The travelling exhibition, Susan Meiselas: Mediations, surveys the work of the American photographer (b. 1948), known internationally for her on-the-ground documentation of life in conflict zones. Behind her widely seen records of liberation movements in Central America, of the besieged in Kurdistan and other communities in jeopardy, lie more intimate and less celebrated engagements with the teenage denizens of her Manhattan neighbourhood, carnival strippers and, most recently, female victims of domestic violence.

Throughout her career, as the exhibition and its catalogue attempt to demonstrate, Meiselas has interrogated the evidentiary value of pictures and the many impingements on their reception.

The retrospective was co-organised by the Fundacio Antoni Tapies in Barcelona, where it opened last year, and the Jeu de Paume, Paris, where it continues through 20 May. It comes to the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, its sole American venue, on 21 July. We spoke with Meiselas at her home in New York.

The Art Newspaper: Was there an experience in your life that sensitised you to issues of injustice?

Susan Meiselas: I've been thinking a lot about that coincidentally because I was last week in Montgomery, Alabama, where they just opened a memorial to victims of lynching. It's a stunningly simple, elegant, deeply researched and painful sort of register. And I've been revisiting a certain period of my life. My mother was from southern Virginia, a very rural area, and though she married my father, who was from New York, and moved north... the South was part of my early exposure to life. It wasn't the deep South, but a set of values was transmitted by her, without anger, a sense of purpose in response to the disparity of cultures.

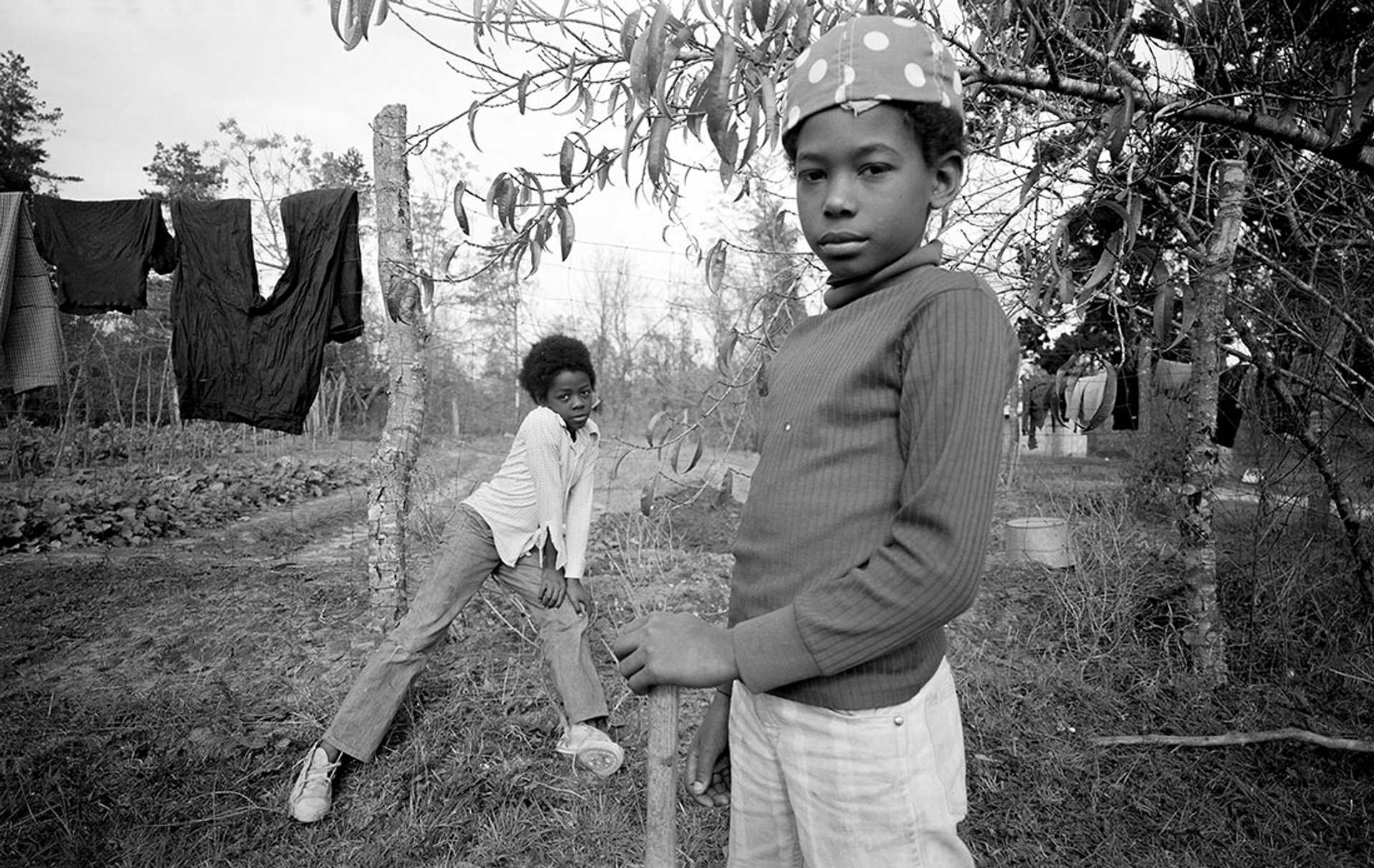

Mississippi, USA, 1974 Susan Meiselas/Magnum Photos

And living on the fringe of New York, being exposed to a popular culture that made no sense. My uncle was the manager of the Stable Gallery in Manhattan, when Warhol showed his Brillo boxes and Campbell's Soup cans. I met a number of other artists who were very passionate about being artists. I remember Marisol well, for example. But I didn't identify as wanting to be an artist. I still don't, really—I just do what I do.

Finding my medium took time. Teaching photography to kids in public schools was really important, but I didn't know at that time that I was choosing a way of entering the world. I do identify within the documentary tradition, but I've never been directed by what other people want as much as by where I want to go, where I want to stay, where I want to go back to, what's still dwelling within me that's unresolved that I need to think about.

Do you see exhibitions as devices to shape your work's meaning and reception?

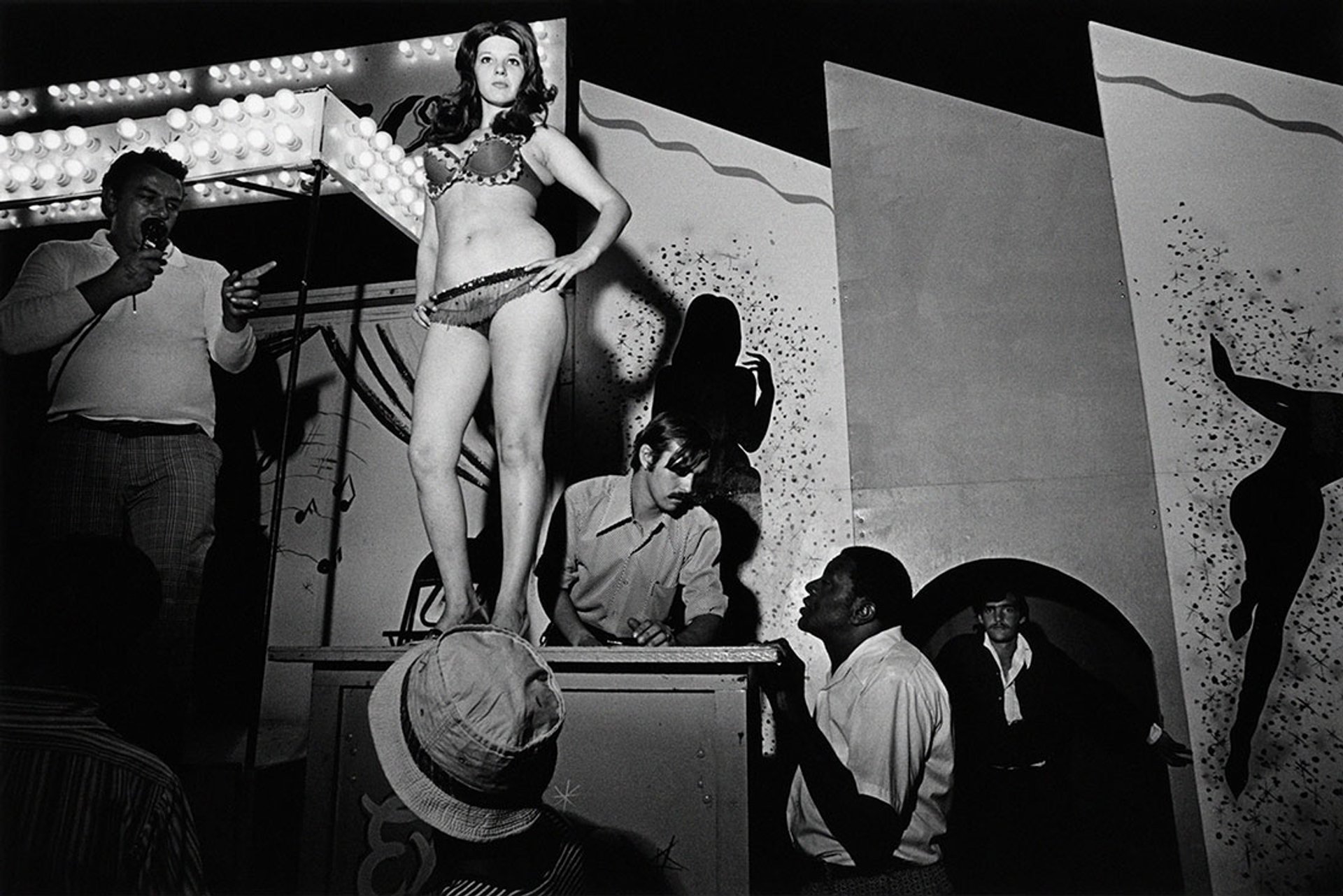

Totally. First, I saw books as the opportunity to shape response. Carnival Strippers had a sound element, but when the Nicaragua book was done, all the sound was transcribed. It's really various kinds of voices in the back of the book. I didn't want just pictures strewn through magazines. I wanted to bring them together, create a home for them, a bi-cultural object.

Widow at mass grave found in Koreme, Northern Iraq, June 1992 Susan Meiselas/Magnum Photos

When I did the Kurdistan book, the show became the important element, because it travelled where the Kurdish minorities lived around Europe at a time when you couldn't get to Kurdistan. It was completely closed off by war or Saddam Hussein's control. So moving the exhibition through Germany and Holland and France became a forum for exchange. That's when museums interest me... The Jeu de Paume has been fabulous that way. I did a workshop a week before the opening with Kurds from all different parts of France. I've always thought of exhibitions as meeting points to bring different audiences together. It's different with a book, where you have a private experience, sitting in your home.

What's the most gratifying form of reception you've received?

At one point, the cover of a magazine was an incredibly important moment, because suddenly I was revealing to people what I was doing, whereas before it was just me doing it. That had an impact on me, a sense of responsibility as regards representing what I saw, for example in Nicaragua, because I was the eyes in the field. We don't feel that the way we did then. In the late 1970s and early 80s in El Salvador, I felt a huge burden of responsibility—how can I help people understand what's happening here?

Sandinistas at the walls of the Esteli National Guard headquarters, Nicaragua, 1979 Susan Meiselas/Magnum Photos

Some e-mails people have written, who've taken the time to be with the work privately, are very moving to me. The counterpoint is to be in the exhibition space when nobody knows it's me, and just see people relating in whatever ways they do. I've said to a few people jokingly: "I think I should move to Paris. They understand me there." Barcelona was hard because [the show] opened on the night that the Basques declared autonomy, and it led to a lot of tensions in the street. But in Paris, it's had tremendous response from the press, people from different political frameworks, across the spectrum of journalism and art. It doesn't get much better than that.

Do you think people care any more whether they can believe what they see in images?

We used to talk about “compassion fatigue”, and I avoid social media because it's a challenge to stay sensitised, so I can feel what I feel and act upon it when it feels right to do so... When I reissued the Nicaragua book about 30 years later through Aperture, I had made the feature-length film Pictures from a Revolution, and we put the DVD in the back of the book. And I loved the idea that this fixed linear object could have this extension of time embedded in it.

When Aperture wanted to publish a third edition of the book, they said we can't do a DVD because nobody uses them anymore. You don't anticipate technology changing that fast. So this time, I customised with a developer team something called a Look and Listen app, which allows you to hold your iPhone over a certain picture and that triggers the corresponding sound clip from the film, so you can hear the voices of people in the pictures. It appeals to a certain kind of temperament that we now have—nobody wants to watch a 90-minute movie, but a 2-to-4-minute clip is just about where the attention span is.

Lena on the Bally Box, Essex Junction, Vermont, USA, 1973 Susan Meiselas/Magnum Photos

Does your place in the art economy affect your thinking about content or interpretive context?

I didn't make an edition until 1995 because I come from the Cartier-Bresson generation that thought: just make pictures for reproduction, because that's what this medium can do. I wasn't in the market... I lived in a very fluid economic ecology, where independence was key to its functioning. I didn't need someone to pay me to go somewhere and work. I'd just be there and the work on the back end would live in an environment that was paid for. That barely exists any more... A lot of my effort recently has been building the Magnum Foundation to sustain the possibility for the next generation, which I think is not a small thing.

What about your preference in cameras?

I love changing cameras, I love experiencing myself with different cameras. Something about a format shift moves your eye differently. The Hasselblad is a very still, perfectly aligned, flat horizon view. With a panoramic camera, when you move, it moves, so you get a very different relationship to a subject in motion. It was perfect for a particular process and project, but I haven't used it since... The Leica was perfect for Carnival Strippers, but not for me now. Digitally, I have tended to work with one camera—the Canon. Digital is phenomenal for the quality it can give you, but it's a heavy camera... Between a Hasselblad and Rollei, there might not have been a significant difference, because they were both square, good for portraiture, where for reportage, a 35 felt right.

I'm not talking lenses—that's another whole subject. Inevitably, someone will ask me after a talk: "What lens do you use?" To which I recently answered: "It's not what lens you use, it's what lens you think you are."

Portrait of Susan Meiselas, Monimbo, Nicaragua, September 1978 Alain Dejean Sygma