• This article is from The Art Newspaper's archive. It was published in our December 2007 issue.

Jean Pigozzi

Turin-born Jean Pigozzi is a large, forthright man with the indefinable accent of someone educated internationally. The money originally came from Simca cars, founded by his father and sold to Chrysler in 1962. For a while he worked in the accounting side of the Hollywood film business, but then became an investor in venture capital. He is the backer of the Liquid Jungle Lab in Panama, working on high-tech ecological research, but in the last 18 years has also built up the world’s largest collection of contemporary African art. A hundred or so works are currently on display in the Pinacoteca Giovanni e Marella Agnelli in Turin until 3 February 2008 in a show called “Why Africa? The Pigozzi Collection”. The curator of the exhibition is André Magnin, who has worked with Mr Pigozzi from the start in acquiring the art. Mr Pigozzi says the fact that Mr Magnin is a Frenchman has probably meant that the collection favours artists from the French-speaking parts of Africa. In this interview, he explains the pleasure the formation of this unique collection has given him.

The Art Newspaper: What is the first work of art you remember?

Jean Pigozzi: My parents were typical bourgeois of the 1960s and they had a Renoir, a Sisley, the odd Boudin. I would look at these and be completely uninterested. By the age of 15 I understood there was something else; I saw a bird by Klee for sale and I told my mother, you should bid on it. Then I went to college in the US and started to visit MoMA nearly every weekend and that opened my eyes. I became friends with Warhol and my professor at at Harvard was Doug Hubler, who was a minimalist artist. I started buying in 1971: a little drawing by Sol LeWitt for $500-$600. I put together a collection like that of a dentist from Cincinnati—a Warhol, a Schnabel, a little Clemente—but I knew it was not interesting. I became friends with Charles Saatchi about 1980 and then I understood what serious collecting was. So I decided to make a collection of art that cost less than $5,000 and went round the galleries in New York, but it was very difficult because there was a peak at that moment and you had to be on a waiting list.

I feel that at the time of the Medici they had my kind of rapport with their artists

Then, by pure chance, I went to the exhibition Les Grands Magiciens de la Terre in Paris on its closing day in 1989 and it was a revelation. I discovered all the African art—I had no idea they were doing painting and sculpture—so the day after I called the Beaubourg and said, can I buy it all, and they said, no, the sponsor, Canal Plus, gets to keep it all, but you can meet the curator, André Magnin. He had no job, so I said, work with me, and we have been together now for 18 years.

Romuald Hazoumé, Cargo (2006) Courtesy-C.A.A.C. - The Pigozzi Collection, Geneva, Photo : Romuald Hazoumé

Do you go round Africa yourself?

I have never been to Africa. I want to keep my illusion about it being a nice, friendly place. If you look at the New York Times, all you read about is corruption, Aids, Darfur, wars. But my collection is not really political. I try to see another side of Africa, where, out of all this mess, artists in ateliers the size of shoe boxes, with children and noise, manage to make incredible art, as good as what is being made in SoHo with three assistants in white gloves and all that. What I am interested in is the power of the artist that comes from inside.

How does your curator André Magnin find out what there is?

André has been going to Africa for 22 years so he has a network, friends of friends. Sometimes the artists find us. We buy very little from galleries—in South Africa there are a few—but directly from the artist. We give them money in advance and say, we will be back next year. Sometimes they disappear, sometimes they haven’t done anything, sometimes they have spent all the money and have none left to buy paint and canvas. You never know; it’s not like going to SoHo with three little girls in black dresses who run around holding the paintings. What we do is completely different, It’s hours of driving in a Land Rover to where someone unrolls something in the back of a little shack. It’s labour intensive and complicated and that’s one of the reasons why nobody else has bothered to collect African art.

What has happened to the artists you have bought now that half a generation has gone by?

Some of them have become quite famous, such as Malick Sidibé, who now has a comfortable life and won the Golden Lion at this year’s Venice Biennale. Romuald Hazoumé also has a gallery, but for some of them nothing much has changed. Some of them are complicated people who don’t really understand how to do it and don’t really want to do it. It’s very uneven. Chinese art is a huge speculation, and in India there are rich people buying art, but in Africa a rich person buys a Rolex with diamonds or a new house or bullet-proof Mercedes; buying a painting is very low down the list. The only people who buy art there are embassy people, doctors, a few tourists.

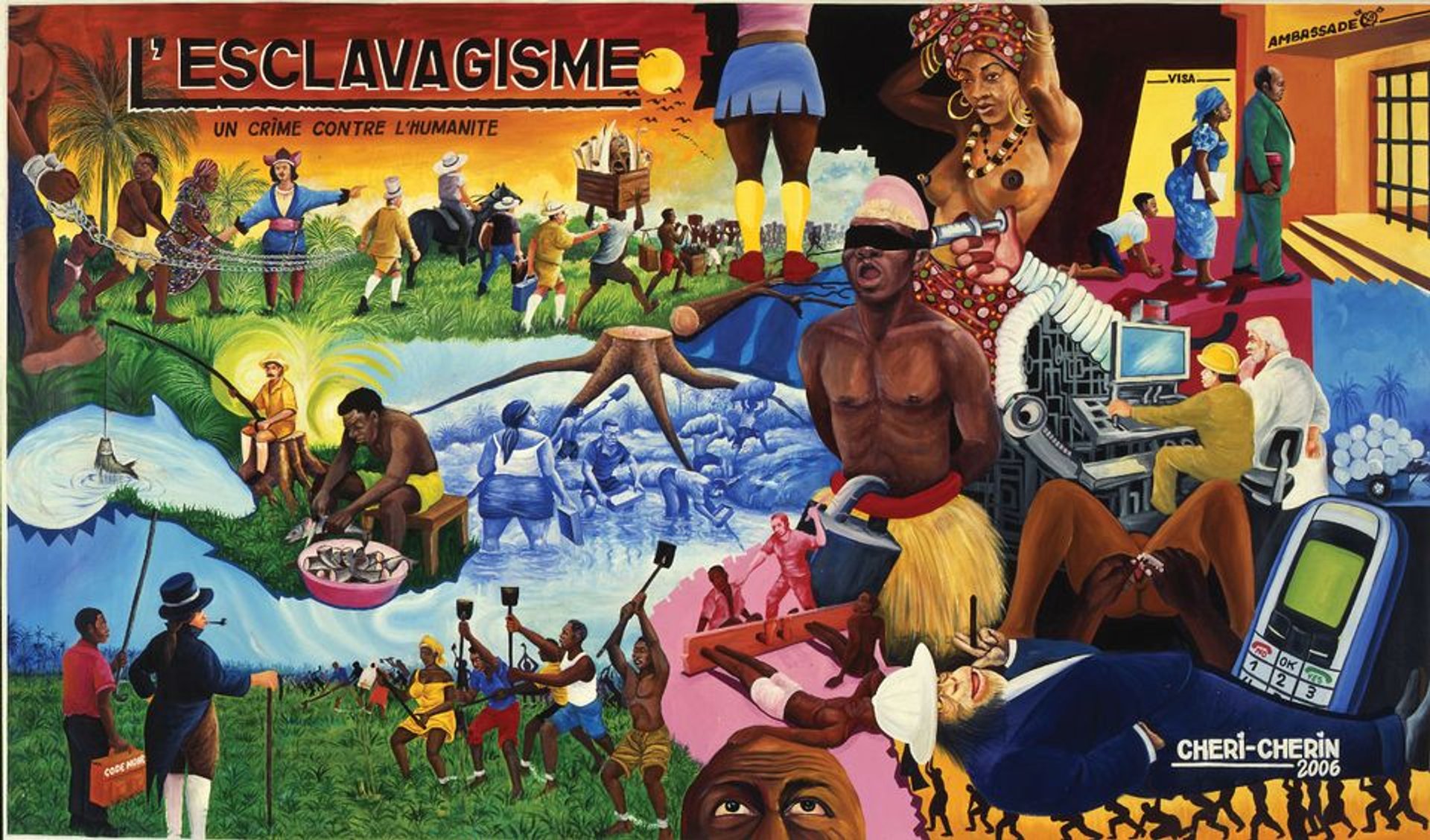

L'esclavagisme, Chéri Chérin (2006) Courtesy-C.A.A.C. - The Pigozzi Collection, Ginevra Photo: Maurice Aeschimann

Why does an African become an artist if fine art is not part of their culture?

To be an artist in Africa is a bizarre thing. That’s what I like about them: the people in my collection have to be really, really determined. Sometimes I am the only person who buys art from them. They are not businessmen either. A lot of these young artists in the West are thinking, is it better for me to have an article in Women’s Wear Daily or should I go out with that girl, or should I dye my hair pink? These Africans really are artists in the way you can imagine Picasso being in the 1920s.

I try to see another side of Africa, where, out of all this mess, artists in ateliers the size of shoe boxes, with children and noise, manage to make incredible art, as good as what is being made in SoHo with three assistants in white gloves and all that.

Is it partly the purity of this art scene that appeals to you?

One thing I like is that we deal directly with the artist. Let’s say I wanted to buy a Kiefer, the likelihood that I would meet the artist is very slim. I would meet his gallery owner, the curator, but never the great creator himself, except perhaps at an opening to shake his hand. I spend a lot of time with my artists. There is no buffer between me and them. I am not interested in gallery owners, curators and critics. If an African says, indicating the size, “This picture costs $2,000, but if you want it bigger, it’s $4,000,” that’s fine with me; I like the simplicity of the rapport. And I can say to him, “You know, what you did last year was more interesting,” and he says, “Why?” and I tell him why and he says, “I’ll think about it”. But I’m not going to say that to Francesco Clemente. I feel that at the time of the Medici they had my kind of rapport with their artists.

When did you start showing your collection?

About 15 years ago. Since then I’ve had shows in Houston, Bilbao, the Smithsonian, Monaco and now Turin. We had a big show of Chéri Samba at the Fondation Cartier in Paris and at the Ikon Gallery in Birmingham. I’ve currently got seven paintings at Tate Modern (“ ‘Popular Paintings’ from Kinshasa”, until 1 March, 2008). One day I want to build a museum. I want it to be the ambassador for Africa, so the place would be New York, the centre of the art world, or perhaps Paris.

How many pieces do you have?

Over 10,000, which I keep in a warehouse in Switzerland.

Do you feel the world is beginning to catch up with you? There was the Africa section in this year’s Venice Biennale.

Look at MoMA, at Tate, at Beaubourg: there’s not one museum that has a contemporary African section or curator. And as for collectors, I know people who have a few pieces, but they don’t really focus on it the way I do. The African art scene is not organised, there’s no money in it, so people don’t get involved.