The controversial art and antiquities dealer Forrest Fenn—best-known for hiding a $2m treasure chest in the Rocky Mountains—has died, aged 90, just months after his infamous treasure was reportedly found.

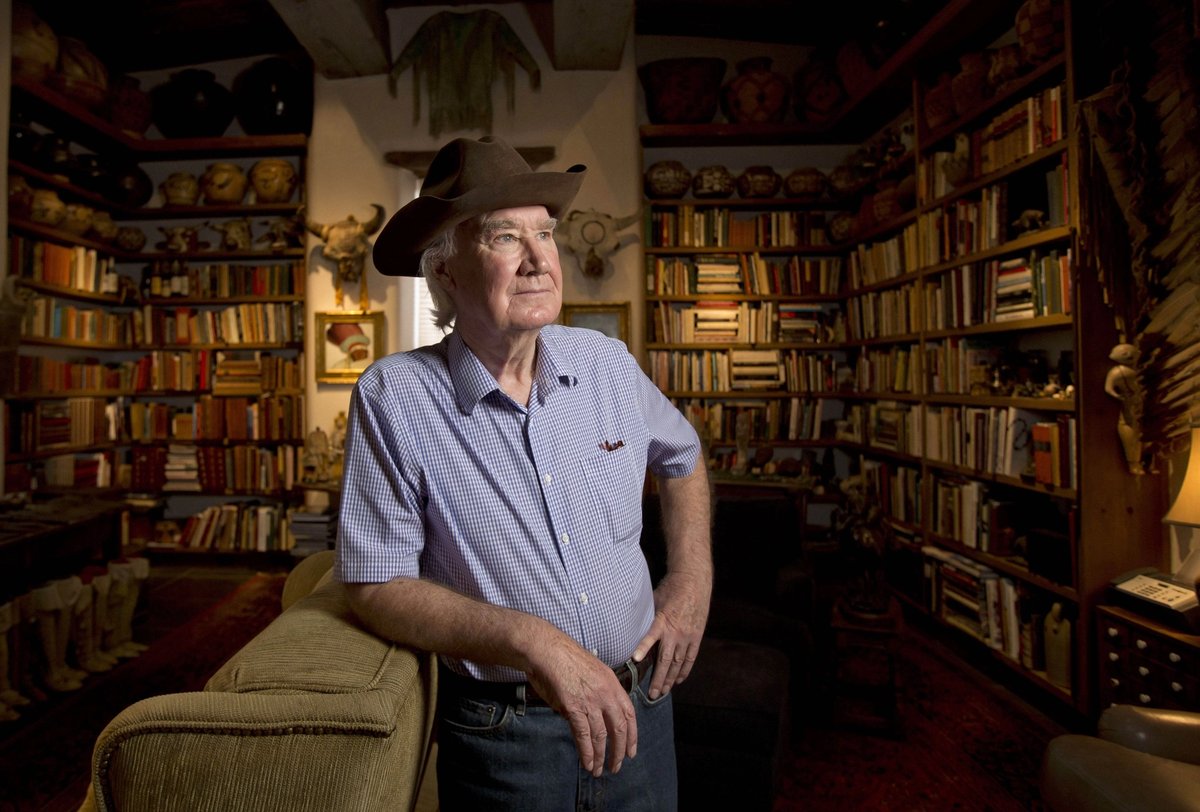

Fenn was born in Temple, Texas, in 1930, and moved to Santa Fe, New Mexico, in 1972, where he would spend the rest of his life and career. A so-called “Renaissance Man”, Fenn led a colourful life that included serving as a fighter pilot in the US Airforce during the Vietnam War, excavating and collecting artefacts from around the world, and authoring books with subjects ranging from war to archaeology and art.

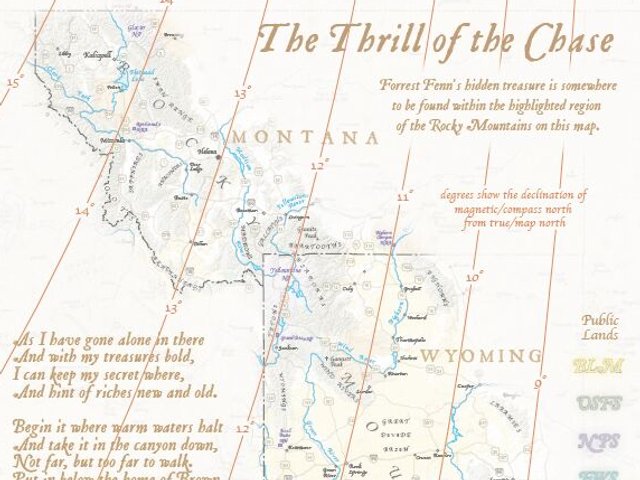

It was in his 2010 memoir, The Thrill of the Chase, that Fenn wrote a six-stanza poem of the same name that contained a set of nine clues; these hints, he said, would lead to a treasure chest of gold nuggets, gems and pre-Columbian and Chinese artefacts that he had hidden in the Rocky mountains. The contents of the chest were estimated to be worth between $1m-$2m. Around 350,000 people are known to have hunted for the bounty, by Fenn’s account, and authorities say at least four died in their search.

The stunt was long-thought to be a hoax but, just months before his death, Fenn announced that the treasure had been found by an individual who wished to remain anonymous, and that it had remained “under a canopy of stars in the lush, forested vegetation of the Rocky Mountains and had not moved” for ten years.

Fenn added that he hid the treasure as a morale booster amid the 2008 economic crash and to encourage others to enjoy the outdoors. He felt “halfway kind of glad, halfway kind of sad” when the treasure was found “because the chase is over”, but said he hoped people would “continue to be drawn by the promise of other discoveries”.

The search for his treasure yielded numerous TV news shows, newspaper and magazine articles and documentary films. The search also spawned an annual gathering of campers at Hyde Memorial State Park known as Fennboree.

While he was celebrated for his charm and pithy anecdotes on life, Fenn’s career as an art and antiquities dealer was also peppered with controversies, many of which he fervently argued against in his memoir. In the 1970s, he was lambasted for selling oil paintings by the Hungarian artist Elmyr de Hory, a known forger of Impressionist works. Despite claiming to have disclosed the works as fakes, Fenn rebuked his critics by saying that if someone liked a painting less “just because it’s fake, who is the fraud now?”

The dealer was also scrutinised for purchasing pueblo ruins in the Galisteo Basin in Santa Fe and opening the site to amateur excavators during the 1980s. Additionally, in 2009, federal agents raided Fenn’s home as part of a string operation investigating the illicit trade of Indigenous artefacts.

Although Fenn was never charged with any crime and told officers he excavated artefacts from his own property, the informant involved in the operation recorded the dealer explaining that he flew over the remote Southwestern desert while in the military to search for ruins. “And then on the weekends we’d go in there,” Fenn is recorded saying. “We found so many caves that, evidently, nobody had been in since the Indians.”

Tim Maxwell, the former director of the New Mexico Office of Archeological Studies, told the Santa Fe New Mexican on Tuesday that “Forrest forged ongoing associations with some in the archaeological community but had a tense relationship with many others,” noting that there were worries that he was excavating San Lazaro for commercial purposes.

Maxwell adds: “Forrest said he would never sell objects found at San Lazaro, and he added a room onto his home to store and study the artefacts. As far as I know, every artefact is still there. He also purchased exceptional private collections and allowed scholars to study them.”

Santa Fe police confirmed the dealer and collector died of natural causes. He is survived by his wife and two daughters.