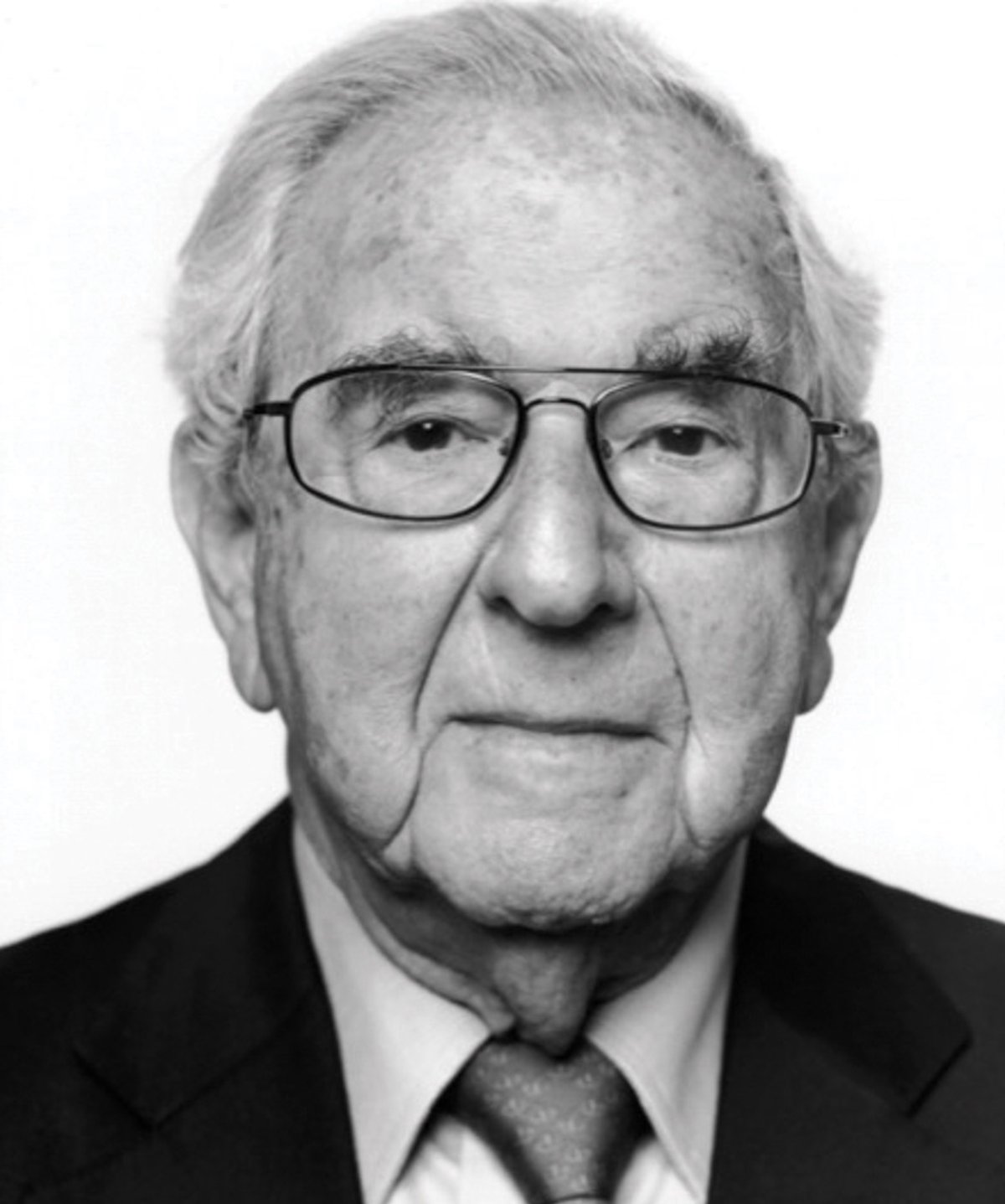

“I can’t slow down, I’m afraid. I’m not sure if I’m working because I’m in good health, or if I’m in good health because I’m working.” So says the 102-year-old art appraiser Alex Rosenberg. In June, he took a biannual seven-hour exam to renew his appraiser’s qualification, “to make sure that I’m still of sound enough mind to do it. But if I live another two years, I promise I won’t take the test again”.

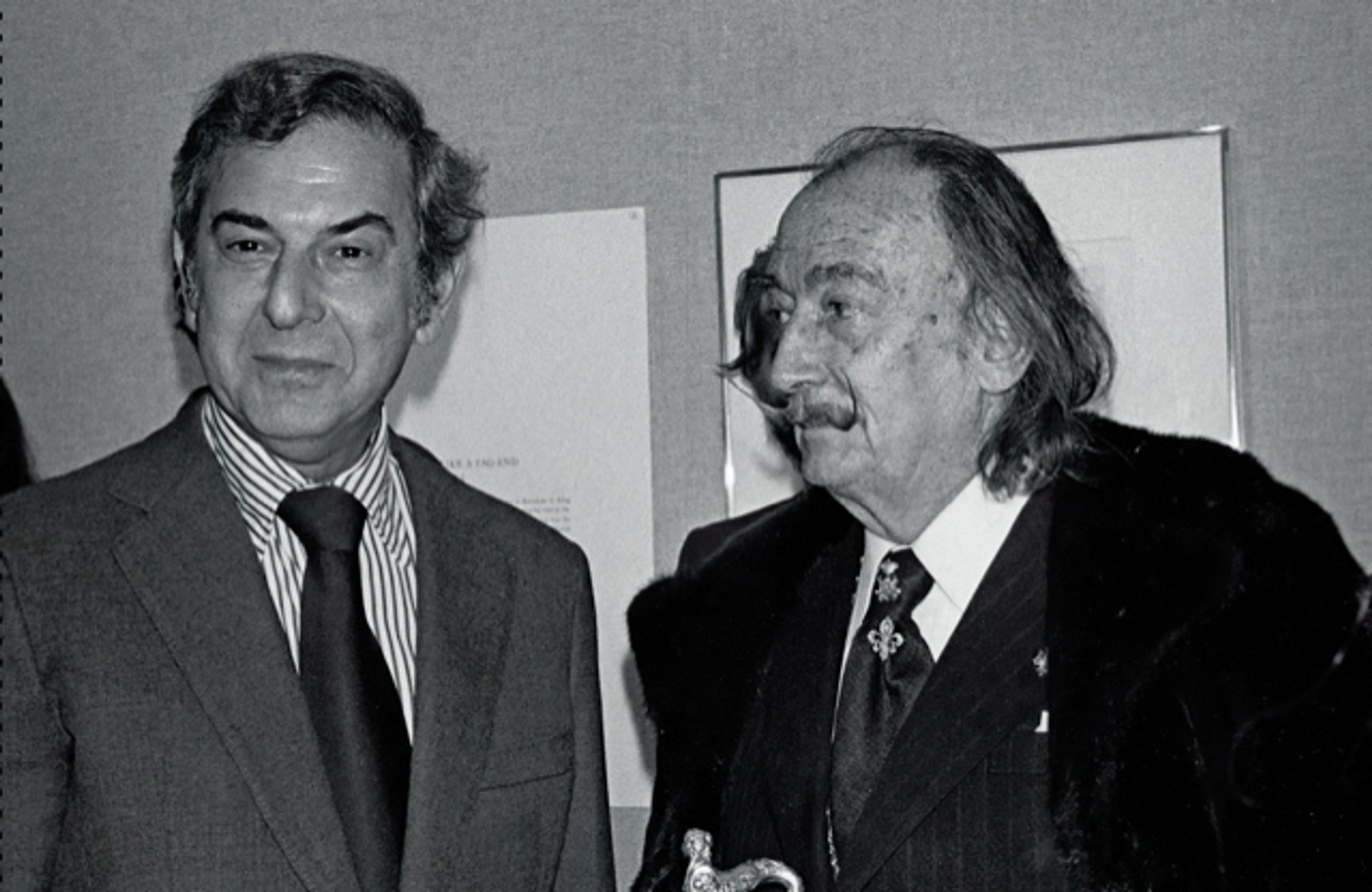

Born and raised in Brooklyn, in previous lives Rosenberg served as a pilot in the US Air Force during the Second World War, was a political activist (he was a delegate at the 1968 Democratic National Convention), a publisher of prints for artists such as Salvador Dalí, Alexander Calder and Henry Moore, and an art dealer. “I always knew I would end up in something as disreputable as the arts,” he says.

It was after Rosenberg closed his gallery and retired (in the loosest sense of the word) that he became an art appraiser, in 1985—he is now a life-certified member of the Appraisers Association of America (AAA). “When the entire art market was changing from a cultural body into an economic body, I was unprepared,” he says. “My old training had been to see art as culture, not as a financial asset, and I had to figure out something else I could do.” And it is a fairly lucrative retirement diversion: Rosenberg charges $500 an hour.

“At my age, if something isn’t challenging it’s hard to make it work,” Rosenberg says on the phone from his Long Island home. “I need a stimulus to keep going. When you’re younger, the stimulus is there all the time but at my age, it takes something extra to keep you going.”

That extra challenge is his expert witness work, including in the Knoedler gallery fakes case and the valuation of Robert Rauschenberg’s estate in 2014‚ which he put at $1.7bn. He is currently valuing the estate of a “major art dealer who died early this year”.

Appraising, Rosenberg says, “is neither an art nor a science—it’s a combination of both and the ability to extrapolate, to take various bits of evidence and come up with a logical conclusion.” And he is vociferous on one thing: authentication is an entirely different skill: “Appraising is done on the assumption that the work is authentic. If you have doubts that a work is authentic, you should not do an appraisal. You have to know the person for whom you’re working and their reasons for doing the appraisal. If you don’t, you may be working for criminals.”

In the Rauschenberg case, in which three trustees of the Robert Rauschenberg Revocable Trust were suing the artist’s foundation for $60m in fees, Rosenberg argued an earlier valuation of the artist’s estate by Christie’s was now outdated and too low: “It was my job to prove that A: [Christie’s findings] were out of date and B: what the new values were…we had to establish the fact that it wasn’t a criticism of Christie’s, it was a change of circumstances.”

Rosenberg with Salvador Dali Courtesy of Alex Rosenberg

How did he deduce the value? “I took sales that had taken place at Gagosian and several Texas galleries, the insured value that the estate and certain museums had on his art, and from that I came up with a factor. That factor was applied to Christie’s values, bringing it up to that amount [$1.7bn].”

The De Sole vs Knoedler case was quite different, Rosenberg says: “The government’s position, which is still under investigation, is that one Chinese painter (Pei-Shen Qian) created all these fake works [sold by the gallery]. However, I disagree because the fakes included around ten artists and I don’t believe that any one person can copy ten different artists and each one be so good that it escapes the attention of the primary experts in the US.” It became Rosenberg’s task to prove that the gallery was not committing fraud because it had performed due diligence: “Ann Freedman [the gallery’s president] was a risk because we had to prove that she was a dealer not an expert. Dealers are not experts, they’re sales people.”

In Rosenberg’s view: “The customers were defrauded, but not because Knoedler was aware of it.” Asked if he thinks Freedman was complicit in selling fakes, Rosenberg says: “My job was to prove that she had done what you expect a dealer to do before selling a work of art…It’s impossible for me or anyone else to read what’s in her mind.”

Different times

The art market has changed beyond all recognition since Rosenberg started out in the 1940s, when “art didn’t have any commercial value, at least not the art the middle classes could afford”. Rosenberg takes a dim view of today’s contemporary art market: “What happens is a very wealthy person is working together with one of the top galleries and suddenly you see a lot of publicity for an artist. Then you see their work at auction and there’s a big hoopla, the prices are up high. The next year, you hear nothing because they didn’t sell enough and they couldn’t continue the sponsorship. But it’s all unofficial.”

All of that contributes to Rosenberg’s theory that the art world today has one major purpose—to create loans for banks or other investment groups: “The profit now is in lending money for people to buy things. Art is now an investment vehicle.”

Unsurprisingly therefore, Rosenberg won’t value contemporary art: “One artist continues to do well, the other nine do not. The current selling price is not the appraised value…I don’t touch contemporary art because not only does it baffle me, but you can’t come up with any hard evidence. It’s a gamble.”