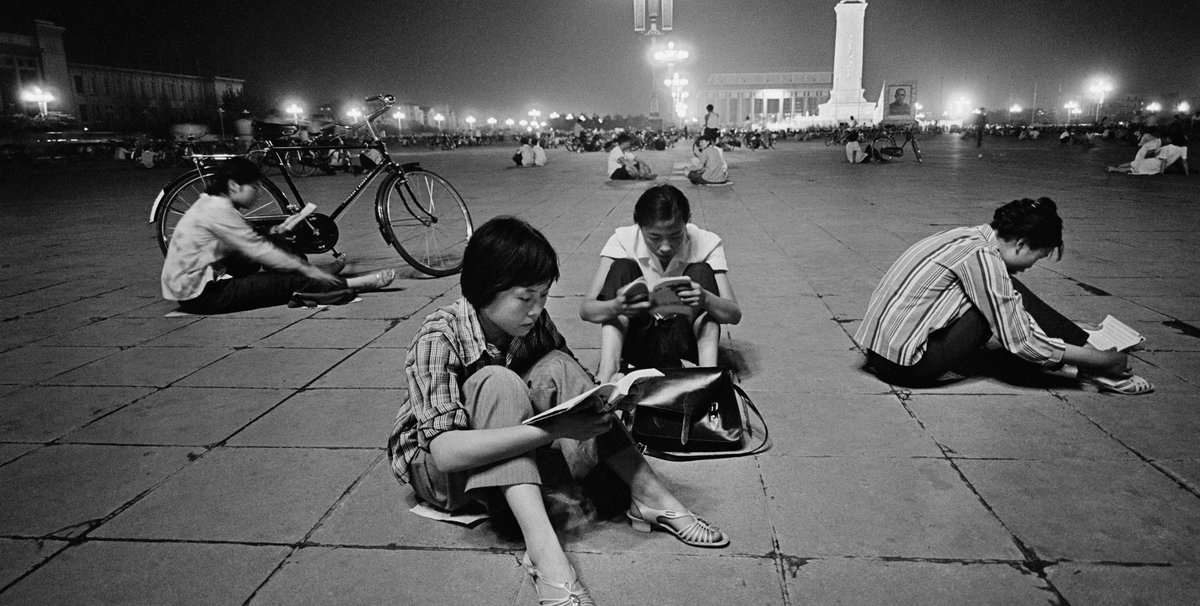

The great portrait of Mao Zedong looked out over a sea of tents. Punk bands performed. Freedom flags fluttered in the wind. Public buses were commandeered, covered in slogans and used as meeting places for the demonstrations. A torch-holding sculpture crafted from Styrofoam was erected. They called her The Goddess of Democracy. The crowds kept coming until Tiananmen Square overflowed.

In 1949, Chairman Mao had used the square, which lies at the heart of the Ming Dynasty’s Forbidden City in the centre of Beijing, to announce the People’s Republic of China. “I knew the Chinese Communists would never tolerate such symbols of the West staring at Mao,” the Hong Kong-born photojournalist Liu Heung Shing says of the activities on the square.

Few people can claim to understand Tiananmen Square like Liu. He was present from the first day of the protests, which began on 15 April 1989. Western journalists turned up but tired of the event and returned to their bureaus. Liu stayed and was in the square every day until the bloody dénouement on 4 June when the Chinese military advanced and hundreds, if not thousands, of unarmed protesters were killed.

A sweeping monograph of Liu’s work is now being published by Steidl. The publication launches at Art Basel in Hong Kong—just two weeks before the 30th anniversary of the Tiananmen Square protests.

Liu was raised on the mainland in Fuzhou province before moving to New York at the age of 16. After excelling in a photography course at college, he gained work as a staff photographer at Time magazine. He was only 25 when Chairman Mao died, but as a Chinese passport holder and native speaker he was assigned as Time’s foreign correspondent in Beijing.

Liu returned to China in 1976. He has photographed the country ever since, documenting the days after Chairman Mao’s death through to the economic boom of the present era.

Liu’s book is titled A Life in a Sea of Red, a reference to the Chinese proverb “alive in the bitter sea”, which alludes to the virtue of perseverance in tumultuous times. The central chapter of the book is dedicated to the events of 4 June 1989. He worked closely with the Associated Press photographer Jeff Widener that day, and in the midst of countless military personnel was instrumental in safely getting the iconic Tank Man image “on to the wires” in the pre-digital age. The stakes were high: the Chinese troops were reportedly using cattle prods to convince Western photographers to give up their equipment.

A Chinese couple on a bicycle take cover at an underpass in east Beijing as tanks deploy overhead, 5 June 1989 © Liu Heung Shing/AP Photo

“I told Jeff to travel from the diplomatic compound to the Beijing Hotel, which is on the edge of Tiananmen Square, by hitchhiking on the back of a cyclist with his camera hidden,” Liu says. “Two hours later, he called me and said he had a photo of a man standing in front of a tank. I said: ‘Uh-oh.’ I didn’t know what the picture looked like, but I told him to take the film from the camera, go to the hotel lobby and convince a Western student to bring me the canister.

“A young American student in blonde pigtails turned up and asked for me at the compound. She had the film in her backpack. We processed it straight away and sent it to New York. As soon as the picture cleared the wire, the phone rang, and a Canadian journalist said: ‘The tanks are going your way.’ I ran up to the rooftop and saw the tanks coming. Right away I saw a young couple—a pair of lovers—under the bridge.”

Liu captured the two lovers embracing in fear in the underpass. They were looking up as two tanks rumbled over the bridge above. Liu’s lovers under the bridge and Widener’s Tank Man ran in tandem across the front covers of the world’s newspapers the next day.

Officially, the protests won’t be memorialised at all. It’s a stain on the party leadership they can’t acknowledgeIan Johnson, Pulitzer prize-winning reporter

But Liu’s images have never been seen in China. Indeed, if one were to visit Tiananmen Square in Beijing on 15 April this year, one will probably discover a city carrying on as if it were just another day. “The government will go out of its way to make sure there’s no recognition,” Liu says.

Ever since the events of 1989, the Chinese state has officially cleaved to an Orwellian line—that the protests were a riotous “counter-revolutionary” insurrection. Most Chinese citizens born after the event have only the haziest idea of what happened. “Officially, the protests won’t be memorialised at all,” says Ian Johnson, a Pulitzer prize-winning reporter for publications including the New York Times, who is based in Beijing. “It’s a stain on the party leadership they can’t acknowledge. Instead, they’ve constructed a counter-narrative—that the military intervention was unfortunate but caused by chaos, and the victims were mostly soldiers.”

The aggressive suppression of any documentary images of the event allows for this warping of fact. “This government in particular is known to edit history to suit their version,” Liu says.

In 2015, Liu founded the Shanghai Center of Photography, one of the largest exhibition spaces dedicated to photography in China. What would happen if he ever tried to exhibit his documentary images there? “It would be impossible to exhibit the work,” Johnson says. “It would be hard even to print the photographs. If they asked a printer to process the images, they would either refuse or alert the authorities. His gallery would be shuttered, and he would never be able to do business in China again.”

Worse yet could happen. In December 2018, the renowned Chinese photojournalist Lu Guang, a former World Press Photo winner, was detained for unconfirmed reasons while working in Xinjiang, a remote, semi-autonomous territory in northwest China. He remains incarcerated.

Sim Chi Yin is a photographer, doctoral researcher and current nominee member of Magnum Photos. She shares her time between London and Beijing, where she previously worked as a documentary photographer. “The screws have been put on Chinese civil society,” she says. “The civic space within the political realm, the media and society at large has been restricted over the past five years. There’s been a general clampdown on photojournalism, but it has happened in the context of a broader clampdown: on writing, documentary filmmaking, speaking engagements—anything that reflects the reality of Chinese society today. It’s across the board.”

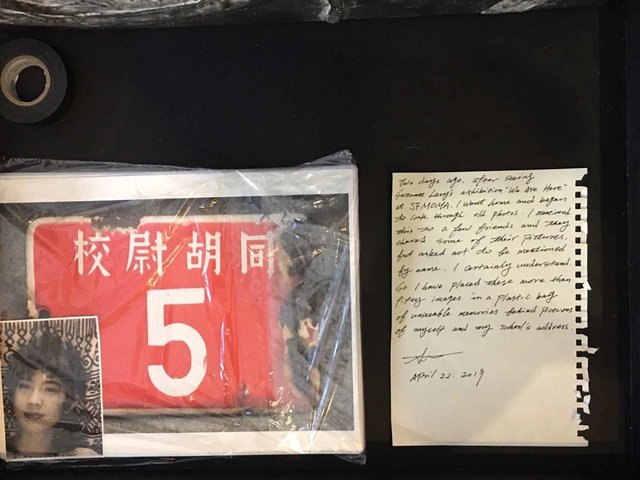

The controls wielded by China’s ruling party are highly effective, Sim says. “Some intellectuals, and the people whose relatives or children died in 1989, might attempt to memorialise Tiananmen Square in their own ways,” she says. “But the security apparatus is so efficient that nothing will ever happen in public. People will try to remember those they lost. But you can’t even lay flowers on the streets or you will be bundled away. You have to live in China to really know it.”

Yet an underground form of civic remembrance does exist. “The people who participated in 1989 are widely around,” Liu says. “They will tell their children. But those children don’t have any visual references to go by.”

There are no plans to stock mainland China with copies of A Sea in a Life of Red. “But someone will come to Hong Kong and return with the book in their suitcase,” Liu says. “Censorship in China today is never airtight. It never has been, and it never will be.”

• At Art Basel in Hong Kong, Life in a Sea of Red is available at Kelly & Walsh’s stand; Liu’s works are on STAR Gallery’s stand