“Dismantling, re-imagining and re-purposing this outdated racist infrastructure is an urgent task”Dan Hicks

A new book called The Brutish Museums about colonial violence and the restitution of stolen objects could not be more timely after France's National Assembly voted to return 27 colonial-era artefacts from French museums to Benin and Senegal. The book by Dan Hicks, a curator at the Pitt Rivers Museum and professor of contemporary archaeology at the University of Oxford, focuses on the pillaging of the Benin Bronzes in the late 19th century and fuels the debate around cultural restitution, repatriation and the decolonisation of institutions. Following a British naval attack in 1897, thousands of Benin Bronzes—brass plaques and sculptures depicting the royal court of Benin City in modern day Nigeria—were pillaged and subsequently ended up at some of the most prestigious museums in the world.

A brass plaque from Benin City looted by George LeClerc Egerton, an admiral in the British Royal Navy

The Art Newspaper: Had the idea for the book been fermenting for a while? You have said in the past that the seed was planted two decades ago after conversations with the Belgian archaeologist David Van Reybrouck.

Dan Hicks: Yes, the idea for The Brutish Museums was in incubation for almost two decades. I knew I wanted to interrogate the stories we tell ourselves, and those we don’t tell ourselves, about Britain’s role in the so-called Scramble for Africa [at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th century]. Through friends and colleagues in Belgium, Germany and France I learned about the growing public consciousness of the scale and horror of corporate, militarist colonialism in Africa after the Berlin Conference of 1884.

A new reckoning with this very modern layer of the imperial past was developing in Europe, and ten years ago David Van Reybrouck’s book Congo was an important catalyst. I wanted to interrogate the relative silence about Britain’s role in the dispossession of the continent of Africa. From this initial question, the book took shape after 2007, when my appointment as curator at Oxford’s Pitt Rivers Museum forced me to consider how the Benin Bronzes, and the 1897 Benin punitive expedition, fitted into that story. Such curatorial “excavation” takes time, but 13 years on the book shows the results of that digging.

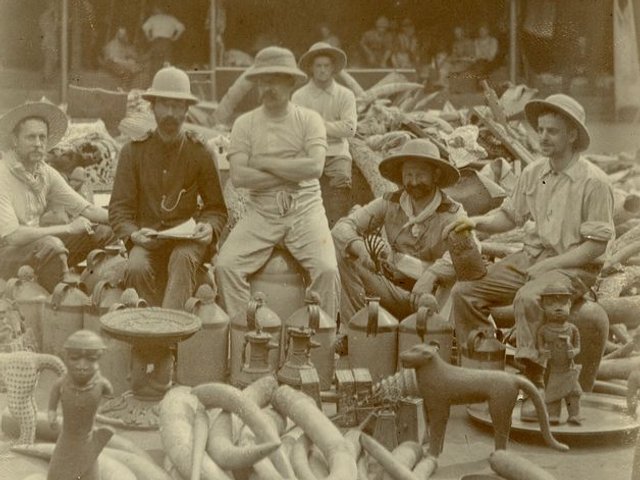

The Royal Palace in Benin City during British looting in 1897

What, for you, is the most startling aspect of the pillaging and subsequent acquisition by museums of the Benin Bronzes? Is it the fact that “museums know so little about what they hold, and they share just a fraction of what they could know”?

It’s certainly astonishing, and shameful, that so many museums understand so little about their African collections and their provenance. But actually, my most startling discovery was this: I never imagined art might ever have played anything more than a quite peripheral role in global history. In the case of the Benin Bronzes, I’d always believed what I’d been told: that there was some grim, transactional justification for the looting—to defray the costs of an expedition as a justified reprisal. But as I researched this book, that story fell apart. In reality the looting was a chaotic free-for-all. Fewer than 100 looted bronze plaques were officially sold by the crown agents for the colonies [an administrative body of the British Empire]. Hundreds of other plaques, alongside thousands of bronze sculptures, carved ivory tusks, and many other sacred and royal art works, were simply stolen by officers, soldiers, sailors, administrators, traders, and others present at the military attack, and then haphazardly sold for private gain or passed down across generations. German, British and other European museums quickly bought what they could on the open market. And then, within weeks of the destruction of Benin City, the Bronzes came to be displayed in museums from Berlin and Leipzig to London and Oxford.

The role of Victorian anthropology’s use of museums as devices to produce myths came into focus: myths of “cultural superiority” that chimed with the “race science” of anthropology at that time. I realised that the Bronzes were far from some marginal side-effect of empire. They were memorials to a desecration that paved the way for the creation of colonial Nigeria, trophies of war that were used to exhibit a story of cultural supremacy. The ancient African kingdom of Benin was destroyed with Maxim machine guns, rocket launchers and Martini–Enfield rifles, but that destruction was naturalised, and made to last, through museum displays. As the book argues, the museum galleries and vitrines came themselves to be used as a unique type of weapon.

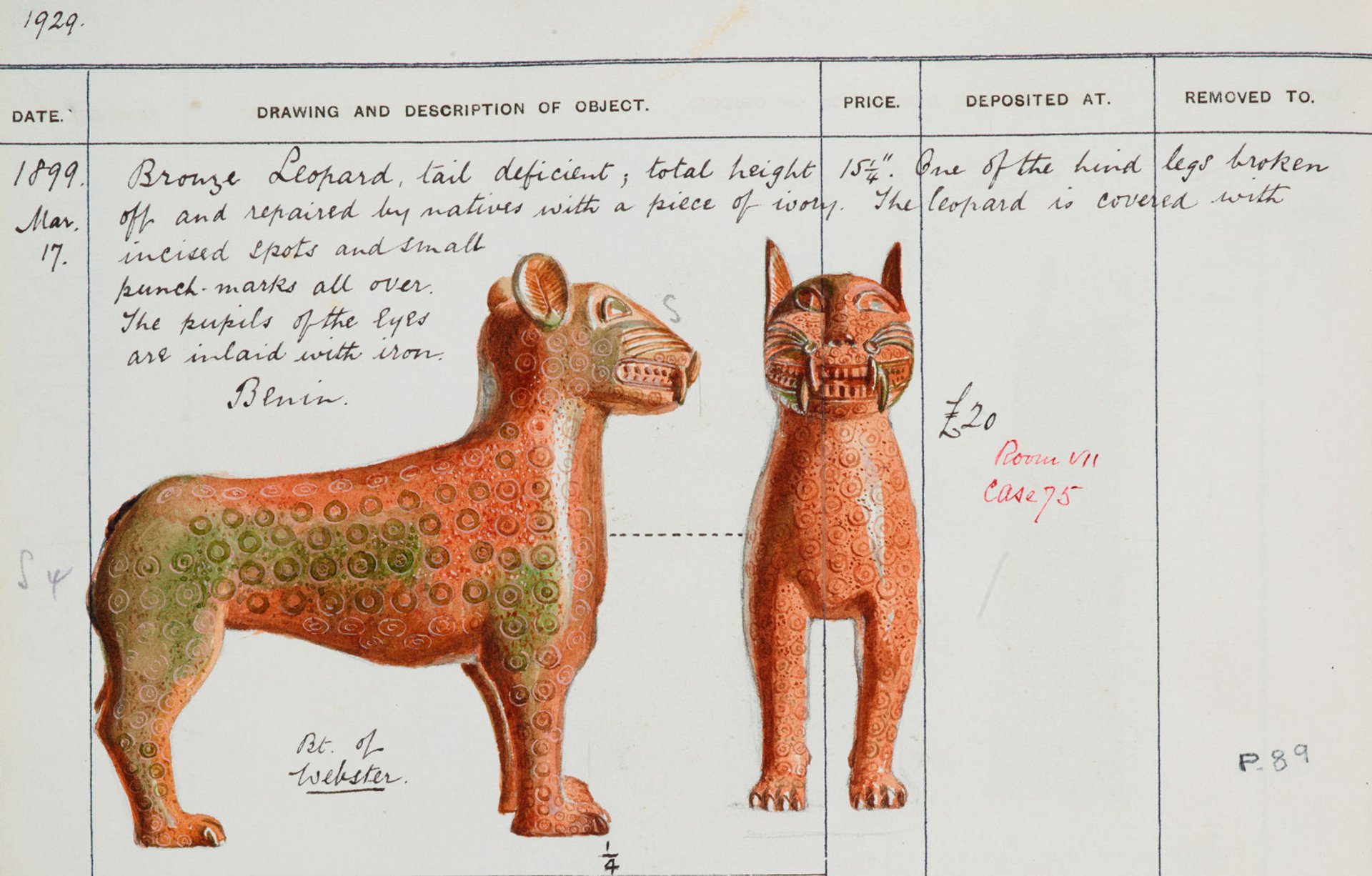

A page from the illustrated catalogue of the Pitt-Rivers Museum, which was in Farnham. The image shows a brass leopard that is now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York

Do you expect institutions to act on your recommendations in any way?

We’ve never needed world culture museums more —with all their potential to shift our understanding of art beyond a Eurocentric lens—than we do in this present moment. But The Brutish Museums traces how anthropologists’ use of the Bronzes as memorials to dispossession, as white supremacist propaganda, continues to this day, and will do for as long as they remain on display in museums like the Pitt Rivers. Dismantling, re-imagining and re-purposing this outdated racist infrastructure is an urgent task if we’re going to rebuild world culture museums that are fit for the 21st century.

How can we achieve that? Well one important step is to decentre the loudest, richest and most powerful institutions as we listen to African calls for returns. People think the Benin Bronzes are all in the British Museum. But in reality, that collection of perhaps only 900 objects (no specific number is available) represents less than 10% of what was looted in 1897. Each of the 160 or more museums around the world that hold objects taken from Benin in 1897—45 in the UK alone, 38 in the USA, and so on—will have a different process for deciding to return looted African art.

Trustee bodies, museum boards, and their audiences, stakeholders and communities all have a role to play in moving African restitution from just dialogue to action. The book’s appendix presents a first attempt at listing those museum collections, from Berlin to Manchester, St Petersburg to Detroit, Madrid to Abu Dhabi, Zürich to Amsterdam.

With pressure growing around the restitution of works to Africa, could your book be a tipping point?

The tipping point is definitely here, but it’s being created by African colleagues. We should remember that restitution is an African movement, and the first returns to Benin were made in 1938 when two sacred royal coral crowns were returned to the Oba (king) of Benin from the British Museum. Today, my role as a curator at a museum that currently cares for 150 of the stolen Benin objects is to listen to and amplify the ongoing demands for returns to the royal court of Benin, to share knowledge of the range and nature of Benin objects in museums around the world, and to start to take stock of how European museums’ continued possession of stolen artworks serves to make the violence and racism with which they were taken persist into the present.

It’s through the unfinished nature of these historical events that we must understand contemporary requests for restitution. It’s a shock to learn that so many Euro-American museums are still variously unwilling and unable to publish lists of what looted African art they hold. Openness about what precisely is held, and where, is an urgent first step. As I have tried to show with the case of the Benin Bronzes, the onus for generating this basic factual information must lie with museum curators, not with any potential claimant. Above anything it’s by facing up to the intertwined histories of colonial violence and Euro-American collections of African art, and by taking action on cultural restitution on a case by case basis, that the brutishness of our museums can be consigned to history.

• The Brutish Museums: The Benin Bronzes, Colonial Violence and Cultural Restitution, Dan Hicks, Pluto Press, 336pp, £20.00 (hb), published in November