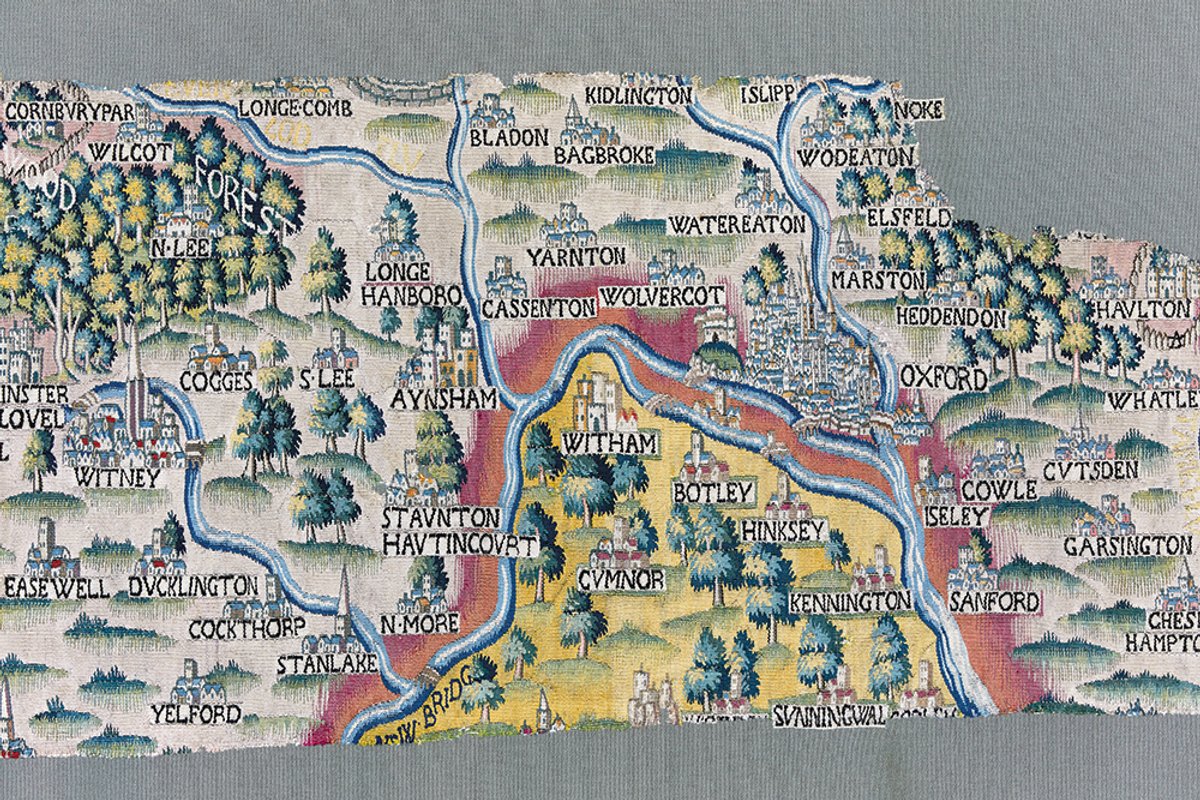

There is no village called Easewell in north Oxfordshire, although it is clearly shown as a delightful place with a parish church surrounded by fields on a unique map that has just gone on display in the Bodleian Library in Oxford—probably for the first time in 400 years.

The mythical village is just one of many mysteries surrounding a set of huge tapestry maps of English Midland counties, woven in silk and wool at fabulous expense around 1590 for a rich man called Ralph Sheldon. His own house in Warwickshire was originally shown, bristling with chimneys and the size of a small town, on each of the four maps though it only survives on one.

The mysteries include who made the maps and where, and how such sumptuous and rare objects disappeared from history. They should have been famous, dazzling Sheldon’s guests when few would have seen a map of any kind, but researchers have found no references to them from the period.

Nick Millea, head of the library’s huge maps collection, knows there is no Easewell because he lives nearby; other maps show a moated farm called Caswell, so he wonders if the tapestry is a Tudor typo. He has found little to explain what happened to the maps in the centuries between Sheldon’s death in the early 17th century and the gift to the Bodleian of the Oxfordshire and Worcestershire tapestries in the early 19th century. In 2007, the library managed to acquire the biggest surviving chunk of Gloucestershire when it came on the market with an equally vague provenance. The Victoria and Albert Museum in London owns a few more fragments that the Bodleian hopes one day to reunite on display, while Warwickshire county council owns that map.

Damage from creasing suggests that the tapestries were folded for long periods, says Virginia Lladó-Buisan, the Bodleian’s head of conservation. And straight-edged gaps show where sections were deliberately cut out to use in upholstery—a chunk of Gloucestershire reportedly ended up as a fire screen.

"Gentle washing in Belgium brought out astonishingly beautiful colours"

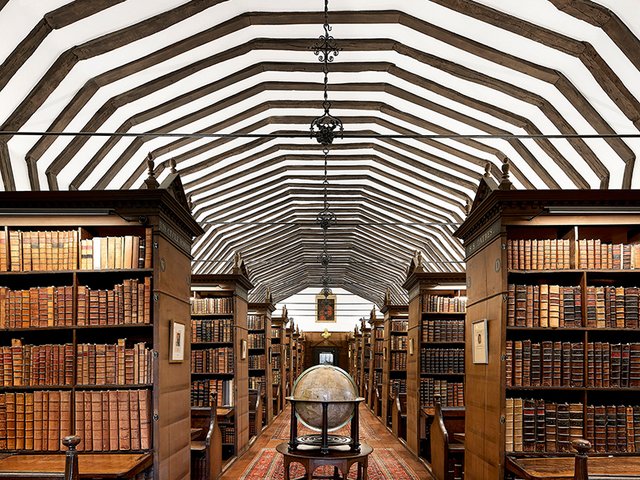

For 200 years the Bodleian never displayed any of the tapestry maps because it never had a big enough spare wall. The three finally came out of storage when the Weston Library building opened in 2015, creating the first proper exhibition space for one of them. All three have been magnificently restored in partnership with the National Trust’s conservation experts. Gentle washing in Belgium brought out astonishingly beautiful colours, suggesting they could never have been exposed to daylight for long. Delicate repairs at the trust’s Norfolk workshops included hand stitching on to a new backing, patching back in identifiable fragments and restoring some damaged place names. An international research project on the origin of the dyes, in partnership with the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the National Museum of Scotland, is due to report this autumn.

Worcestershire, which went on view in 2015, now sits in a deep freeze just in case it picked up any unwanted insect visitors during its four years on display. Oxfordshire has replaced it and members of the maps department will give a free talk in front of it every weekday morning. There is plenty to say: though damaged, it includes a magnificent beast representing the figure that is cut into the turf in the Vale of the White Horse and London is shown with the Tower of London, a solitary bridge and the tall spire of Old St Paul’s 70 years before its destruction in the Great Fire. Oxford itself is praised in a florid text panel for its “sixeteene colledges and eyght halles”. The fragment of Gloucestershire, meanwhile, features in a major free exhibition on maps opening at the Bodleian on 5 July.

Millea and Lladó-Buisan wonder if they should knock on the doors of all the grand country houses in their region and ask if by any chance they have an old cushion cover densely woven with villages, church towers, orchards and deer parks—and non-existent villages.

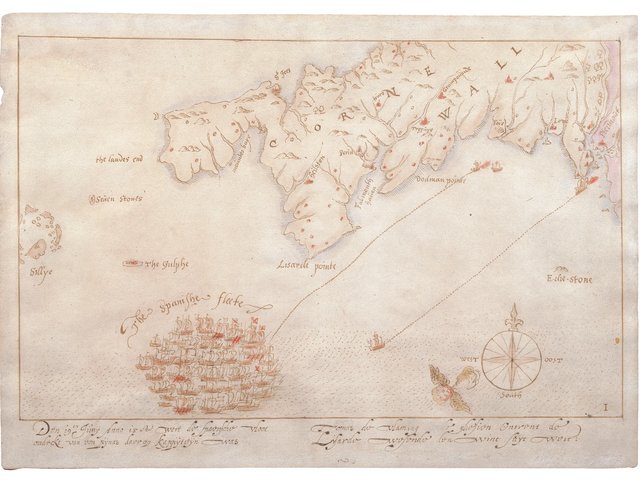

Talking Maps, until 8 March 2020, Weston Library, Bodleian Libraries, Oxford