Four months after the grand inauguration of Louvre Abu Dhabi, Jean-Luc Martinez was off to Iran in March to open The Louvre in Tehran—a temporary exhibition (until 3 June). Unlike most art historians, the director of the Musée du Louvre in Paris, whose mandate was renewed for three years last week by the French president, Emmanuel Macron, does not shy away from political commitment and fully embraces the diplomatic role played by his institution.

“The Louvre’s operations overseas contribute to France’s international outreach and, yes, the museum must take into account the government’s priorities and foreign policies,” he told The Art Newspaper in Tehran. The packed opening of its show of 56 artefacts at the National Museum of Iran, which was attended by the French foreign minister, Jean-Yves Le Drian, is a case in point. The Tehran Times hailed it as “a diplomatic triumph”, although the minister made little headway on issues such as Iran’s ballistic missile programme.

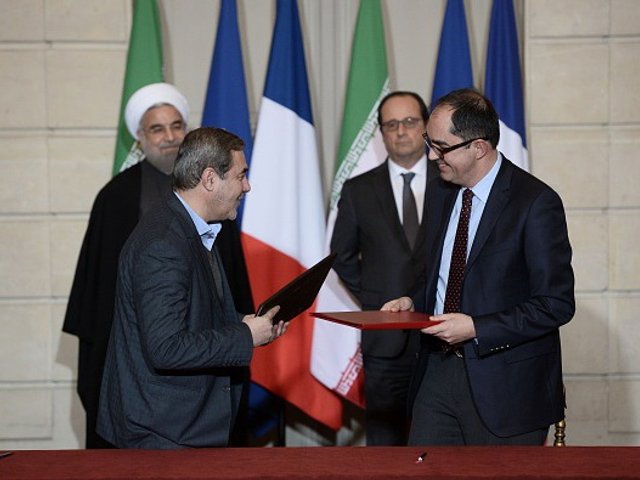

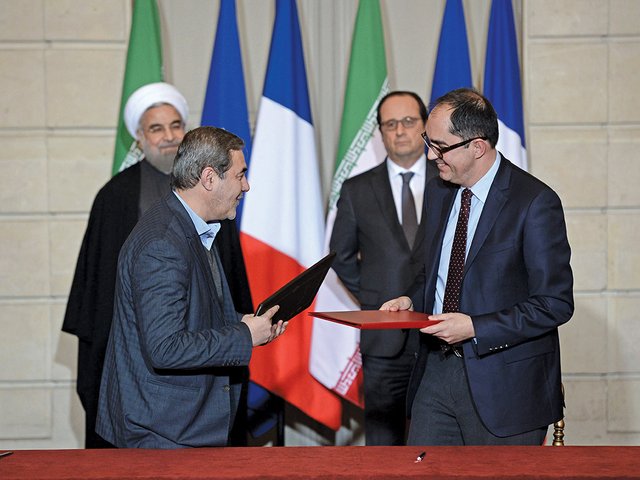

Martinez laid the groundwork for the collaboration with the National Museum, which was designed in the 1930s by a French architect, even before sanctions on Iran were lifted in 2016. He signed an agreement with the Iran Cultural Heritage, Handicrafts and Tourism Organisation in 2015. This paved the way for an archaeological dig on the Silk Road and an unprecedented loan of regalia by the Royal Palace to an exhibition on the Persian Qajar dynasty, which opened last month at the Louvre-Lens in northern France.

Taste for soft power

When he was appointed in 2013, Martinez said his priority was to improve visitor conditions at the Louvre in Paris, the world’s most popular museum. But the success of Louvre Abu Dhabi—a project initiated by his predecessor, Henri Loyrette, which was then on the brink of collapse—is testament to his growing skill and taste for cultural diplomacy. Further encouragement has come with the presidency of Macron, who held his election victory rally in the museum’s courtyard last May.

“The Louvre is more active than ever internationally,” says Martinez, citing collaborations in 75 countries. Since 2013, the museum has co-organised 49 exhibitions in 17 nations, including the United States, China and Japan. Almost a quarter of its eight million visitors come from these three countries and Japan contributes 10% of its sponsorship. “This is part of our outreach towards our own audience,” he says.

But the museum also stages exhibitions in less likely places, such as Sudan next year, Martinez says. This will focus on Taharqa, the Kushite pharaoh who ruled Egypt 3,000 years ago. “Such a show, like the one in Tehran, has a different significance. We led archaeological digs in northern Sudan, so these projects are rooted in the history of our own collections. In Iran, Egypt, Syria, Tunisia or Algeria, French digs enriched the Louvre and, at the same time, gave birth to their national museums.”

During Martinez’s five-year mandate, the Louvre has more than doubled its digs, opening sites in Italy, Bulgaria, Romania, Egypt, Uzbekistan and Saudi Arabia as well as Sudan. “We also helped train curators and archaeologists from Libya, Tunisia, China and Bosnia,” Martinez says. It is planning exhibitions of its discoveries in Sofia, on the ancient Greek site of Apollonia Pontica, and in Uzbekistan from its digs in the oasis of Bukhara. A show on the Preslav Treasure, Medieval gold jewellery from the first Bulgarian kingdom, opens this month in Paris (until mid-July) before travelling to Sozopol.

In Tehran, the director dismissed accusations from the ultra-conservative press that the Louvre had looted Iran’s archaeological heritage. French digs in Iran started in the late 19th century under official agreements that later shared the discoveries between the countries, he said. Martinez believes that the heritage housed in the Louvre “belongs to everybody—we are only the caretakers”, and that the museum must respond with “improved access and greater collaboration”. It is launching several joint research projects with international scholars on artefacts that were separated at the time of discovery.

Circulating knowledge

For instance, a partnership with the Pergamonmuseum in Berlin will study divinities from the Tell Halaf site, in northern Syria, which “will lead to an exhibition on Aramaean culture next year at the Louvre”, Martinez says. It is also working with the State Hermitage Museum in St Petersburg on a show, opening in Paris in October 2019, of the great Campana collection of antiquities, which the Pope sold to the Russian museum and Napoleon III in 1861. And it participates frequently in year-of-culture exchanges such as 2020’s France-Qatar: a show of Louvre objects is due in Doha.

Has Abu Dhabi ever expressed any annoyance about such projects? The emirate agreed to pay $400m for the Louvre brand as part of its $1bn, 30-year deal with France to establish Louvre Abu Dhabi. Then there is the matter of the ongoing Gulf-Qatar blockade. “Never,” Martinez replies, insisting that the Louvre in the emirate is an “exclusivity” that could not be repeated elsewhere.

Asked whether his predecessor took a major risk by embarking in 2010 on a collaboration with Bashar al-Assad’s government that was halted by the Syrian civil war, Martinez says: “Actually, [Loyrette] was right; given the importance of French archaeology there, we had to go to Syria… and, sooner or later, we shall return.” The Louvre “is not a hostage of political interests”, he says, “but rather a means to help the circulation of knowledge and mutual understanding”.