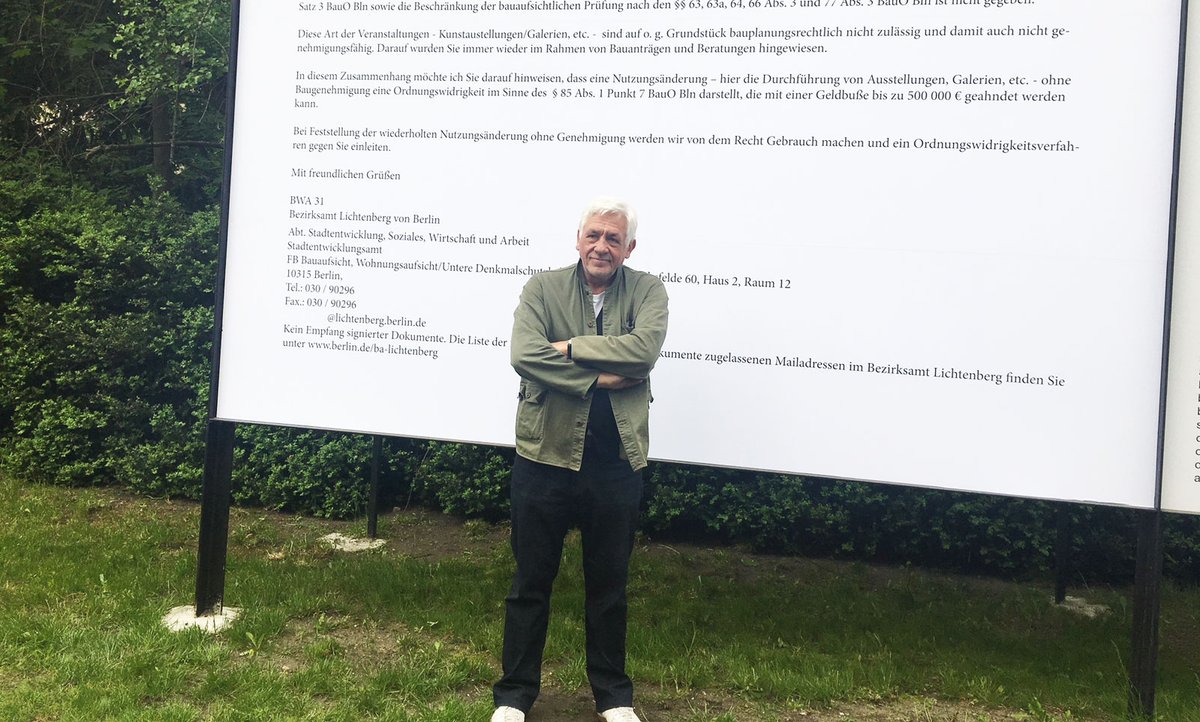

Axel Haubrok, an art collector and former management consultant, has pasted a giant copy of the email he received on 26 April from the local authority on a billboard at the entrance of Fahrbereitschaft, a complex occupied by tradespeople and artists in the district of Lichtenberg in an industrial corner of eastern Berlin.

“By hosting art exhibitions/ galleries on the premises of Herzbergstrasse 40-43, you are undertaking a modification of use that requires a permit. No permit has been granted,” it says. It goes on to warn that the maximum fine for violating local zoning laws is €500,000.

“This will be our last exhibition here,” Haubrok says as he gives a tour of the show, Paperwork, which includes works by Karin Sander and Barbara and Gabriele Schmidt Heins as well as pieces from his own collection by Stanley Brouwn, Martin Creed and others. The unwelcome email from the Lichtenberg district authorities landed just before Berlin Gallery Weekend (27-29 April), when about 500 guests made the five-kilometre trip from Alexanderplatz in the centre of the city to see the show.

The Fahrbereitschaft complex once housed the chauffeur service for top officials of the Socialist Unity Party, the ruling communist party of East Germany. It still boasts a vintage 1950s petrol station, a perfectly maintained GDR-era bar and a bowling alley. Haubrok purchased it five years ago and says he has since invested about €4m. Today it accommodates a dance workshop, artist studios, curators’ offices and a fashion designer as well as carpenters, a tyre fitter and a car spray painter.

“It’s a mixture of traditional industries and creative industries,” Haubrok says. “It’s like a village. The carpenters make frames and podiums for art and the car painter has recently started spraying sculptures. It’s very harmonious.”

But Fahrbereitschaft’s charming mix of the down-to-earth and the arty is also what has put it at odds with the Lichtenberg authorities. Birgit Monteiro, the deputy mayor of the district, sees it as her role to protect the industries in the neighbourhood—such as the scrapyard next to Fahrbereitschaft, the local newspaper printer and manufacturers like Pantrac GmbH, a maker of motor parts. “Some of these companies are in industries that have the lowest of profit margins,” Monteiro says. Because it is an industrial zone, such companies have fewer restrictions on noise and emissions and the rents are low, she says.

As rents in central parts of the city rise, artists have begun relocating to less desirable districts of Berlin in search of cheap space. Lichtenberg, as Haubrok says, “has the worst image of any district in Berlin.” Once home to the headquarters of the Stasi, the East German secret police, it subsequently became known as a haven for neo-Nazis.

Yet today, Herzbergstrasse is home to around 400 artists. “It’s the classic route to gentrification,” Monteiro says. “First the cultural world arrives, then the cultural world is pushed out by rising rents.”

For three years, the district authorities tolerated Haubrok’s exhibitions, but now Monteiro has cracked down—just as Haubrok was seeking support to build a new exhibition space to show his collection on the Fahrbereitschaft premises. While art production does not contravene the zoning restrictions, exhibitions are explicitly forbidden under Berlin Senate rules protecting industrial areas, Monteiro says.

“Berlin should help Mr. Haubrok find alternative space for his exhibitions,” Monteiro says.

But Haubrok is fighting back, and he has some powerful allies. To rally support for his planned new art gallery, he has organised a podium discussion at the Max Liebermann house by the Brandenburg Gate on 15 May. Among the speakers are Andreas Geisel, the Berlin interior senator, and Michael Grunst, the district mayor of Lichtenberg. Klaus Lederer, the Berlin culture senator, has criticised Monteiro and called for a solution, saying he supports Haubrok and Fahrbereitschaft.

“People have told me I should lodge an official appeal,” Haubrok says. “But I don’t think I should have to beg. We have brought a lot of people here and created about 100 jobs.”