When Khalik Allah began shooting his sprawling, often abstracted, sleepwalk-like portrait of the street people of Harlem, he had a sense of the world teetering “on the cusp of something, that something was coming around the corner, that the world was about to change.”

The US artist of Jamaican-Iranian heritage, a self-taught filmmaker and photographer, made IWOW: I Walk On Water with this mentality: “That it might be the last movie I ever make, the last time I lay anything on film, so it had to be all and everything.”

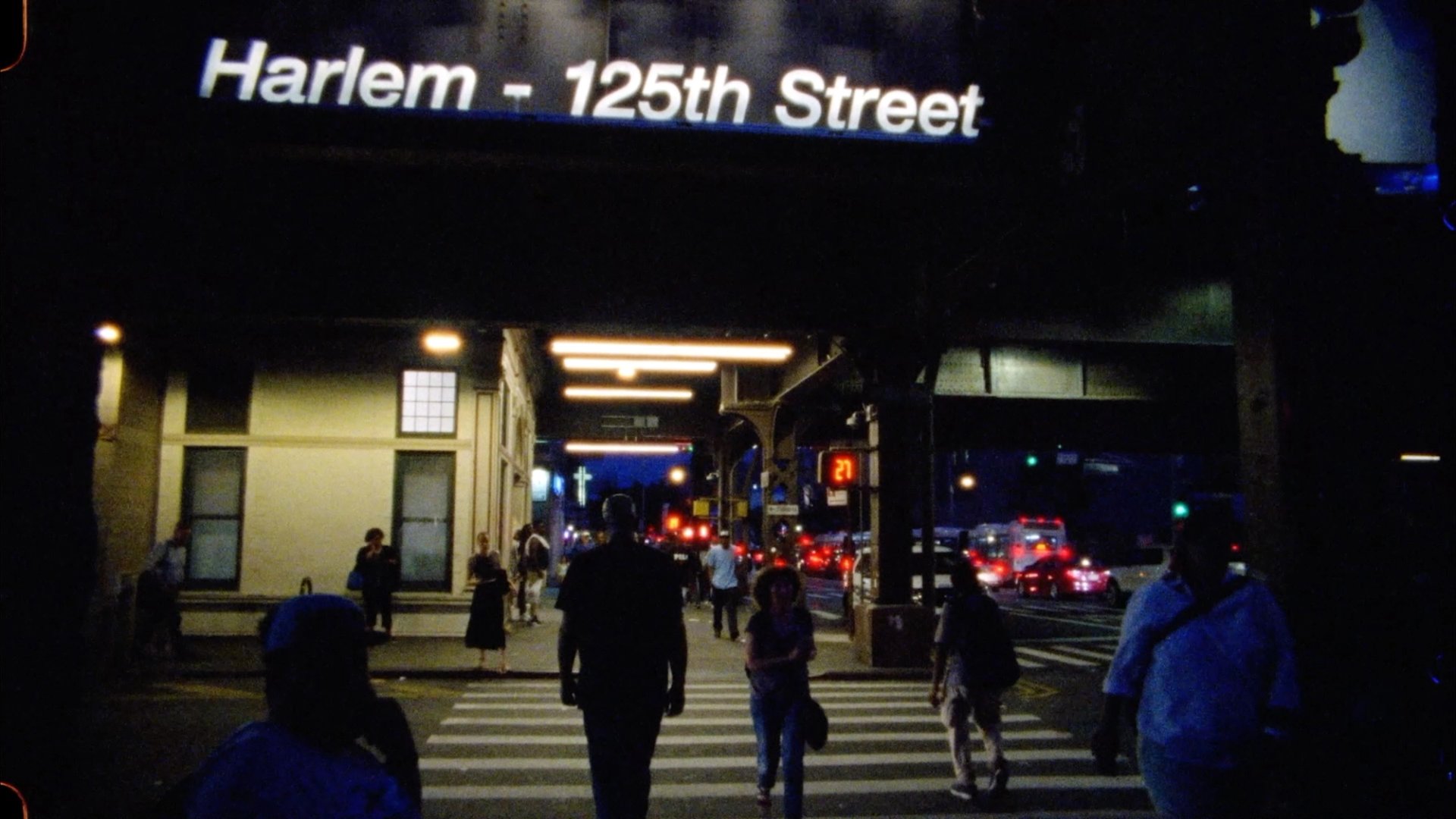

The three hour and 19 minute-long "documentary-poem”—now released in virtual cinemas and on demand by Dogwoof—is shot at night on the corner of 125th Street and Lexington Avenue in Allah’s native Harlem, New York; the corner Lou Reed sang of in Waiting for My Man.

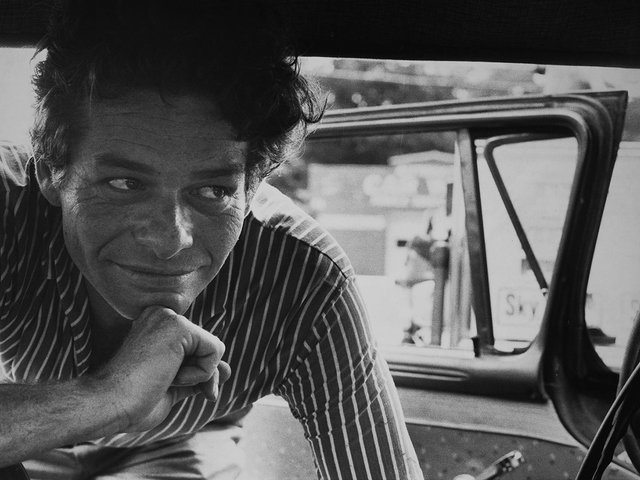

A still from Khalik Allah’s film I Walk on Water Courtesy of the artist and Dogwoof

This same corner served as the setting for Allah’s first feature-length documentary, the acclaimed Field Niggas (2015), as well as his photography book, Souls Against the Concrete, published by University of Texas Press in 2017, a body of work which prompted Magnum Photos to include Allah in their 2020 raft of nominees; “a tremendous blessing,” Allah says today.

Over his five-year artistic engagement, Allah says life on the corner of 125th and Lex hasn’t changed much. “There’s still a heavy police presence, people are still being victimised and oppressed,” he says. “K2 [synthetic marijuana] is still being sold from the corner stores. There’s a lot of pain.”

Shot on 16mm film over the course of eight months, Allah intends the film to convey “a snapshot of life—my life, my relationships, and the life of the streets”. The film conveys Allah’s relationships with the disparate people who somehow exist on the streets of Harlem, and who Allah has developed friendships with over the course of a decade or more—most notably Frenchie, a homeless Haitian man of familial wealth who has lived on Lex and 125th for much of his adult life, and who has acted as a muse and intermediary for Allah throughout.

Aged 36, Allah has led a life of many perspectives; he recounts, as a 20-year-old, walking all night to take portraits before working in a nursing home in Harlem during the day. His work and life is immersed in the teachings and sensibilities of The Five-Percent Nation, a cultural movement influenced by the Islamic faith and founded in Harlem in 1964. When he was nominated by Magnum, Allah told the agency: “The first thing black students are taught is that they were slaves. From second-grade on, your self-esteem is a couple of notches below the white students because you’ve been told you are inferior. That sticks with you and follows you into your adulthood.”

A still from Khalik Allah’s film I Walk on Water Courtesy of the artist and Dogwoof

“The Five-Percent Nation taught me not to take anything on face value,” Allah says. “That teaching has bled into my work. This is a spiritual film. And it’s a holographic film; a piece contains the whole and a whole contains the piece. And it’s an experiential film, one that brings you into an environment that most people would avoid.”

The New York streets Allah shoots are indivisible with the history of street photography. Allah is working in the legacy of New York icons like Diane Arbus, Weegee, Garry Winogrand and Nan Goldin as well as fellow Magnum photographers Bruce Gilden and Bruce Davidson.

But, perhaps unlike some of his current colleagues of the Magnum collective, Allah is deeply concerned with the question of photographic consent. In that sense, Allah perhaps embodies the attitude of a new generation of street photographers; ones who see the camera as a way of being alert and alive to social and racial injustice.

“It’s important to speak to whoever you’re working with,” Allah says. “To share your intentions with your subjects. To properly introduce yourself, and to get permission and consent. As photographers, we’re responsible for the work we make, and we need to be conscious of that. That involves not shooting somebody that doesn’t want to be shot. That’s a basic thing. And don’t shoot children without a parent’s consent. That is very important to me.”

A still from Khalik Allah’s film I Walk on Water Courtesy of the artist and Dogwoof

Allah, then, only shows in his photographs a tiny fragment of the relationships he has established. “The conversations that normally don’t get captured on the emulsion.”

Beyond the streets, the film also contains often fraught conversations Allah has with his parents and loved-ones; on occasions, he continues to shoot whilst under the influence of psychedelic drugs; the film’s title, I Walk on Water, is a reference to a magic mushroom-induced trip Allah filmed during which he believed he was the reincarnation of Jesus Christ. There’s the introverted, intensely personal and confessional conversations Allah has with his girlfriend Camila—a relationship that came to an end after shooting had wrapped, he says.

Why did he feel the need to imbue this portrait of Harlem with such unvarnished insights into his most personal spaces? “It’s not something I would continue with,” he says. “To me, it was maybe the first and the last time I do something like that. But I felt the film warranted that openness and honesty. I was filming people in the streets, the rawness of their street life. I didn’t want to make a distinction between them and my family, or my girlfriend at the time. I wanted to treat them all equally. We’re all God’s children.”

Allah is now shifting his focus to narrative feature films. “I’m going through a stage of reinvention, of renewing myself,” he says. “Expect something a lot different.”

• IWOW: I Walk on Water is released by Dogwoof on 26th February