It is not often that a work of art sells at auction for a price that creates a sense of wider significance—and outrage. But two days after Sotheby’s sold Banksy’s Devolved Parliament for £9.9m (including fees) on 3 October, the renowned curator Francesco Bonami, a consultant to the Phillips auction house, lambasted the artist in an article in the Italian newspaper la Repubblica.

“The €11.1m spent on the canvas of the mysterious king of graffiti marks the birth of a collection inspired more by social networks than by art history,” Bonami lamented. “If Faust sold his soul in exchange for wisdom, the art world, more prosaically, sold both its soul and its wisdom for profit.” The article concludes by dubbing Banksy and KAWS, aka Brian Donnelly (whose cartoon-inspired paintings and sculptures have also achieved formidable auction prices recently), “the nothings that threaten everything”.

But what, exactly, is the “everything” threatened by Banksy and KAWS?

Banksy’s Devolved Parliament sold for £9.9m © Bristol Culture

In terms of the market, Sotheby’s, Christie’s and Phillips can do with all the “nothings” they can get. This year’s otherwise lacklustre Frieze Week evening auctions raised £121m between them—almost 18% down on the previous October, according to the London-based analytics company ArtTactic.

With owners currently unwilling to risk selling museum-quality works at auction, and dealers trying their best to stop speculators “flipping” pieces by younger, in-demand names, street art has become one of the few areas of genuine growth for the auction houses.

Instagram celebrities

In April, KAWS’s Simpsons and Sergeant Pepper-inspired 2005 painting, The Kaws Album, sold for an astonishing $14.7m at Sotheby’s in Hong Kong. A 2015 KAWS painting, The Final Machine, topped up Sotheby’s Frieze Week sale with a hefty £615,000. KAWS has 2.5m followers on Instagram while Banksy has 6.6m. Gerhard Richter, regarded by many as the world’s greatest living artist, has just 48,000.

As far as the wider world is concerned, was Banksy’s prank-performance in Venice in May (4.1m Instagram views)—in which he set out a stall of kitsch tourist canvases that turned into a polyptych of a huge cruise ship in the Grand Canal—saying so much less than paintings by “somethings” such as Julie Mehretu and George Condo at the nearby Biennale?

Consumer collectors aren’t at the cocktail parties, but they want to be part of art worldMaeve Doyle

“Popularity is the key. We can’t fight it. It’s a fact of life,” says Alain Servais, a Brussels-based collector. “The elitist art world doesn’t know how to handle this reality.” For Servais, the appearance of that Banksy painting at Sotheby’s was a welcome relief from the predictability of the art at Frieze London and other international fairs. “You go round Frieze, and everyone is wealthy and happy with the situation,” he says. “Why do we have to see the same stuff all the time? I’d far rather have a Banksy than a Peter Doig. I’ve always considered Banksy an important artist. He has a way of turning things upside down.”

Banksy is just one example of the way in which the received wisdom of the art world is being threatened from below, as populism snaps at the heels of criticism.

Consumer collectors

In January, at the Talking Galleries symposium in Barcelona, Joe Kennedy, the co-founder of the London-based Unit London gallery (460,000 Instagram followers), identified a new breed of social media-aware “consumer collector”, who has money, but not enough time to navigate the intimidating opacities of the “serious” contemporary gallery scene.

Rather than be told “nothing is available” and join lengthy waiting lists, these clients are drawn to the more commercial, consumer-friendly galleries now proliferating in London, Paris, Los Angeles and other major cities.

“Changing cultural values are informing and changing the way we go about our business,” Kennedy says. “Popularity has real currency in the day we’re living in.”

The works of art on show at galleries like Unit, Hang-Up or Maddox (to pick three representative examples in London) may not be the stuff of biennials, but, like it or not, colourful, instantly gettable images laced with references to popular culture are what today’s consumer collectors want.

“They’re people who don’t have the swagger, who aren’t on the red carpet or at cocktail parties, but who still want to be part of the art world,” says Maeve Doyle, the artistic director at Maddox Gallery, of its clientele.

Maddox Gallery shows of the Connor Brothers’ paintings instantly sell out Image courtesy of Maddox Gallery

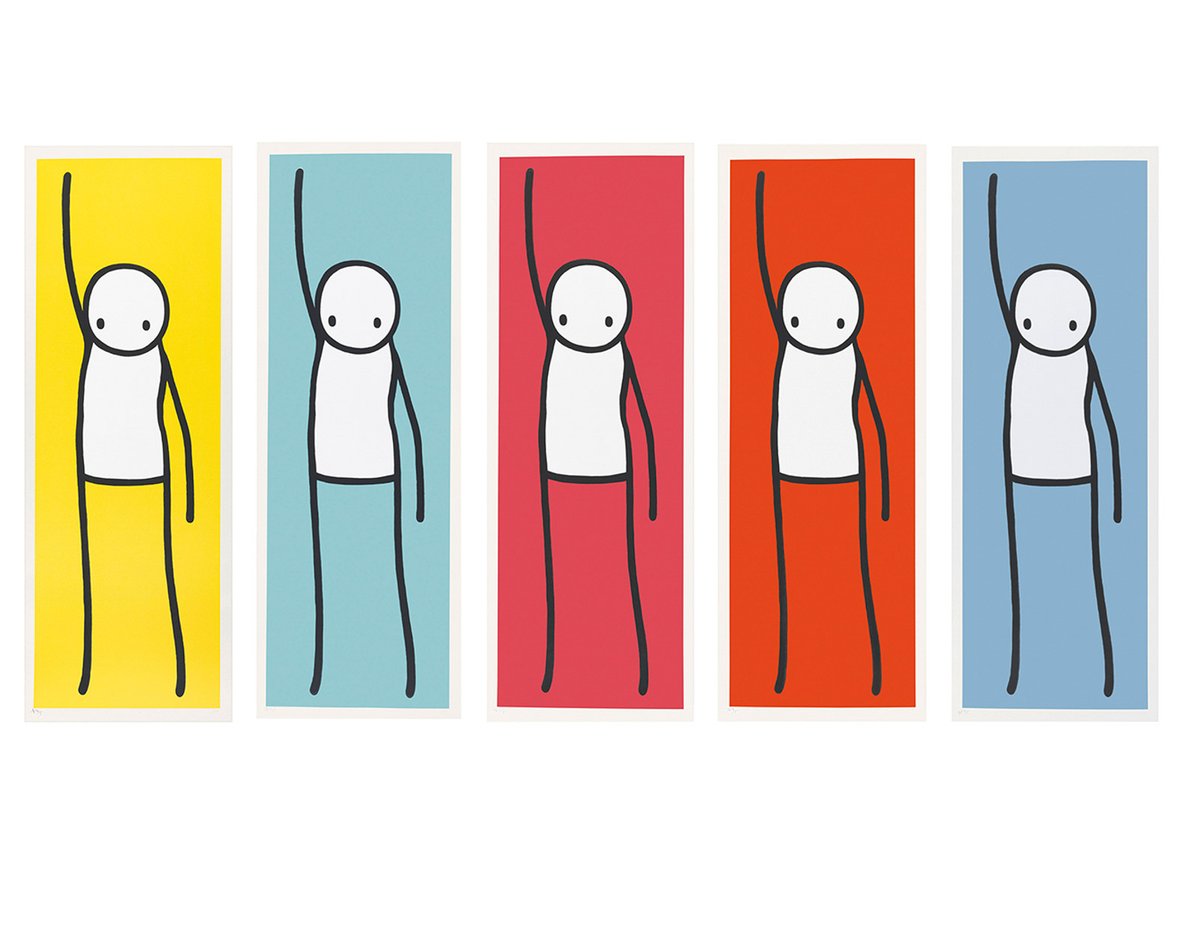

This is why the Waddingtons board game-inspired Los Angeles street artist Alec Monopoly was the seventh most-searched artist on the Artnet database in 2018; why Maddox Gallery shows of the London-based Connor Brothers’ paintings of mordantly retitled pulp fiction covers instantly sell out (one painting was flipped for $45,000 on 7 October at Sotheby’s, Hong Kong); and why a deluxe set of five Liberty screenprints by the British street artist Stik, based on the mural he painted in New York in 2013, sold for £200,000 at a Christie’s print sale on 18 September.

Contemporary art’s cognoscenti may regard all this stuff as something of a joke. But the £9.9m achieved by Banksy’s Devolved Parliament now looks a truly prophetic visual gag: Britain’s political establishment failed to take populism seriously, and it has made monkeys of them all. The art establishment should watch out.