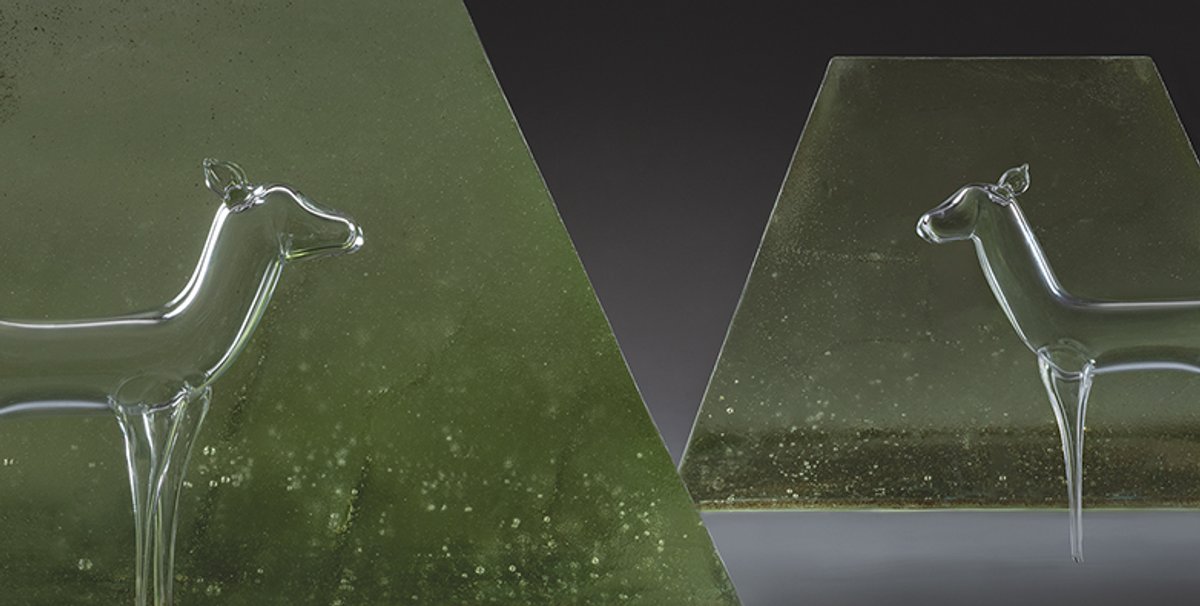

Melting moments: glass production at Berengo Studio, in Murano, Italy. The studio has worked with the designer Andrea Mancuso to produce a series of champagne glasses for Design Miami Courtesy of Berengo Studio

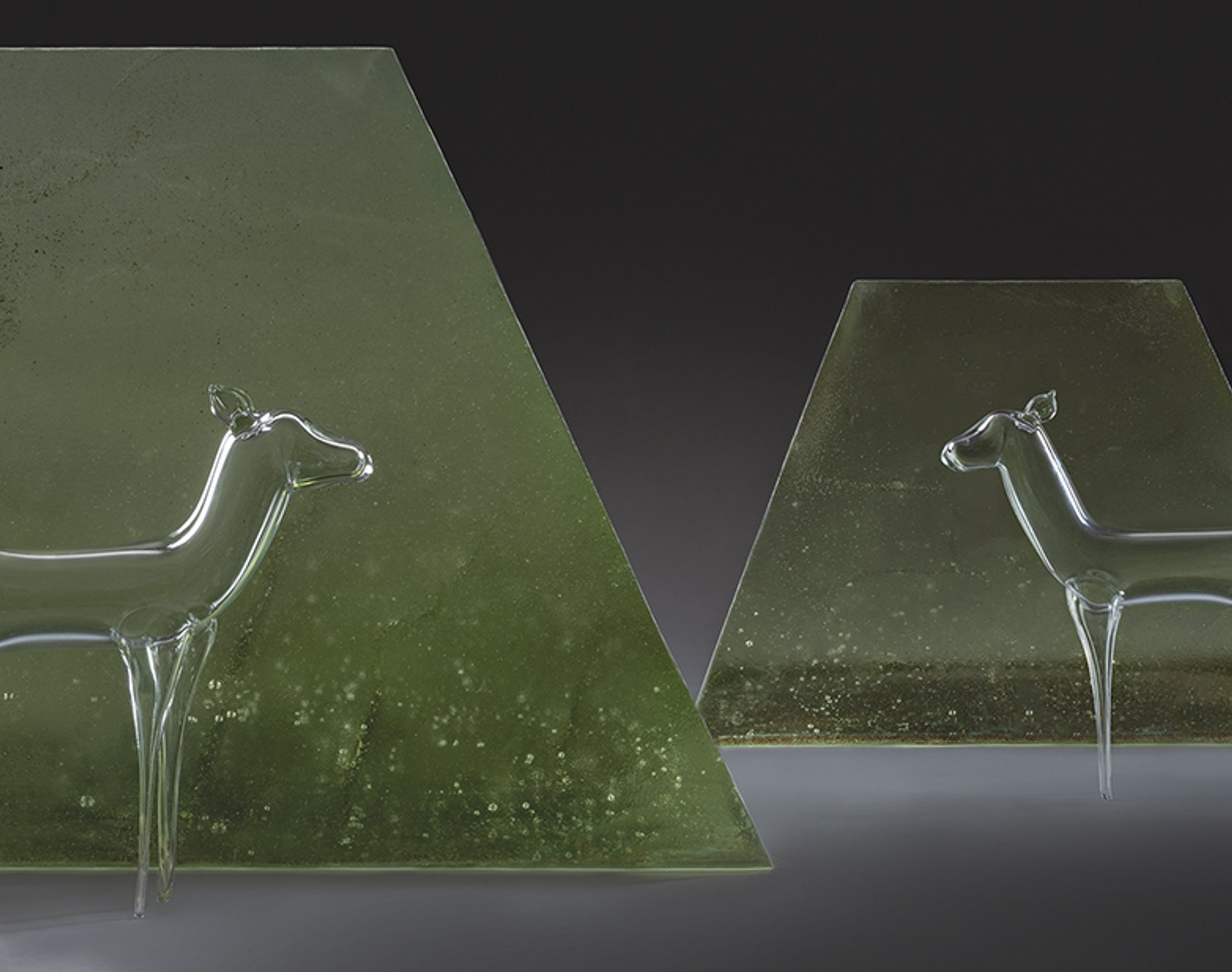

Robert Wilson is a surprising presence at the 15th edition of the Design Miami fair. Admittedly, the 78-year-old American’s artistic practice is a broad one, running the gamut from theatre and spectacle to sculpture and film. But who knew it would one day lead to this silicon wonderland—an exquisite installation of delicate glass deer that meander through a landscape of chunky glass truncated pyramids.

“I see all of my work as one thing,” says Wilson, whose installation A Boy From Texas (2019) is being shown at Cristina Grajales Gallery’s stand, in co-operation with Paul Cooper Gallery. “Proust said he was always writing the same novel. Cézanne said he was always painting the same still-life,” Wilson says. Although this time, for Wilson, it is very personal. “The exhibition [at Design Miami] relates to my childhood. From an early age I was taken deer hunting by my father, but I never wanted to shoot anything.” Instead, Wilson, who grew up in Waco, Texas in the 1950s and 60s, developed a deep love of deer and of the silence of the forest. “I could sit alone for the entire day,” he says. Now this atmospheric piece, created with glass experts at the Corning Museum of Glass in New York state, pays homage to their beauty—the glass suggesting the inherent fragility of a deer’s streamlined form, and perhaps Wilson’s own adolescent self. “I like how quiet the deer are, how they listen and walk and the beauty of watching them in stillness, and leaping.”

It makes sense for an artist like Wilson, who is deeply concerned with light, to be drawn to glass with its refractive qualities and capacity to be both transparent and opaque. Elsewhere at the fair, visitors will find the material being used as a medium of expression by an increasing number of artists. “The possibilities for glass are endless,” says Zesty Meyers of the New York gallery R & Company. “Reflection, transparency, translucency all have meanings. So although it is a craft material, I now see people using it to express other ideas.”

“A beautiful object deserves the same attention as a beautiful work of art”

Meyers was a glass-blower himself, and has worked for many years with Jeff Zimmerman, an artist who uses master craftsmanship to elaborate his conceptual thinking through organic shapes made with pushing, pulling, dripping and spinning actions. In 1991, Meyers, Zimmerman and R & Company co-founder Evan Snyderman set up the B Team, a group of artists that, for seven years, travelled around the US demonstrating the performative qualities of glass-blowing. “We’d make it rain molten glass,” Meyers says. “We’d walk on molten glass.” The growing interest in the medium can also be seen by the popularity of Blown Away, a Canadian glass-blowing competition recently shown in ten episodes on Netflix.

Thaddeus Wolfe’s molten, multi-coloured Untitled (2019) at Pierre Marie Giraud’s stand at Design Miami Courtesy of Pierre Marie Giraud

Meyers and Snyderman are showing Zimmerman’s work at Design Miami as a walk-through installation of clear glass and white filigree forms, also created at the Corning museum, assisted by the technical genius of James Mongrain, who has long headed up the workshop of US glass sculptor Dale Chihuly.

“Jeff’s work is not functional,” Meyers explains. “I guess you could put something in his crumpled vases, but they’re really about capturing the fluidity of the material and the imperfections of nature.” He is also one of the gallery’s most successful artists, with private commissions all around the world. The art dealer Dominique Lévy has a dazzling Zimmerman work in her New York flat, while Sean Kelly has a permanent piece in his Manhattan library space.

David Alhadeff, the founder of design gallery The Future Perfect, which has spaces in New York, San Francisco and Los Angeles, agrees that a new interest in glass on the part of collectors is due to the unexpected works that artists are producing. “It’s a relatively humble material,” he says, “that upon manipulation carries the artistic vision of the maker.” Alhadeff works with John Hogan, who grew up next to a glass studio in Toledo, Ohio, and is now based in Seattle. Hogan’s mission is an exploration of light and colour, carried out in small, scintillating and seductive forms that are deliberately hard to define.

“Light is energy,” says Hogan, who is inspired by the molecular gastronomers, Ferran Adrià and Grant Achatz. “Because of them, I realised I could approach material research with systematic experimentation. By assuming nothing about processes I haven’t seen or tried, I’m able to discover new things.” Among these are alternative, and original, ways for glass to carry colour.

Robert Wilson’s A Boy From Texas (2019), above, at Cristina Grajales Gallery’s stand, was inspired by the artist’s childhood in rural Texas Courtesy of Cristina Grajales Gallery, Robert Wilson and Corning Museum of Glass. Hogan:

As with all craft practice, there is always the danger that the observance of its traditions and skills can lead to a stagnation of creativity. From the 1970s onwards, this happened in the high home of glass, Murano. But gradually an influx of artists brought about significant change to the island off Venice. In 1989, Adriano Berengo established a studio there and since 2009 he has invited contemporary artists, including Ai Weiwei and Laure Prouvost, to push his master practitioners to come up with complex new solutions to achieve their ideas.

This year Berengo’s studio has also helped produce a series of champagne glasses designed by the Italian designer Andrea Mancuso for Perrier-Jouet, which can be seen at Design Miami. “I started with sketches, then plasticine models,” Mancuso says. “Then we moved onto 3D printing. It was the technology that allowed me to create some complex shapes that somehow express the delicacy and fragility of nature.”

Other artists, such as Ritsue Mishima, have been drawn to Murano for both its tradition and endless potential. Now she travels regularly between Kyoto and Venice. “She has four people [in Venice], each with a certain talent,” says Pierre Marie Giraud, who set up his eponymous gallery in Brussels 15 years ago. “But by working with her, they have to develop their abilities even more.” Giraud describes the artist as having a similar role to a conductor or a chef. “Glass artists like Ritsue are there to guide and oversee these experts. And everyone is learning all the time.”

John Hogan’s Glass Water Lens at the stand of The Future Perfect © Amanda Ringstad; courtesy of The Future Perfect

Giraud had intended to focus on ceramics when he first started his gallery but says he “couldn’t resist” showing Ritsue, who he describes as being “the most interesting voice in her field at the time”. He says: “I am devoted to her, but she only makes 30 pieces a year. It’s a small production.” Even so, her works sell for a relatively modest €20,000 to €25,000.

This year, Giraud is presenting other glass artists at Design Miami, including Brooklyn-based Thaddeus Wolfe. While Mishima’s work has the fragility of spun sugar and the vibrancy of a leaf blowing in the wind, Wolfe’s is architectural, Brutalist even. He does his own blowing, into structured moulds, and plays with pigment. The angular results flirt with Constructivist and Cubist geometries.

Giraud’s problem now is obtaining enough work from his artists. For example, another Japanese artist he represents, Yoichi Ohira, has only around 600 pieces in existence. As fairs such as Art Basel and Design Miami have created stronger cross-dialogues between art and objects, collectors are once again acquiring the decorative arts alongside paintings and sculptures, rather than working in a self-imposed collecting silo. “A beautiful object deserves the same attention as a beautiful work of art,” Giraud says. “And people are coming back around to a broader way of thinking”—and that includes glass.