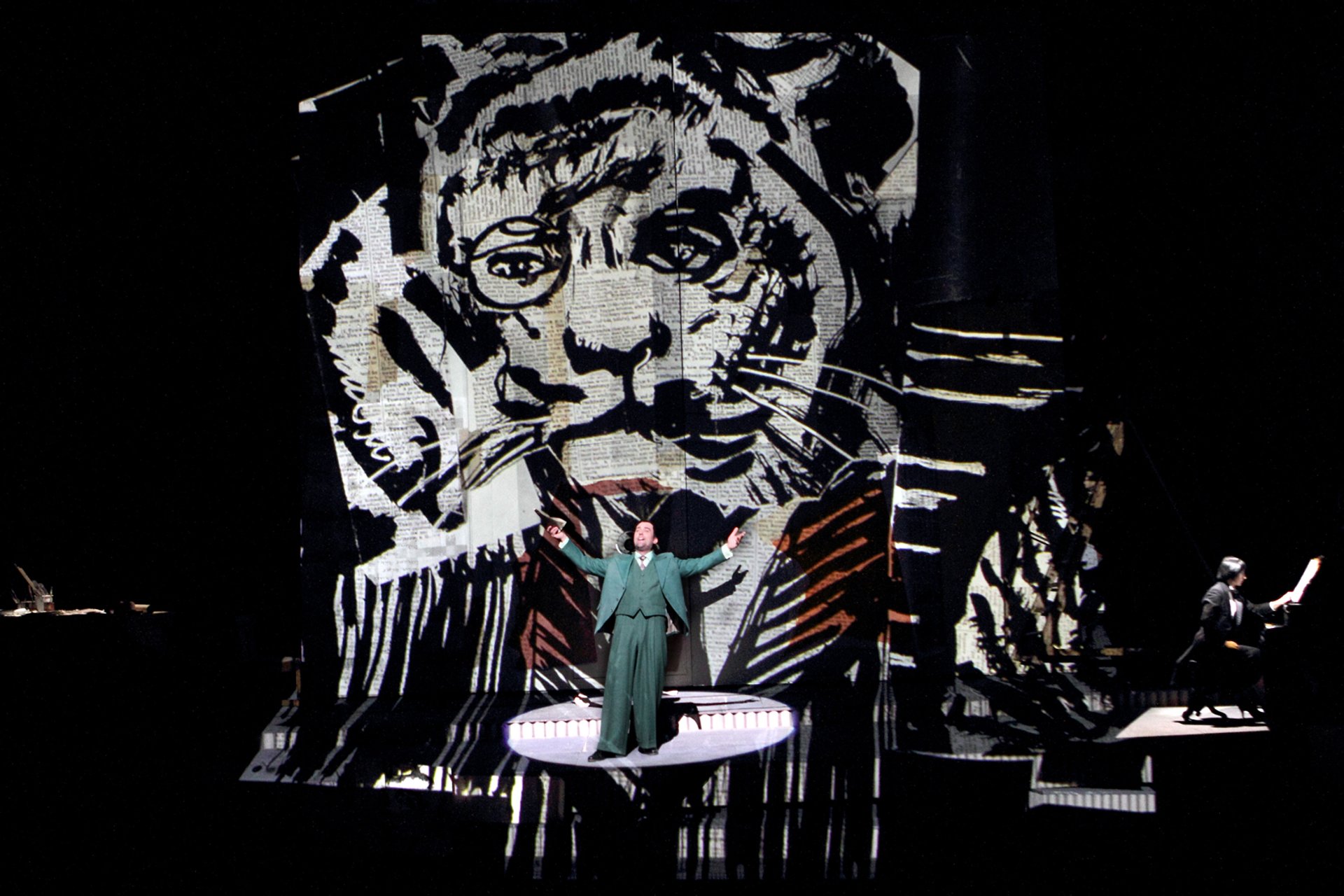

Marina Abramovic in The Seven Deaths of Maria Callas at the Munich Nationaltheater © Wilfried Hösl

As Covid-19 lays waste to exhibition openings and opera premieres, one light from astride both worlds shines in the darkness. The ever-provocative Marina Abramovic cocks a snook at even a global pandemic. She had been commissioned by some of the most famous opera houses in the world to create and perform in an operatic production of her own devising called The Seven Deaths of Maria Callas. A lone survivor in the world of operatic first nights—according to some, now the most dangerous art form of all, with its high risk of viral transmission due to the rather integral element of singing—The Seven Deaths opened in Munich on 3 September to an audience of 500 spaced out in the 2,300-seat Nationaltheater. It is interesting to imagine which section of the Munich audience was more outraged: those who were furious at this controversial figure being given free rein at one of the grandest temples of German high art, or those whose tickets were cancelled as a result of social distancing and had to satisfy themselves with the livestream.

But what motivates a visual artist to participate in an opera production? This unwieldy art form, which requires the designer to work within a traditional hierarchic production structure, often involves hundreds of performers, an enormous logistics operation and a good deal of compromise from everyone involved. At first glance this would seem anathema to an artist who works essentially alone with total authority over their work, outside the restrictions of an institution and in control of their own timeframe. Daniel Kramer, the former artistic director of the English National Opera (ENO), says that for artists, “it all begins with the music”. Kramer has enjoyed collaborations with several artists including Anish Kapoor. The curator Norman Rosenthal—equally expert in opera as art—concurs: David Hockney, whose series of productions for the Glyndebourne Festival Opera and the San Francisco Opera established him as a major stage designer alongside his status as a star artist, was “really capable of listening to the music”. Hockney’s final opera production was Puccini’s Turandot for Chicago and San Francisco in 1992/3. He had started to lose his hearing by then, and with it, his access to the art form.

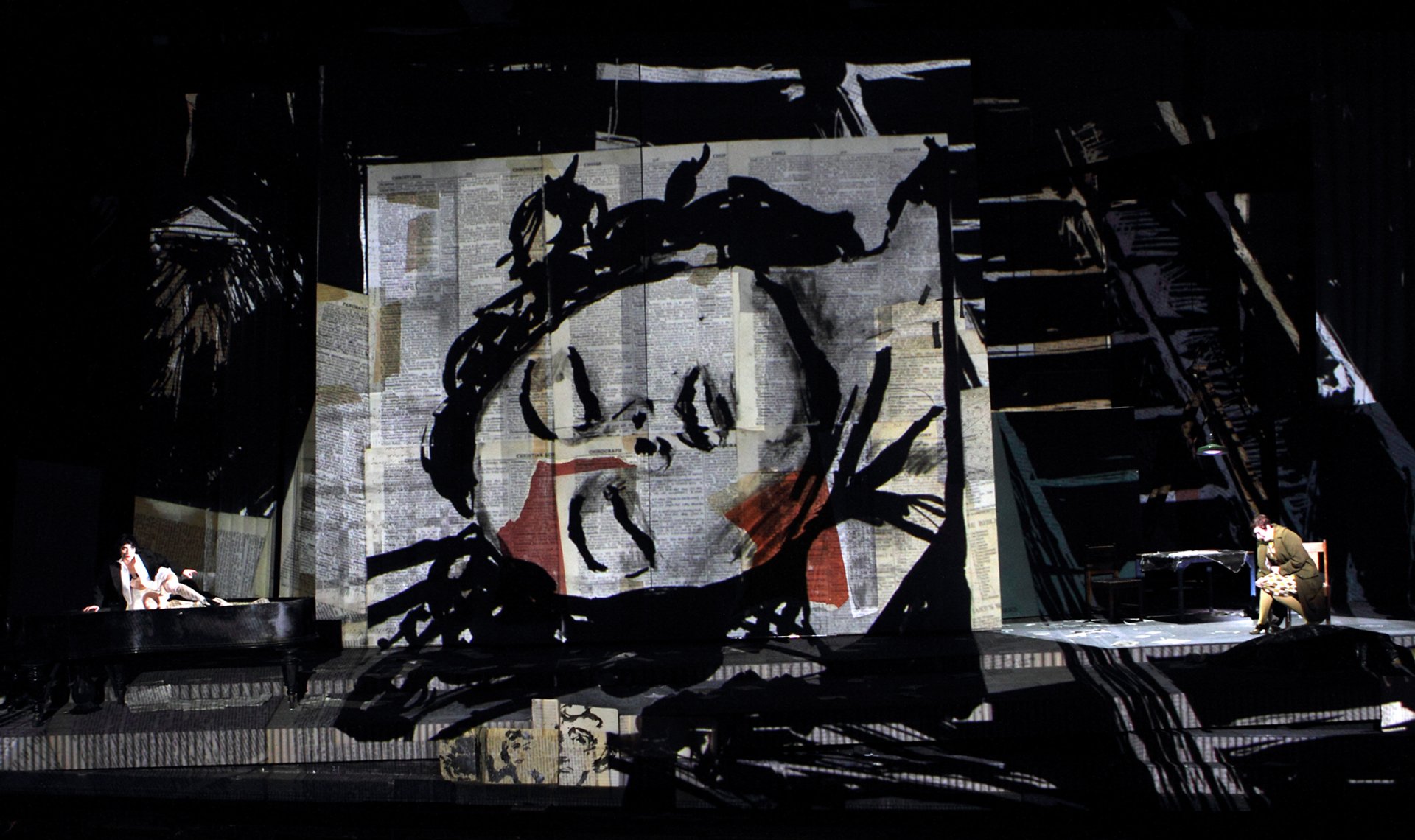

The Seven Deaths of Maria Callas © Wilfried Hösl

For an impresario or stage director, working with a visual artist involves far greater expense, and a bold vision can demand a hefty production budget. Aviel Cahn, the director general of the Grand Théâtre de Genève, says it is also necessary “to build a team around them, like with Terry Gilliam”. Gilliam has created two large-scale opera productions for ENO, and a glance at the credits reveals a brigade of assistants who are there to help bring the artist’s vision to life onstage, and to help liaise between the artist and the staff of the opera house. Kramer confirms that in all his collaborations with artists there has been a fleet of associates who he deals with to resolve the technical problems that require experience of the practical constraints of theatre. Accordingly, these projects tend to be multi-party co-productions to share costs and are presented by only a handful of the biggest international opera companies, mostly within the highly subsidised continental European opera landscape.

“It’s a very big and huge risk to give the artist an entire opera.”Marina Abramovic

To justify this this enormous investment, Cahn says, “the work has to be theatrically interesting, and the artist must be sufficiently interested in the opera”. And what an artist can bring is “to question things in opera that people who are working in it don’t normally question”. Or, as Kramer puts it: “the visual artist has no sense of the tradition or the rules of opera.”

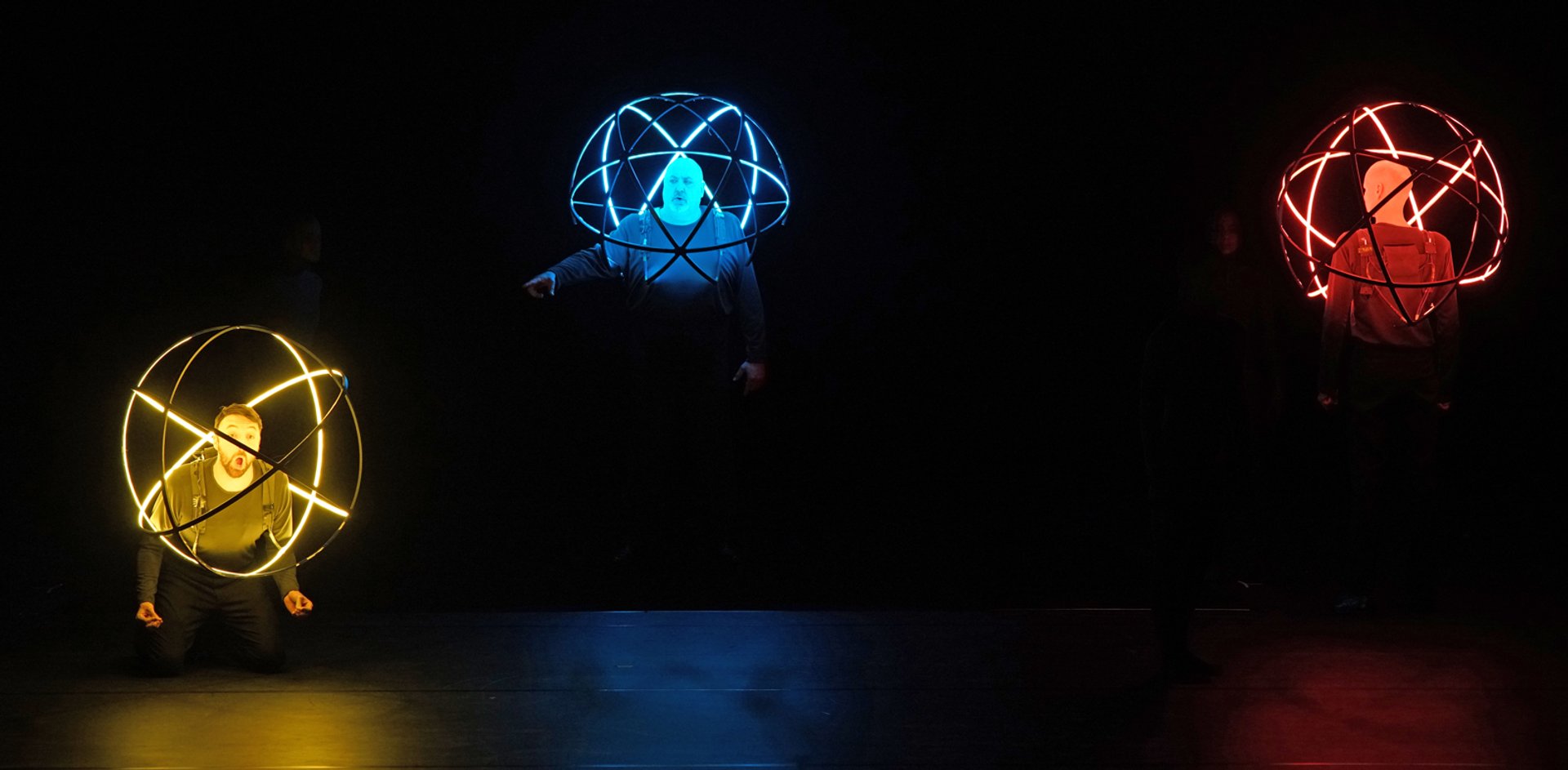

Terry Gilliam collaboration with the English National Opera for Benvenuto Cellini in 2014 © Richard Hubert Smith

Benjamin Britten’s sacred choral work War Requiem, staged by Kramer for ENO, was Wolfgang Tillmans’s operatic debut. The two were introduced by Norman Rosenthal who suddenly had the idea, walking around Tillmans’s Tate Modern retrospective in 2017, that, although the artist had never even seen an opera before, “the way his work engages with war and politics and his sense of colour and composition” meant that he could inject theatricality into what was never conceived as a theatrical work. Kramer described the collaboration as “discovering the work together” through the music. On their research trip to Coventry (Britten wrote the work to inaugurate the new Coventry Cathedral in 1962), Kramer said they suddenly “clicked”, and when they got back to work in the studio, Tillmans began producing images that could be shown on three enormous LED screens, the only scenery onstage. The production has subsequently been seen in Taiwan, and Tillmans enjoyed the process so much that, according to Kramer, he insisted on joining the revival rehearsals in Kaohsiung.

Wolfgang Tillmans’s operatic debut was at the English National Opera for Benjamin Britten’s War Requiem in 2018/19 © Richard Hubert Smith

Cahn warns that often “visual artists don’t think theatrically in the first instance” and, as such, a close support network is crucial to help guide the artist’s voice towards theatrical expression. He has therefore focussed on artists new to opera who he felt had a theatrical drive waiting to be unleashed: he commissioned Marina Abramovic to design the sets for Debussy’s Pelleas and Melisande, and this produced “a remarkable result…absolutely true to her and her work”, borne from what Cahn describes as “Marina’s theatrical versatility” and her ability to produce “a living stage, not just an installation”. Likewise, the Algerian artist Adel Abdessemed, who was due to have directed and designed Messiaen’s epic St Francois of Assisi in Geneva this season, was new to opera, but not to performance and installation. In short, Abdessemed already had experience of working as part of a team, and the requisite theatrical curiosity to give Cahn the confidence, and excitement, that he could create this work as the leading artistic voice from an entirely blank canvas.

Here are two distinct models: pairing an artist as the set and/or costume designer with an established stage director in the hopes of a successful match, and giving an artist the keys to the entire opera house. The former places less responsibility (and therefore less risk) on the shoulders of an artist who may be new to working in a theatrical context, because it is the director who is the ultimate link in the hierarchical chain, and the person with whom the opera management will primarily liaise. This model is well-worn and often leads to repeat collaborations; directors such as Kramer can become ‘known’ for working with visual artists. He is often invited to direct productions with the brief—like with his now cancelled Turandot in Geneva (designed by the Japanese collective teamLab)—of a big ‘artist project’.

The second model is rarer but is becoming more common, perhaps because Modern artists are developing greater ambition and confidence to create and take responsibility for the entire production, not just the design: what Richard Wagner described as Gesamtkunstwerk. In this way, Cahn empowered Abdessemed as director and designer. Likewise, buoyed by her positive experience on Pelleas, a swathe of international co-producers commissioned Abramovic as director and designer for The Seven Deaths of Maria Callas. Abramovic is acutely aware of the higher stakes involved when she is the director. In an interview with the director of the Bavarian State Opera Klaus Bachler she said “it’s a very different thing if you ask an artist to work with the director...on the design and the costumes. But it's a very big and huge risk to give the artist an entire opera.”

War Requiem at the ENO © Richard Hubert Smith

An important ingredient in a successful theatrical collaboration would seem to be the ability of the artist to transfer their voice onto the stage—whatever their regular medium of work. There are many examples of opera productions by exciting artists that end up conventional. Perhaps this is because the artist struggles to adapt to the stage, or simply fails to take advantage of the possibilities it can offer. When asked why the work of some artists fails to transfer, Rosenthal, without quoting examples, says it happens, “when they have no idea about music. When they don’t love the music.”

In contrast, Rosenthal described his recent experience of seeing Wagner’s Parsifal in Munich, designed by the German heavyweight artist Georg Baselitz. This was not Baselitz’s first opera, although he had previously been more drawn to contemporary music. The performance “was extraordinary and spine-chilling...Parsifal became one of Baselitz’s defeated “Heroes” coming back from the Second World War...the images of death that appeared onstage were extraordinary, including the portrait of him and his wife at the end.” The Financial Times, however, wrote “the result feels rather like being locked inside an exhibition for five hours while listening to Wagner.”

Georg Baselitz designed the set for Richard Wagner's Parsifal in Munich in 2018 © Ruth Walz

Over 30 years, the South African artist William Kentridge has forged a parallel career in opera. The stage offers him an enormous canvas to project his world onto; figures and images are closely related, and powerful projection technology allows his animated drawings to interrelate with the characters onstage. His drawings, which in some cases measure only a few centimetres, can be expanded to fill a proscenium of up to 20 metres in width. The opportunity to see Kentridge’s detailed, intricate works at such a huge scale is thrilling. Quite a contrast from the static production style an audience might expect from someone who comes from a non-theatrical background. The polar opposite is Robert Wilson, whose often monochromatic tableaux, strongly influenced by Japanese theatre, progress very slowly: a singer moving her hand into a shaft of light can take several beautiful minutes. Although Wilson began his career in the avant-garde art world, Wilson is now far more famous for his stage work, and the repertoire he encompasses is vast. In the theatre at least, Wilson really is now, according to Rosenthal, “a major artist”.

William Kentridge’s production of Lulu at the English National Opera in 2016 © Catherine Ashmore

Some artists make the transition in the other direction. Both Ralph Koltai, who revolutionised the British stage with a never-before-seen European abstract theatrical aesthetic, and his student John Napier, who found fame and riches through his West End musical theatre collaborations with Trevor Nunn (including Andrew Lloyd Webber’s Cats), developed their practice into fine art. Koltai had always pursued a love of metal collage sculpture, and this work is frequently exhibited alongside his abstract theatre model boxes. When I visited him at his studio to work on our production of Rossini’s The Barber of Seville (Welsh National Opera, 2016), it was clear that these two strands of work were closely interrelated (an object from our model box, later discarded, would, in the subsequent meeting, be found welded to a rusted iron plate Ralph had picked up at a salvage yard).

Star soprano Nina Stemme in Parsifal in 2018 © Ruth Walz

And what of the experience for the performer? The star soprano Nina Stemme who has performed in Der König Kandaules by Zemlinsky, designed by the late Alfred Hrdlicka, the 2017 revival of Hockney’s San Francisco Turandot, and in the Baselitz Parsifal, says: “we participate in a piece of stage art”. Although the aesthetic language of Baselitz and Hockney could not be more different, the result is similar—stunning stage images, in which the performers play a mostly figurative role: one part of the whole imagined world of the artist’s picture. At the end of Turandot, for example, Hockney’s interpretation was that the Princess and her suitor Calaf “are truly in love: the final image was us holding hands and our cloaks carefully arranged to form a heart with the Emperor elevated above the couple.”

The final image of Hockney’s Turandot forms a heart ©Cory Weaver/San Francisco Opera

This dramaturgical, rather than simply decorative, approach to opera production was developed in Olafur Eliasson’s designs for Rameau’s Hippolyte and Aricie at the Staatsoper Berlin in 2018. Eliasson has enjoyed successful collaborations in contemporary dance, but, he says in the programme booklet; “operas are stiff, old, non-negotiable, solidified monsters from the past”. Hippolyte was not Eliasson’s first opera; he had designed the premiere of Hans Werner Henze’s Phaedra at the same address some years before and it was clearly not an entirely satisfying experience for him. The conductor Simon Rattle reported Eliasson saying: “I am never going to work in an opera house again”. But the connection with dance (in his youth Eliasson was a professional hip-hop dancer) presented a point of connection with the director who Rattle proposed. Aletta Collins, who is also a renowned choreographer, describes the working process as being one where Eliasson and his studio would create visual ‘tests’ for ideas in the staging (some of these tests can be watched on the Olafur Eliasson Studio Vimeo channel).

There was no ‘traditional’ scenery, such as the series of Hogarthian two-dimensional etched cloths and flats that Hockney designed for The Rake’s Progress. Therefore, there was no 1:25 scale model box—the traditional means of conceiving and presenting a theatrical design, and—as Collins remarks—‘not a single prop’, even when a critical plot moment in this particular opera relies on a sword. Instead, Eliasson, who designed the set, costumes and lighting, provided a kind of installation that only produced its final result when the dancers and singers “interacted with the elements of light, smoke, mirrors, water to create the picture”, Collins says. As the director, she was responsible for marshalling that interaction: bringing together the elements of design, movement and music into a coherent whole.

Perhaps Eliasson’s approach—and his positive experiences of working in dance—reflects a comforting familiarity for the visual artist in working outside strict narrative constraints. Aviel Cahn alluded to this when he described the choice of repertoire he would offer an artist like Abdessemed or Abramovic: “St Francois, like Pelleas, is a mythic, mysterious piece that suits a visual artist. It’s very philosophical.” Similarly, Daniel Kramer says “Anish [Kapoor] was the perfect artist for Wagner’s Tristan and Isolde because his body of work is about the mythic, the mystical and interior meditation”.

Olafur Eliasson’s designs for Rameau’s Hippolyte and Aricie at the Staatsoper Berlin in 2018 © Karl and Monika Forster

The historical contribution of visual art to opera production is significant, and the modern story begins when Wieland Wagner relaunched the post-war Bayreuth Festival in 1951. His grandfather, the composer Richard Wagner, controlled both the visual and the musical presentation of his large-scale operas. They were closely associated with a revolutionary hyper-naturalistic presentation which, for the first time, plunged the audience into darkness and hid the orchestra away under the stage to make the action seem more real. Wagner’s operas celebrated chivalry, knights and European mythology, and they were later co-opted by Hitler as a paean to his third Reich and Aryan superiority. As his first project as festival manager, Wieland Wagner—who had originally trained as an artist and had been profoundly influenced by Adolphe Appia—created an abstract and philosophical production of Parsifal which was totally unlike any performance the audience had ever seen before. Opera had shed its kitsch and started to interest visual artists. Around the same time, the British film director Peter Brook was collaborating with Salvador Dali on an avant-garde production of Salome by Richard Strauss, and Ralph Koltai had returned from his role as an interpreter at the Nuremberg Trials to begin his career as a stage designer.

Richard Wagner's Lohengrin performed in August 2018 at the Bayreuth Festival Bayreuth, Germany, with designs by Neo Rauch and Rosa Loy © Bayreuther Festspiele / Enrico Nawrath

Bayreuth remains a crucible of artistic ambition and controversy and famous artists continue to be invited to create work on the famous ‘Green Hill’. In 2018 the American director Yuval Sharon (the first Jewish director invited to Bayreuth) staged Lohengrin in designs by the husband and wife team Neo Rauch (set) and Rosa Loy (costumes). That painterly production should have been revived this year, but Covid-19 provoked the first cancellation of the festival since it was reopened by Wieland Wagner. The production was not entirely well-received at its premiere, although the Bayreuth audience is famous for boo-ing productions which are subsequently acclaimed as genius, such as the Patrice Chereau Ring Cycle in 1976.

“Brook was robbed at gunpoint, and he begged the bandits to let him keep Dali’s drawings and to take his silk pyjamas instead. They agreed.”

Two artists who never got to find out if their work would be well-received by Wagner’s audience are Lars von Trier and Jonathan Meese. Von Trier who, like Chereau, was entirely inexperienced in stage production, was due to direct The Ring in 2006 but he pulled out after his concept (the entire stage is in almost continual pitch black apart from tiny pin-pricks of light, not always coinciding with the location of the singers) was considered impossible, impractical or undesirable. Likewise, the German artist Jonathan Meese, who had been hired to direct Parsifal in 2016, was fired, allegedly due to budgetary concerns. Meese was an experienced stage performer; in 2013 he was prosecuted for giving the Nazi salute shortly before he painted a swastika onto a large alien doll which he then fellated. Meese suspected that this incident frightened the composer’s great-grand-daughter, Katharina Wagner, the current director of the festival. And well it might, the association of Wagner with Hitler would surely have been too much temptation for Meese to resist, despite his assurances that no Nazi imagery would appear onstage. Meese had in 2005 created a performance called Jonathan Meese ist Mutter Parzifal at the Staatsoper Berlin in which he gave a minute-long Nazi salute accompanied by the music of Parsifal. One might question why, then, he was engaged to direct this opera at Bayreuth in the first place. Meese, in an interview in Der Spiegel suggested, “art has no place in Bayreuth. Meese didn’t fail with Wagner, Bayreuth failed with Meese.”

Covid-19 has laid many plans to waste—or, at least, delayed productions. The revival of David Hockney’s The Rake’s Progress, Abdessemed’s St Francois of Assisi, and Kramer’s Turandot collaboration with teamLab are all on hold. This opera, with its Western orientalist view of Chinese myth, presents significant challenges of cultural appropriation to opera companies today. It was this title, however, that drew the curiosity of Ai Weiwei for what would have been his first opera production as director and designer at the Rome Opera in October, now cancelled. One can only wonder what this political artist would have made of the kitschly offensive romanticised story of a Chinese princess whose suitors are murdered when they fail to answer a riddle, featuring orientalised fictional ‘Chinese’ music by the Italian composer Giaocomo Puccini. We can only hope that it will—like Calaf, Turandot’s successful suitor, who belts out Nessun Dorma in the final act—evade the executioner’s sword and live to tell its tale.

Famous art x opera collaborations—and lesser known ones

David Hockney has created several opera productions for Glyndebourne and San Francisco from 1975-1993, many directed by John Cox. His collection of set models is held in Salt’s Mill, Yorkshire. His first work, The Rake’s Progress by Stravinsky was due to be revived by Glyndebourne this summer.

William Kentridge’s production of Lulu at the English National Opera in 2016 © Catherine Ashmore

William Kentridge has created several globe-trotting productions as director and designer since 1999, supported by a large team. His work has taken him across nearly 300 years of operatic repertoire from one of the first operas ever written, The Return of Ulysses by Monteverdi, via Mozart’s The Magic Flute to two of the most brilliant works from the twentieth century by Alban Berg – Lulu and Wozzeck.

Derek Jarman designed sets and costumes for English National Opera’s first production at the London Coliseum, Don Giovanni, directed by John Gielgud (1968). A geometric, abstract set design featuring largely period costumes was not well-received—The Times criticised his ‘drop-curtains, with their emphasis on sexual symbols and general harshness’, asking ‘on what plane can these possibly engage with Mozart’s music?’ The 26-year-old Jarman would never work in opera again, although in 1989 he directed a film adaptation of Britten’s War Requiem, featuring Laurence Olivier’s last acting role.

Anish Kapoor designed the set for Tristan and Isolde at the ENO in 2016 © Catherine Ashmore

Anish Kapoor designed several opera productions around the world. His most recent project was the sculptural Tristan and Isolde for ENO, directed by Daniel Kramer in 2016. The set featured a gold pyramid in the first act, keeping the lovers physically apart, and a rockface in the final act, when they were thrust together but unable to touch.

Georg Baselitz designed the set for Richard Wagner's Parsifal in Munich in 2018 © Ruth Walz

Georg Baselitz, although particularly fascinated by contemporary music, created a hugely influential Parsifal with director Pierre Audi in Munich. Other productions have included Punch and Judy by Harrison Birtwistle in Amsterdam (1993) and Ligeti’s Le Grand Macabre in Chemnitz (2013).

Jörg Immendorff, a student of Joseph Beuys and creator of the Café Deutschland series (featuring Norman Rosenthal in a cameo appearance), designed the sets for Richard Strauss’s Elektra, Shostakovich’s surreal opera The Nose, and Stravinsky’s The Rake’s Progress which presented the central character, Tom Rakewell, as a kind of self-portrait. He later developed this work into a series of paintings in homage to Hogarth.

Mariko Mori worked on Madame Butterfly at La Fenice in Venice, in association with the 2013 Venice Art Biennale. Another orientalising work by Puccini, Mori presented a hugely acclaimed and unusually abstract production of what is a conventional narrative opera, drawing on her personal heritage and featuring an enormous central sculpture which reflected the infinite cycle of life and death.

Salvador Dali collaborated with Peter Brook on Salome at the Royal Opera House Covent Garden in 1949. The production, which Brook described to his biographer Michael Kustow as a "hallucinatory fantasy", nearly didn’t happen. On his way back from a visit to Dali's studio to work on the designs, Brook experienced "a dangerous encounter that might have figured in a Dali nightmare." Brook was robbed at gunpoint, and he begged the bandits to let him keep Dali’s drawings and to take his silk pyjamas instead. They agreed. This production was loathed by its critics (one wrote "it is difficult to speak in the restrained language appropriate to a Sunday paper") and it brought Brook’s career as director of productions at Covent Garden to an abrupt end, but subsequent generations bemoan the missed opportunity to see it. Both Norman Rosenthal and Daniel Kramer rate it as the one production of an artist-designed opera they most wished they had seen.

• Sam Brown is an independent opera director. His productions include The Barber of Seville at the Welsh National Opera and the Grand Theatre de Genève designed by Ralph Koltai, and La Clemenza di Tito at the Theater an der Wien, Vienna.