient Greece and Rome, including architecture, classical inscriptions, early Ephesus material, Roman sculpture and Roman portraits. Larger Greek and Roman sculptures remain in the basement, where they can be viewed by appointment. Some objects have been moved to the main level or stored elsewhere. Others are included in the museum’s touring exhibition Rome: City and Empire, which is due to open at the National Museum of Australia in Canberra on 21 September.

The British Museum’s director, Hartwig Fischer, and its trustees are now developing a highly ambitious masterplan to reinstall most of the collection, a process that will take years and possibly decades. It is likely to be the museum’s most radical redisplay in more than 150 years.

Plans are still at an early stage, but the underground galleries will remain off-limits to the public and will probably be used for storage and handling of museum objects. Under the masterplan, the museum may decide to move some of the Assyrian reliefs from the basement up to the main floor.