The Salzburg Museum plans to return to Russia five grave reliefs and three amphorae shipped home during the Second World War by an Austrian army officer who took them as trophies from a war-damaged museum in the port of Temryuk on the Sea of Azov near the northeastern coast of the Black Sea.

Some of the objects date back 2,000 years or more to the Hellenistic period, when Greek settlements sprung up around the eastern Mediterranean and spread to the Black Sea. Russia’s President Vladimir Putin and the Austrian president Alexander van der Bellen agreed on the terms of their return to the Temryuk Historical Archaeological Museum during a May meeting in Sochi.

The officer was stationed in Temryuk with a Salzburg unit of the Austrian army. Museum staff had been aware for many decades that the objects were foreign to their collection. “As the Salzburg Museum, we are focused on art and cultural treasures from the Salzburg region,” says Martin Hochleitner, the director of the Salzburg Museum. “It was clear that these objects from the Hellenistic period didn’t belong in our collection.”

They were traced to the Temryuk Historical Archaeological Museum in the 1990s, but letters from Salzburg to Temryuk went unanswered, Hochleitner says. When the museum was preparing a 2018 exhibition on its history during the Nazi era, more detailed documentation about the provenance of the artefacts came to light, and the museum once again initiated restitution proceedings, this time via the Austrian Culture Forum and Austrian embassy in Russia.

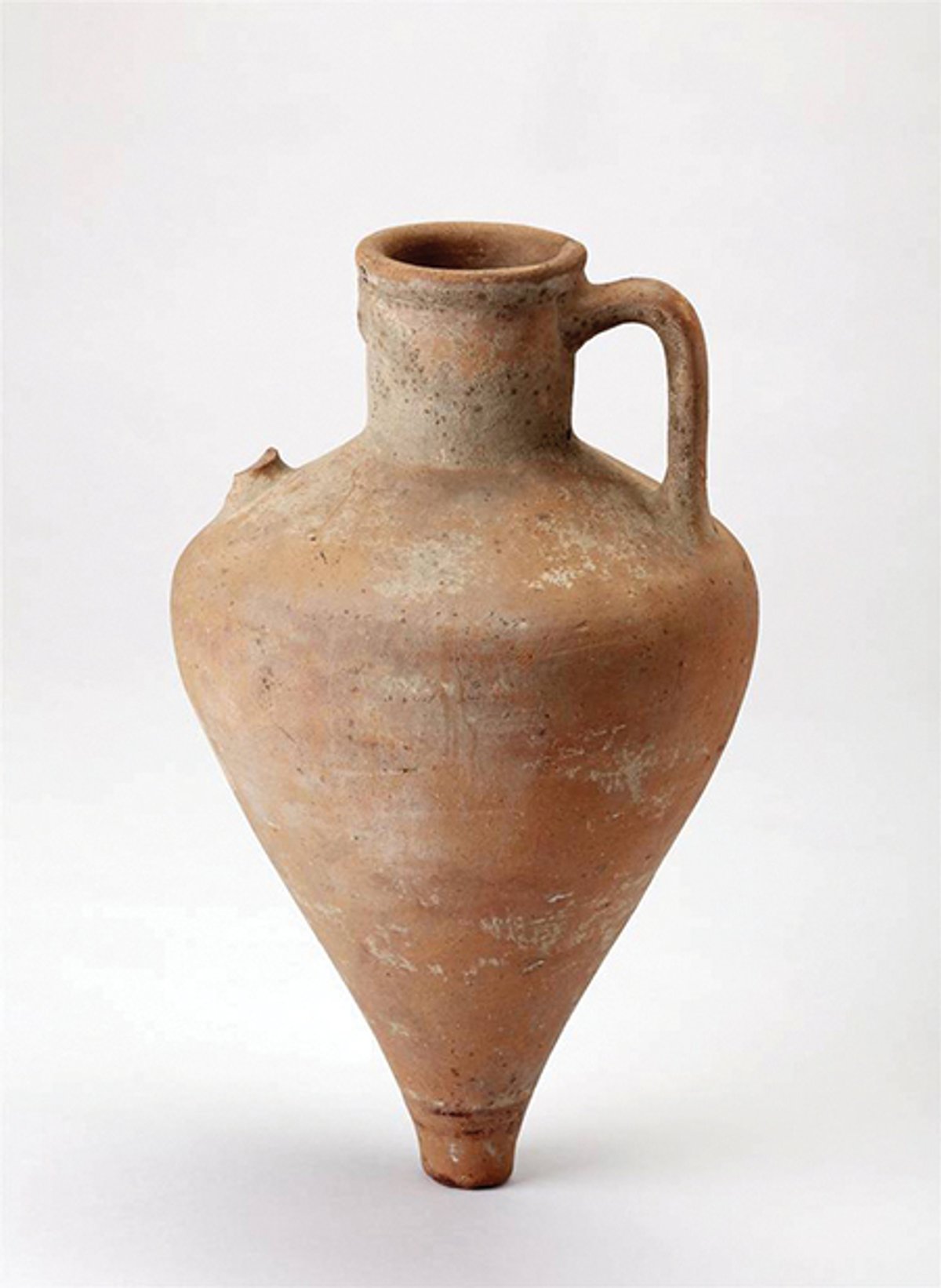

The amphorae and three fragments of reliefs that once adorned opulent graves in the easternmost reaches of Greek colonisation can be dated to between the fourth and first centuries BC. One shows a reclining couch typical of those used by Greeks to dine and relax. Another mixes local and Greek motifs, depicting a man mounted on a horse and bearing a lance wearing costume typical of the inhabitants of the steppe region. Two other reliefs reveal Roman influences and probably date from a later period.

Restitutions to Russia from western European museums are a one-way street: Russia itself does not return cultural property seized by the Soviet Union’s trophy commissions from Germany at the end of the Second World War. In 1996, the Russian parliament passed a law nationalising the spoils of war, which it saw as reparations for Russian heritage losses at the hands of German troops.

Hochleitner says Russian policy is not relevant to the Salzburg Museum. “We are not giving back in order to have things given back to us,” he says. “We want to right a past wrong.”

The Salzburg Museum, which was itself destroyed in 1944, has recovered several items plundered by US troops at the end of the war, including 94 rare, historic coins returned by the American Numismatic Society in 2017.

A ceremony for the handover of the eight Russian artefacts is expected in the coming months, though planning is currently on hold because of the collapse of the Austrian government and elections scheduled for September, Hochleitner says.