An artist walks through a snowbound landscape in upstate New York, on his way to toil in his woodshed studio. He spoons paint onto his palette with his hands before applying bright colours to a vast canvas. This is Larry Poons, the unlikely star of The Price of Everything, a new documentary film by Nathaniel Kahn exploring the grittiness of the contemporary art market. We see Poons preparing for a show of new paintings organised by the dealer Dennis Yares last year, but he is presented as the antithesis of art market superstars. On camera, Poons decries the market for preferring his “old stuff” and rails against the notion that the “best artist is the most expensive artist”.

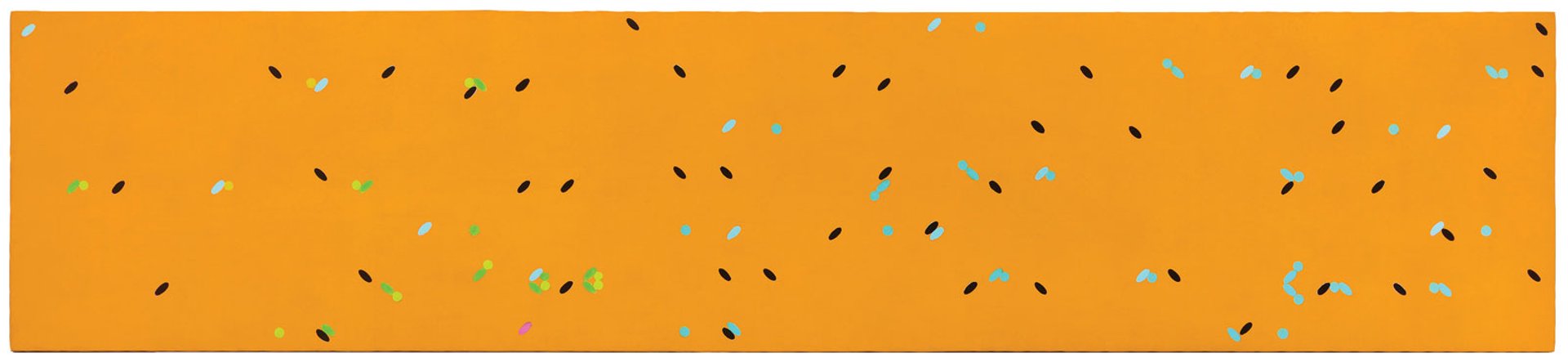

Poons has reason to be suspicious. After studying at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston from 1959, he moved to New York, where he gained immediate acclaim for his grid-based “dot paintings”. In 1963, he had his first solo exhibition at the Green Gallery and he was the youngest artist in The Responsive Eye, a survey of post-war American art at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, in 1965. But his art became more radical and although he continued to show his work in New York and it was still admired by critics, it proved less palatable for the market.

Museums just want to play the latest hit songs

In the film, the artist’s perennially lyrical ideas around the purity of art, his physical connection with paint and his work’s modest rise at auction in recent years provide a stark juxtaposition to scenes of market darlings like Jeff Koons, shown in his expansive New York studio while throngs of young assistants work round the clock to complete pieces that fetch millions despite being virtually untouched by the artist.

The documentary, which premiered at the Sundance Film Festival earlier this year and began touring select North American cities in October, also features cameos by auctioneers, collectors, dealers and critics, along with other artists including Gerhard Richter and Njideka Akunyili Crosby.

Poons’s acclaimed dot paintings include Imperfect Memento: To Ellen H. Johnson, 1965 (1965) Courtesy of the artist

The Art Newspaper: You mention in the film that, when you stopped painting dots, your old friends stopped talking to you. What inspired your shift in style?

Larry Poons: It depends on what you mean by inspiration. Painting in itself is self-generating. Everything affects us as long as we’re alive and inspiration is a very catch-all, comic-book word. You’re not the same person that you were when you were eight years old and learning arithmetic. It’s impossible to stay the same unless you’re catatonic. Much like Leonardo da Vinci said, a work of art is never finished, only abandoned.

What’s your process like?

I never quite understand what people mean by “process”. What’s your process like? You just sit down at your typewriter and start writing and one word follows another. What was Rembrandt’s process like? He simply started. If you were describing a tooth extraction, there would be a series of steps required to take out the tooth, but there’s no definite steps in painting. There’s no process in painting that you can do that’s wrong or right, so it’s outside of the dimension of what we associate the word “process” with. There is no process except getting out of bed in the morning and feeling like painting and going to paint. The process is just painting.

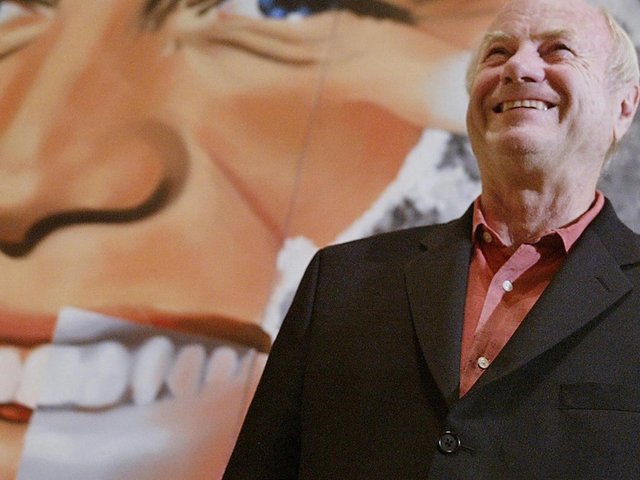

Larry Poons was part of a group exhibition at New York’s Museum of Modern Art in 1965, before his work became more radical Photo: Jason Mandela, Courtesy: Loretta Howard Gallery

How has the New York art world changed?

I don’t think it’s ever changed: it’s just much larger now but I don’t mean “larger” in the sense of “important”. I’ve been showing paintings steadily every year in New York since 1963 but people weren’t always reading about me because my work wasn’t Pop art: it wasn’t the “in” thing for quite a while. I haven’t been isolated from the art world, it’s the art world that’s been isolated from me. Museums just want to play the latest hit songs, and they stopped playing my songs for a while.

What has been your experience dealing with the market?

I’m not a gallery owner or someone who buys paintings. I’m a painter, so I don’t deal with the market. Before there was an art market, there were people painting in their caves. People just looked at the pictures and didn’t worry about what they meant or how much it cost.

How would you define success as an artist?

Success is in the studio. That’s the only success there is. The only other type of success is business: it’s not art. There’s nothing wrong with business and there’s nothing wrong with art but they’re two separate things. If you define success as being able to sell something to pay the rent, then that means you’re successful at paying your rent. It doesn’t mean that your art is any good or not.

Do you have any advice for young artists?

Make it as good as you can. The advice I sometimes give is to paint what you can paint. If you can’t paint figures but you can paint rocks, then paint rocks. If you keep working at it, you’re going to get better and better. As you go on, things that you could never do come about naturally. You’ll find that things just happen. I think Allen Ginsberg once told a fellow writer, maybe Jack Kerouac, “First thought, best thought”, which is pretty much what I’m saying. First colour, best colour. Next colour, next colour. Then, all of a sudden, you generate something new.

• The Price of Everything is shown on HBO on 12 November and in UK cinemas from 16 November