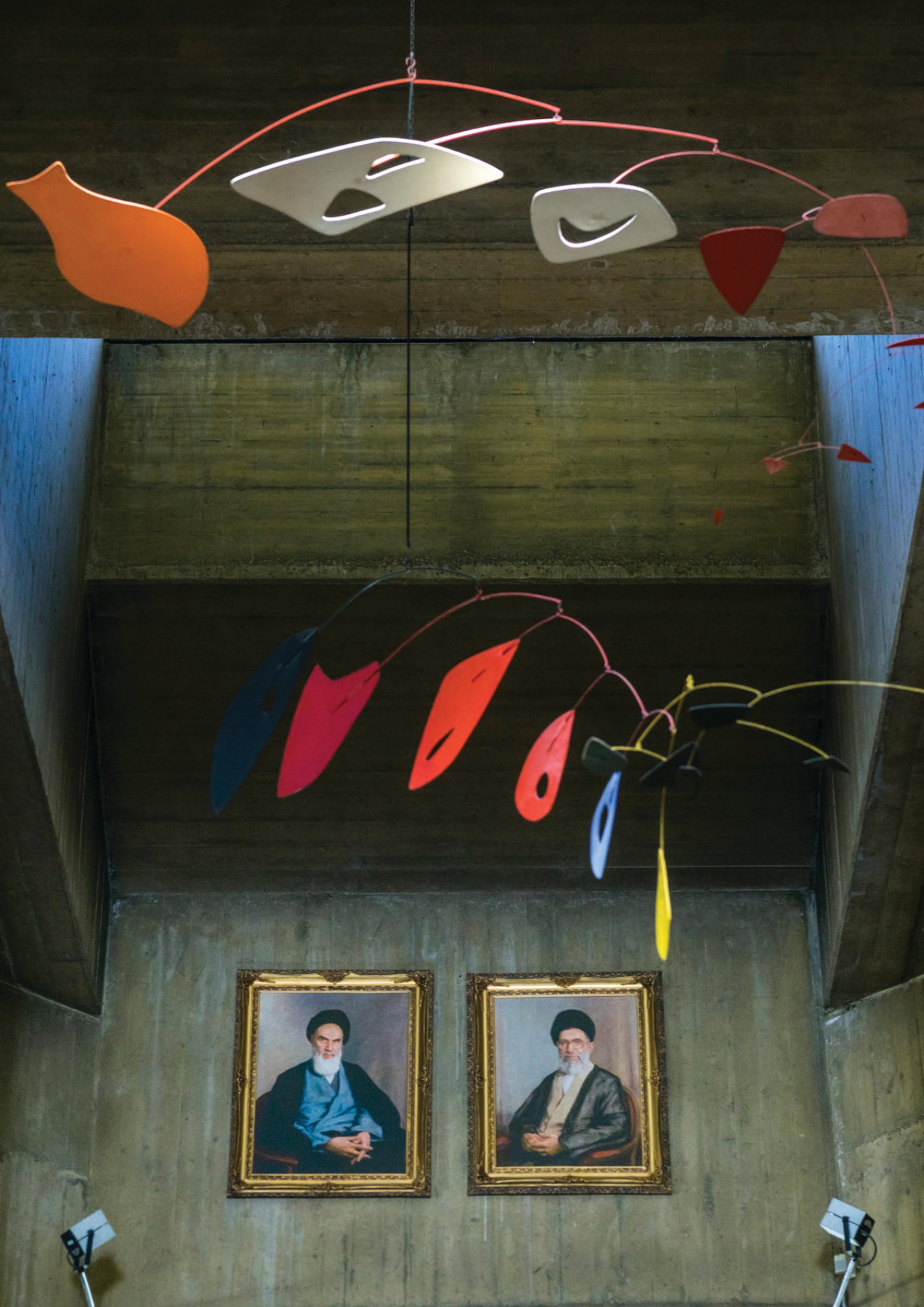

The Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art (TMoCA) recently opened Farideh Lashai: Towards the Ineffable (until 26 February), a retrospective of the work of the Iranian Modern artist—and this is no ordinary show. It has been co-organised by the Italian super-curator Germano Celant, along with the Iranian curator Faryar Javaherian, and it intersperses the late artist’s work with masterpieces of Western Modern art collected by the museum before the Islamic Revolution of 1979. The vernissage mixed East and West, too: Ali Jannati, the Iranian minister of culture, was there, along with the biggest gathering of overseas visitors to the museum since the revolution.

The latest in a series of events demonstrating Iran’s growing presence on the international art scene, it reflects not just the opening-up of the country and of the capital’s famed Modern art collection, but also the growing reputations of Iranian artists in and outside their native country.

Last February, the Davis Museum at Wellesley College in Massachusetts had a retrospective of the sculptor Parviz Tanavoli and, in March, Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian had a show at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York—the first such presentations of these Iranian Modernists on US soil. Both artists also featured in the Iranian pavilion at last year’s Venice Biennale, while in November, the Contemporary Istanbul art fair had a section dedicated to the art of Tehran.

The most striking moment came in October, in the shape of a deal between the Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation and TMoCA to send 60 Western works from the Iranian museum to Berlin. Majid Mollanoroozi, the Tehran museum’s director, made reaching out to German institutions his top priority when he took the job two years ago. “I have talked to many directors of German museums and initiated discussions with those in Frankfurt. Now we have made an agreement with Berlin,” he says.

An official close to TMoCA tells us that the institution is asking for $3m and will use the funds to restore the museum as well as its holdings. Mollanoroozi acknowledges the need for restoration and says that money from ticket sales will be dedicated to this.

The works destined for Berlin have not been confirmed, but they include pieces by Francis Bacon, Willem de Kooning, Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko and Andy Warhol. They were bought in the 1970s under the patronage of former empress Farah Pahlavi, who commissioned her cousin, Kamran Diba, to design the museum. Asked if TMoCA will send works such as Renoir’s Gabrielle with Open Blouse (1907), which is problematic for some Iranians because it features nudity, Mollanoroozi says: “We have 1,500 works and can easily choose between them. We don’t need to choose the sensitive ones that may cause problems.”

Increased professionalism More evidence of TMoCA’s renaissance is its role as the commissioner of Iran’s pavilion in Venice, a first for the Tehran institution. “It’s returned to its professionalism, and it’s important for us to maintain this,” Mollanoroozi says.

There are worse ways to advertise these credentials than to bring in one of the West’s most famous curators. Celant, the first non-Iranian curator to put on such an exhibition, was suggested by Maneli Keykavoussi, Lashai’s daughter. Mollanoroozi had seen the Italian’s exhibition at the Milan Expo and was delighted by the prospect, suggested by Celant’s co-curator Javaherian, of infusing the Lashai retrospective with Western and Iranian works from TMoCA’s holdings. “In this exhibition, we want to introduce Iranian art first, then the collection and then the museum,” he says. “Those who are against Iran say that some masterpieces have been destroyed or are fake. In showing these works, we will confirm that they are all OK.”

The show is a new dawn for Lashai, whose presence in a state-run institution has raised eyebrows. She was jailed in the 1970s for her leftist beliefs, and has painted Mohammad Mossadegh, the democratically elected prime minister deposed in a 1953 US- and UK-supported coup for attempting to nationalise Iran’s oil industry.

The exhibition’s early development was not without complications. “These people are Islamic, and Farideh had a political background,” says Javaherian, the show’s co-curator. “First, they said they wouldn’t give me the whole museum. It was all about negotiation and compromise, but, little by little, they accepted.” Mollanoroozi dismisses the leftist beliefs that led to Lashai’s imprisonment—those opinions and events happened before the revolution, he says. “In the world of politics, she wasn’t famous, but in art she was.”

Mollanoroozi confirms that TMoCA has not contributed financially to the exhibition, which has reportedly cost the Lashai Foundation between $200,000 and $300,000, plus $30,000 from the show’s sponsor, the Iran Tourism Bank. No private galleries have helped to fund the exhibition. Maneli Keykavoussi says that Celant waived his fees, which are not inconsiderable—he and his team received €750,000 for the Milan Expo, as The Art Newspaper revealed in 2014. But an official close to both the Lashai Foundation and TMoCA says that the museum is in talks to lend its Western collection to the Prada Foundation, of which Celant is the director. It seems unlikely, then, that the fee paid by the Prada Foundation will match the Berlin museums’ $3m outlay. It would not be the first collaboration between a Tehran-based institution and the Prada Foundation: in May, a work from the National Museum in Tehran appeared in Serial Classic, the Foundation’s show of Greek and Roman sculpture.

Negotiations with US museums are not so advanced. Mollanoroozi has met Melissa Chiu, the director of the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden in Washington, DC, about potentially lending works. Chiu’s interest began while she was the director of the Asia Society in New York, which staged the show Iran Modern in 2013. “I had begun discussions earlier on and continued discussions when I moved to the Hirshhorn,” she says. “I’ve been to Iran a number of times and became familiar with the TMoCA collection.”

The Berlin deal emerged through government-to-government discussions, but US-Iran talks are not yet at that level. Convincing reports predict that no deal will be struck because of the opposition of the US Defense Intelligence Agency, which blames an Iranian government official for bringing down a US Boeing 747 jumbo jet over Lockerbie in Scotland in 1988. “It’s true to say that it is an issue and we are in private conversations with the State Department,” Chiu says.

But what of the art scene beyond the museum? Six months after the announcement of diplomatic agreements that will ultimately lift the Western sanctions on Iran, the country’s changes on an international level are profound. But in Tehran, the art scene has been buoyant for some time—so much so that some wonder whether the removal of sanctions is needed to boost it further.

For art enthusiasts in Tehran, Friday evening is a gallery-hopping, see-and-be-seen parade among the city’s burgeoning cultural spaces. One newcomer is Dastan’s Basement, founded by Western-educated Hormoz Hematian. In 2012, he established his gallery in Fereshteh, an upmarket district that has other galleries. “I wanted to see art of my generation. The neighbourhood required the art to be upscale and we wanted to be otherwise,” he says. “Dastan is my favourite hero in the Shahnameh [Book of Kings], and in Persian, it also means ‘several hands’, denoting the fact that this is a group effort and therefore a democracy.”

Dastan’s Basement, which presents the work of emerging artists, priced between $100 and $3,000, is a go-to destination for Tehran’s young, aspiring collectors. “We’re consistently hitting 250-plus visitors [to openings], and have hit as high as 650 and 720 in a four-hour period in this 90 sq. m basement,” Hematian says. In November, he launched Dastan +2, a 180 sq. m space on the second floor of a nearby building, where works by established Iranian artists are on sale, priced between $800 and $150,000. “The art scene was doing what it was doing with or without the sanctions,” he says, adding that their removal will make transacting easier. Although the gallery has participated in international art fairs, selling work to “80% foreign buyers”, many transactions are not concluded due to the restrictions on Iranian banks. “Imagine this being resolved,” he says.

Ali Reza Sami Azar, the former director of TMoCA and now a professor of post-war art at the Mahe-Mehr Institute in Tehran, says: “Easier transactions also mean a demand for Iranian art that can be exported.” Azar put on the first show of TMoCA’s Western works in 2005, and conceived Tehran Auctions in 2011 to fund his publication Art Tomorrow; the first sale of Iranian art made $1m, and the auction is now an annual event.

“There is a new generation of young collectors whose rich parents collected antiquities,” Azar says. “These kids are Western-educated and prefer contemporary art. One of the reasons Tehran Auctions has done so well is the sanctions, because transferring money is difficult, plus inflation made art very expensive when you want to buy in dollars rather than Iranian riyals.”

The Iranian collector Mana Mobargha, who has amassed more than 600 works of Modern and contemporary Iranian art with her husband, Nader, agrees that the lifting of sanctions will ease transactions and “open the door to Iran’s market for international collectors and Iranians abroad”. They lent works to the Tanavoli show at the Davis Museum as well as the Iran pavilion in Venice. Based mainly in Baku and Vancouver, they intend to build a museum for their collection in Canada.

It is exactly the kind of initiative that concerns the Iranian artist Farhad Ahrarnia. Based in Sheffield, in the UK, and Shiraz, in Iran, he believes that “artists in Iran need more funding and commitment from institutions, both public and private, to record and reflect on their works critically”. Ahrarnia, who shows with the Dubai-based gallery Lawrie Shabibi, places more importance on the intellectual than the commercial importance of art. “We are all aware of how damaging the effects of speculation can be,” he says. “It leaves many artists’ livelihood in crisis when the excitement of a market is over.”

Believe the hype? The Iranian artist Nazgol Ansarinia says: “I hope that, as the art community becomes internationally more active, it also becomes aware of its strengths and shortcomings, and has the patience to learn, take things step by step and not try to compensate overnight for the lost time.”

At a sale at Sotheby’s in London last December, a canvas by the late Iranian Modernist Behjat Sadr sold for £56,250, an auction record for the artist. Speculators quickly tried to generate hype around Iranian art, and although predictions of a boom are premature, business is thriving in Tehran. As we revealed last month, TMoCA will stage a show dedicated to the Belgian artist Wim Delvoye in March, while collectors’ trips to the city are being planned, institutions and publishers are knocking on Mollanoroozi’s door and Azar is working towards an art fair in the Iranian capital next autumn. “The Tehran Art Fair will be a clear sign of a post-sanctions era, with more relaxed socio-cultural circumstances as a result,” he says.

Azar’s positivity is understandable, but Iranians exemplified resilience and self-sufficiency for years before the recent thaw in relations with the West. As Farhad Ahrarnia says, it is a “myth that Iran was entirely shut off from the rest of the world behind an iron curtain”. A sanctions-free Tehran art scene should indeed see renewed support and appreciation for art, but it has been there quietly for decades, away from Western eyes.