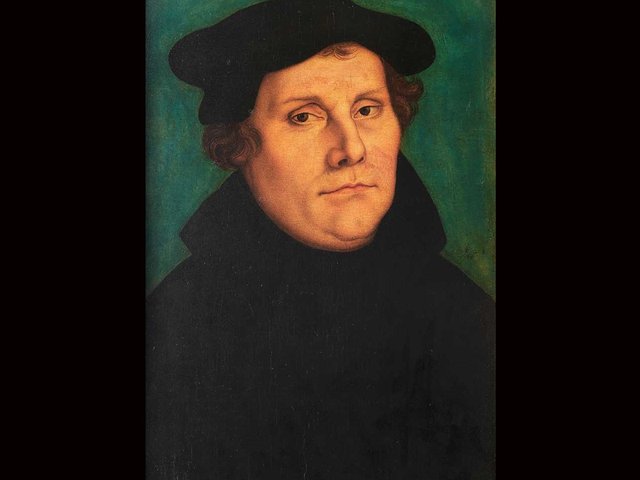

Church leaders and art historians are debating whether to remove an obscene 13th-century anti-Jewish relief from the façade of the heritage-protected church where Martin Luther once preached in the German city of Wittenberg.

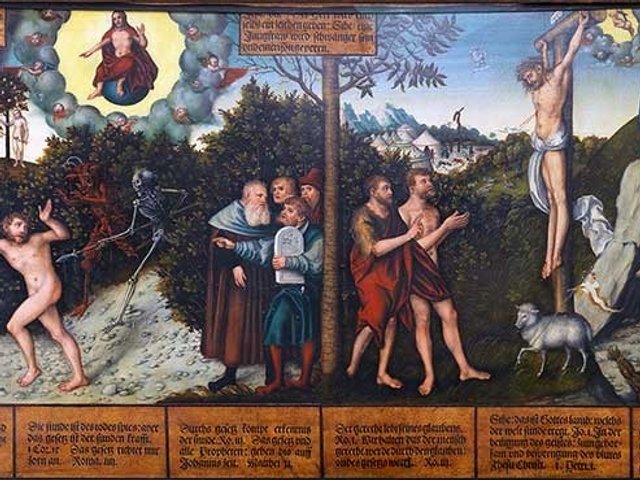

The sandstone relief depicts Jewish people drinking from a sow’s teats while a rabbi lifts her tail to inspect her hindquarters. In response to a court complaint filed by a member of the German Jewish community and an online petition, the Evangelical Church is now discussing its removal and alternative display options.

“The proposal to take down the medieval sculpture and integrate it into a new monument seems convincing to me,” Irmgard Schwaetzer, the president of the synod of the Evangelical Church in Germany, said in a statement sent by email. “It expresses pure hatred of Jews. A centre of education that finds acceptance beyond the parish should be established here. This also means considering the feelings that this place awakens in our Jewish brothers and sisters.”

Around 30 “Judensau” (Jewish Sow) images still exist in medieval churches around Europe, primarily in Germany. The oldest surviving example, dating from 1230, is in Brandenburg. Their intention was to dehumanise Jewish people, provoking scorn and ridicule by associating them with a beast considered impure and dirty.

Until now, the church has shown no willingness to consider the removal of the Wittenberg relief, says Richard Harvey, a British theologian specialised in Jewish-Christian relations and the author of an online petition which has garnered 10,000 signatures advocating its relocation. Heritage experts have also argued against taking it down.

“We can’t allow this to lead to a kind of iconoclasm,” the art historian Insa-Christiane Hennen said in an interview with Deutschlandfunk radio station. “The problem of modern-day anti-Semitism cannot be solved by removing these medieval objects.”

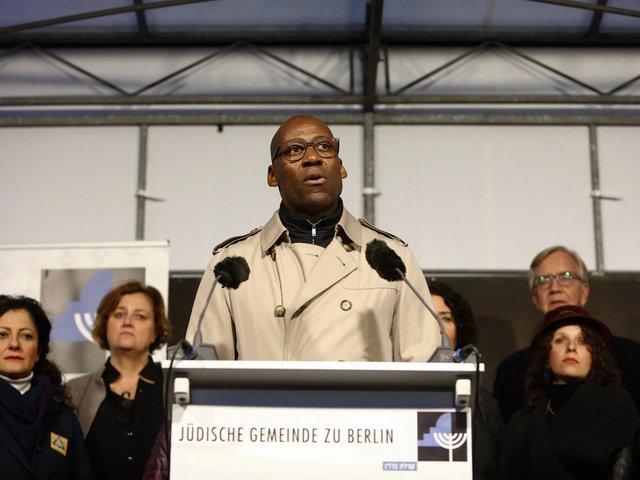

A legal complaint demanding the removal of the Wittenberg relief filed by Michael Düllmann was rejected by a regional court on 24 May. Düllmann had argued that the church was abusing and insulting him and other Jews. The court ruled that the fact that the church had not removed the relief could not be considered abuse.

“We have lost the first round,” says Hubertus Benecke, the lawyer representing him. “My client plans to appeal. We will also be watching to see how the discussions develop.”

Harvey says the Wittenberg relief is “the most egregious example” of a “Judensau” because it is located on the façade of the church in full public view. It is also in the church where Luther preached and married—a Unesco World Heritage site. A post-Reformation script on the image echoes an anti-Jewish text by Luther, implying that the Rabbi inspecting the sow’s behind is trying to read the Talmud. The parish added a plaque and an explanation in 1988, when Wittenberg was still behind the Iron Curtain.

“I have tremendous respect for what they were trying to do,” Harvey says. “But these days, more needs to be done. The sculpture continues to cause offence and defame Jewish people and their faith. I want it to be relocated to a museum or study centre so it’s removed from sacred space and from public social space.”