Born in Liverpool to Punjabi parents, Chila Kumari Singh Burman has explored her British-Indian heritage and what she describes as “the experiences and aesthetics of Asian femininity” for more than 40 years. Her exuberant work spans painting, printmaking, collage, photography and performance: Bollywood bling meets Pop art, with lashings of colour, glitter and a defiant refusal to be constrained within a single approach or interpretation. Burman was a member of the British Black Arts movement in the 1980s and one of the first South Asian women to make political art in the UK. Her work remains infused with messages of female empowerment and a desire to explore multiple cultural contexts and identities, as is demonstrated by her current work on the façade of Tate Britain. This envelops the building in kaleidoscopic references, from Indian mythology to George Orwell, via the 19th-century “Warrior Queen” freedom fighter Jhansi Ki Rani and the cornets sold out of Burman’s father’s ice-cream van.

The Art Newspaper: What is the thinking behind your Tate Britain Commission?

Chila Kumari Singh Burman: I want people to go: “Wow, is that really Tate Britain?” It’s got all the elements of what I work with, whether it’s photomontage, collage, painting, bits of my etchings or iPad drawings. I want to talk about my position as a South Asian woman growing up as a Punjabi Liverpudlian, and to give my take on traditional and popular Indian culture. My idea is to disrupt the Neoclassical façade and mash it all up—it’s my take on the world as it is, defacing and refacing and putting chaos into order. There’s all kinds of things from my past: neons of the Bengal tiger that was on my father’s ice-cream van, a peacock like those in Hindu temples and me doing a Shotokan martial arts jump. Up with Britannia on the top of the Tate pediment I’ve put a figure of a Bollywood actress with a raised fist that we put on the cover of Mukti, a magazine for South Asian women that I was involved in founding in the 1980s. She’s my version of Kali, the goddess of creation and destruction, and I’ve added the words “I’m a Mess” that I found on a badge—because right now in Britain we are in a mess, aren’t we?

Running along the façade frieze is the phrase, “Remembering a Brave New World”. Why did you choose this title?

It suggests that inspiration can be found in the past, and it also offers a sense of hope for the future and faith for a brave new world. It has a double meaning as Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World was a dystopian, totalitarian state under constant surveillance. I know some people might ask, why are you quoting this white, male upper-class character who went to Eton? But Huxley was so much ahead of his time; he was a brainy fellow.

Chila Kumari Singh Burman's commission coincides with the Hindu festival of Divali, which she says "is about the light at the end of the tunnel, about good over evil" Photo: © Tate 2020/Joe Humphrys

The commission also coincides with Diwali, the Hindu festival of lights.

The date of Diwali changes every year and it happened to be when Tate wanted me to do the commission. So it offered me a great opportunity to put Diwali on the Western art world’s landscape. The festival is about the light at the end of the tunnel, about good over evil. So I’ve added Lakshmi, the main goddess of Diwali, of wealth, fortune and luxury, and I’ve put in the god Ganesha, too, who is also worshipped then and brings fortune and luck. When I was growing up, we didn’t have art on the walls but there would be these calendars with gods and gurus everywhere; I’ve made Tate Britain a bit like a contemporary temple, but not so much to do with anything religious.

You’ve described your work as “all blinged-up with a razor-sharp political awareness”.

There’s an abundance of decoration and embellishment. I use adornment, but with a message. Every single element I’ve included at Tate Britain has a reason behind it. On two of the pillars are images from my Punjabi Rockers prints—the title and content combines me being a Punjabi with my love of all kinds of music, whether hippie, punk, reggae, or the Bhangra and Bollywood film music my parents played at home. Then the central pillars have Indian firework packaging with Lakshmi and Ganesha that references Diwali. The other pillars have flowers and details from my Jelly Handcuffs series of works. On the steps are my kaleidoscopic iPad drawings, which refer to Indian fireworks, and right at the centre over the main door is the Hindu ‘aum’ symbol. I was brought up going to the Hindu temple every Sunday, and I’m sure that’s where I get my sense of colour—you’ve got all the gods and it’s totally kitsch and over the top. I used to love getting dressed up to go to the temple; since the 1980s I’ve been exploring the experiences and aesthetics of Asian femininity, which has often involved me playing with the formal properties of “girly” accessories—bindis, bras, flowers, jewellery and makeup—to explore gender and race. I like to take the idea of Arte Povera and recycled materials one feminist step further by using cheap, pretty detritus that wouldn’t usually be considered worthy of contemplation.

You went to art school to escape an arranged marriage and then went on to be closely involved in the British Black Arts movement. What was it like to be an artist at that time?

I was never allowed to go out and I didn’t have a boyfriend until I went to Leeds Polytechnic in 1979. It was a fantastic time to be an artist because it was the time of punk and Rock Against Racism, and there was a growing interest in performance and Marxist, feminist art. I played in a woman’s punk band called Delta 5—it was very much sex and drugs and rock’n’roll. In the 1980s I was at the Slade and it was a highly experimental, politically charged time. Politics, art and music felt more connected with ideas around race, class and gender. Then, after leaving the Slade I got involved with a group of South Asian women who set up Mukti, an Asian feminist magazine published in six languages. I joined a number of activist groups as well as curating Curation for Liberation at Brixton Art Gallery and Artists Against Apartheid at the Royal Festival Hall with Darcus Howe. I also designed the anti-racist Southall Black Resistance mural with Keith Piper. We all just thought we had to do our own thing because the white art world wouldn’t take any notice of us. I’ve always been an activist and an artist—there’s never been a shortage of things to comment on.

In 1988 you wrote your now seminal essay, There have always been Great Black Women Artists, in response to Linda Nochlin’s Why have there been no Great Women Artists? How do you feel things have progressed?

There have been huge changes—the existence of our art is now more acknowledged—but there is still much more to do. A great many artists outside the dominant culture—and especially diaspora artists in Britain—are still missing from major art collections, and there are not enough monographs, retrospectives or selection for commissions and international exhibitions. That’s why me at Tate Britain is so fabulous.

Three key works

Courtesy of the artist

Cornets and Screwballs Go Vegas (2010)

Bachan Singh, my Dad, came to England in the early 1950s and first of all he worked for Dunlop in Liverpool, but then he got an ice-cream van. He was also a magician who would eat fire, razor blades and crushed lightbulbs and was a regular act at the Seaman’s Club as well as being a skilled bespoke tailor. He sold ice cream on Freshfield Beach for over 30 years and had this big van with a Bengal tiger on the top. All through the 1970s I used to help in the van and clean it every evening after school—there was no time for homework—but I got to eat as many flakes and ice-cream cornets as I liked and was immersed in a world of colour, flavour and materials. So this piece is all to do with the ice-cream and the whole Mr Whippy thing—I couldn’t even make one, my brothers and Dad did—it’s dead hard. The Screwballs are plastic and I sprayed the cornets with spray mount and covered them not with hundreds and thousands as I did with the van but instead I gave them more of a Punjabi feel by dipping them in glitter.

Courtesy of Tate

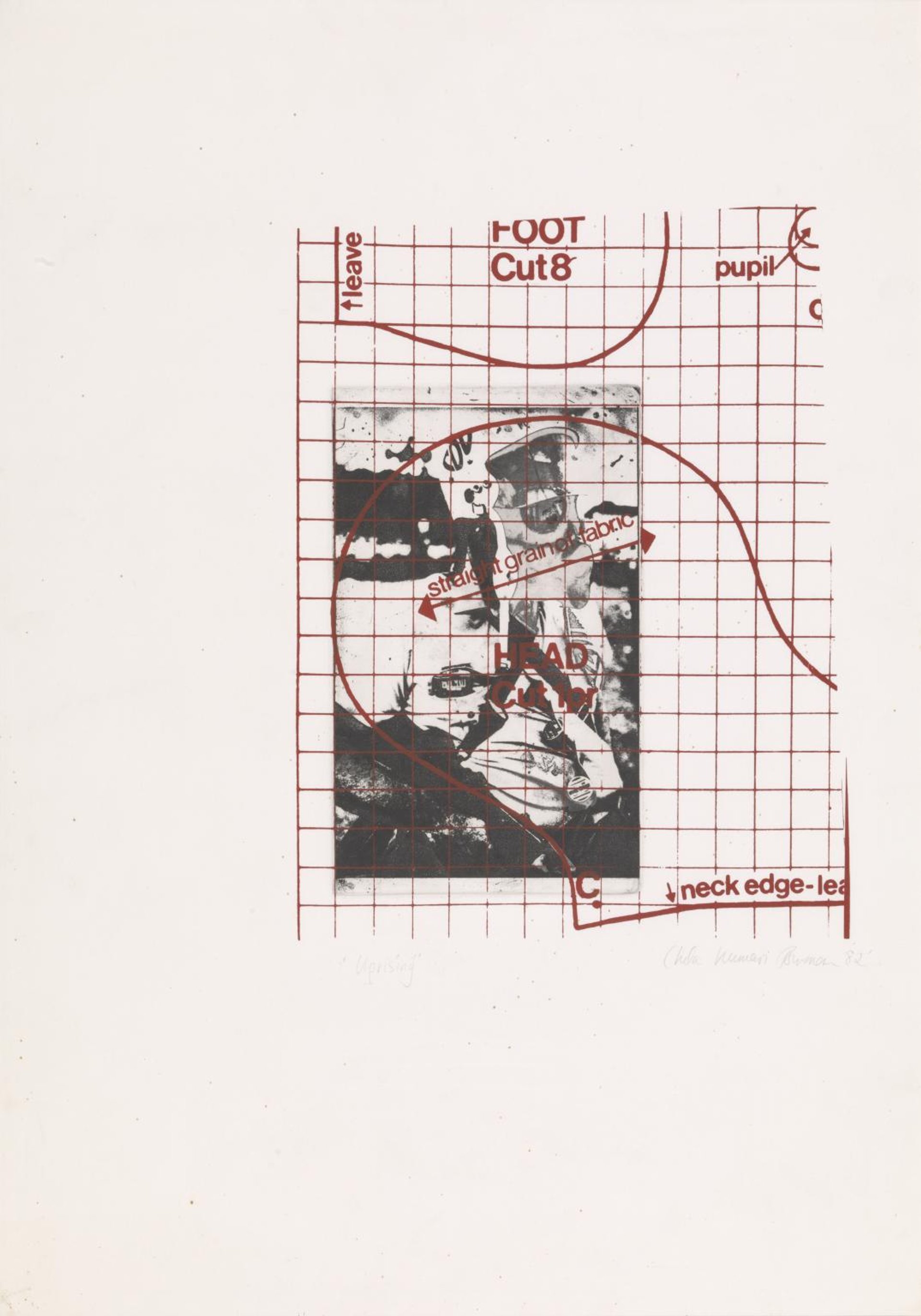

Cut–Foot–Pupil–Uprisings 1981

These two black and white images of a policeman overlaid with a red grid-based sewing pattern for cutting out a garment are one of six unique prints which were a response to the 1980s riots. I was doing my MA at the Slade and living in Brixton at that time and my partner got thrown in jail by the police for running down a side street during the riots in Leeds. The prints were made with the master printmaker Stanley Jones in the Slade’s printmaking department which had a reputation for experimenting with a range of techniques, and here I’m combining etchings with silkscreen and lithography. I like mashing things up and I don’t follow the rules, even when it comes to printmaking. In this one you’ve got a plate with all the gas masks on but I put it in the acid bath so bits would drop off and there’s holes in them. I didn’t like the police at that time so I did an American cop and put him in an acid bath too, and over it I put this paper pattern with cut-outs on it. The tensions and disjunctions in the layering and the fragmented images reflect the violence and the conflict of the subject.

Courtesy of the artist

Dada and the Punjabi Princess (2017)

This is a multi-layered psychedelic animated film with a name that combines my love of the Dada movement and the fact that my middle name Kumari means princess in Punjabi. My dissertation at Leeds was on Dada and Surrealism as political and revolutionary movements as opposed to aesthetic movements and the piece also comes out of my Bindi Girls, a series of female figures composed almost entirely of colourful and glittery bindis, gems and crystals. Someone said to me, why don’t you make these move and revolve as an animation? So I found these two Indian dancers, one from North and one from South India, put a green screen up in my studio and got some of the most talented students from the University of the Arts MA in digital art to help me make the film. It’s a mash-up of punk, pop and Bollywood for the digital age—the Indian dancers move across the screen in a series of movements that resemble traditional dance as well as martial arts movements and it’s all underscored by a Punjabi folk song with a drum’n’bass breakbeat mixed by my brother, Ashok. The film is about a girl who goes through the world with all the emotions, like Lara Croft. She has all the emotions that us girls have to deal with—joy, sadness, depression—and then she comes out on top.

Biography

Born: 1957, Liverpool

Lives: London

Education: 1975, Southport College of Art and Design; 1976-79 BA in printmaking, Leeds Polytechnic (now Leeds Metropolitan University); 1980-82 MA in fine art, Slade School of Art, London

Key Shows: 2017 Science Museum, London; Wolverhampton Art Gallery; Nottingham Contemporary (touring); 2015 Rich Mix, London; 2013 SOAS, London; 2011 Paradox Gallery, Singapore; 2006 University of Greenwich, London; 2004 Plymouth Arts Centre (touring); 1999 Andrew Mummery Gallery, London; Victoria and Albert Museum, London; 1995 Camerawork, London (touring); 1990 Horizon Gallery, London; 1988 One Spirit Gallery, London.

• Tate Britain Winter Commission: Chila Kumari Singh Burman, until 31 January 2020. Another interview between Louisa Buck and Burman can be found on this episode of our podcast The Week in Art