In Empire of Pain: The Secret History of the Sackler Dynasty, Patrick Radden Keefe charts the fortunes of the Sackler family, which prided itself on a long and distinguished history of philanthropy in the US and UK. Institutions such as the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Smithsonian in Washington, DC, and the Victoria and Albert Museum and Serpentine Galleries in London, have all benefitted from the family’s largesse.

But in the past three years, evidence of unethical behaviour by some of the family members when marketing OxyContin, an opioid produced by the family firm Purdue Pharma, has led to a spectacular fall from grace (more than 450,000 Americans are thought to have died of opioid-related overdoses over the past two decades). On 15 March, Purdue Pharma filed for bankruptcy in a New York court in an attempt to settle nearly 3,000 lawsuits against it from state and local governments, Native American tribes, hospitals and other organisations.

Patrick Radden Keefe, the author of Empire of Pain © Philip Montgomery

“Arthur [Sackler] had become accustomed to a certain level of solicitous flattery from museum directors”Patrick Radden Keefe in Empire of Pain

Keefe, a senior writer at The New Yorker, describes the publication as an “investigative chronicle of three generations of the Sackler family and the mark that they left on the world”. According to the jacket blurb of the US version, Keefe’s analysis reveals “the scorched-earth legal tactics that the family has used to evade accountability” amid the “indifference to human suffering that built one of the world’s great fortunes”. Below are three key takeaways from Keefe's account of a tarnished dynasty.

The Met missed out on Arthur Sackler’s Asian art collection because it did not woo as well as the Smithsonian

Keefe outlines the complicated and difficult relationship between Arthur Sackler—one of the brothers who built the empire but died in 1987 before Purdue Pharma developed OxyContin—and Philippe de Montebello, the former director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. The Met’s Sackler Wing, which houses the Temple of Dendur and opened in 1978, was funded by Arthur and his siblings, Raymond and Mortimer Sackler

Arthur Sackler, a psychiatrist, owned one of the largest collections of Asian art in the world, and had for years kept a “private enclave at the museum”—a separate private gallery that Sackler used as his personal storage facility for the collection.

Keefe writes: “For more than a decade, Arthur had been subjecting the Met to the dangle, giving every impression that he would eventually bestow his priceless art collection to the museum. But to his dismay, he found that he did not get along with the latest director [De Montebello], a cultured curator with an aristocratic mien. Arthur had become accustomed to a certain level of solicitous flattery from museum directors, but he did not feel that he got it from de Montebello.”

S. Dillon Ripley, the then head of the Smithsonian in Washington DC, comes wooing Arthur Sackler in the meantime. “And so the dance began, Ripley reeled in Arthur slowly,” writes Keefe. Eventually, “the two men forged a deal in which Arthur would agree to donate a thousand objects from his collection, which Ripley estimated to have a value of roughly $75m… When the deal was announced De Montebello tried to mask his annoyance. ‘Disappointed? The disinherited always have that view,’ he said to The Washington Post.” In 2019, the Smithsonian Institution rebranded the Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery as the National Museum of Asian Art. (Similarly, the Serpentine Galleries in London quietly dropped the Sackler name from its branding earlier this year.)

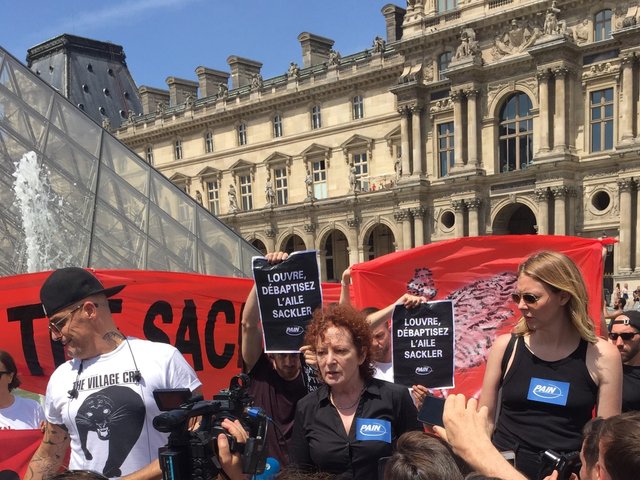

Nan Goldin lying on the floor outside the Musée du Louvre © Stéphane Renault

Small print discovered by Nan Goldin’s Pain group saved Louvre’s blushes

The publication throws light on the artist Nan Goldin’s successful campaign to remove the Sackler name from the galleries of the Musée du Louvre in Paris. Goldin’s activist group Pain (Prescription Addiction Intervention Now) protested at the museum mid-2019, claiming the Louvre was not contractually bound to display the Sackler name in perpetuity.

The Sackler attributions were nonetheless gradually removed from the museum's website and signs at the entrance to the formerly named rooms were removed or covered with tape. “Some members of her group Pain had also discovered that there was a special circumstance at the Louvre that might allow them to make a breakthrough. Consulting the museum’s bylaws, they learned that the Louvre reserved the right to sunset any naming agreements after 20 years. And the Sackler Wing had carried the name for more than two decades,” writes Keefe.

“Within two weeks of Goldin’s protest, the president of the Louvre [Martinez] announced that the wing would ‘no longer carry the Sackler name’. The museum claimed that this decision had nothing to do with Purdue Pharma or OxyContin or Nan Goldin’s protest, and was instead just a routine housecleaning. The rooms weren’t being ‘de-baptised’, a spokeswoman insisted—just updated,” he adds. According to Jean Luc-Martinez, the Louvre director, there was indeed a 20-year limit on naming rights (the Sackler donation was made to the museum in 1997; Martinez did not say why the name had not been removed two years earlier).

Did the Sacklers hire private investigators to tail Nan Goldin?

Pain activists allege in the book that they were followed by investigators who may have been hired by the Sacklers. Keefe explains that one of Nan Goldin’s deputies in the organisation, Megan Kapler, was leaving Goldin’s Brooklyn apartment when she noticed a man sitting in a car, watching her. The same man was spotted on another occasion monitoring Kapler.

“The members of Pain assumed that the Sacklers must have arranged for them to be followed, but also that the man was probably a subcontractor of some sort,” writes Keefe. The same man also appeared in front of Goldin’s house. “He stood leaning on his car, a smirk on his face, and began to clip his fingernails. Had he been sent to monitor them or intimidate them? In a way, it didn’t matter. His presence was an affirmation. Their campaign was working. In May [2019], the Metropolitan Museum of Art, home to the original Sackler Wing, announced that it would ‘step away’ from gifts that it determined were ‘not in the public interest’,” writes Keefe. Members of the Sackler family could not be reached for comment.

Empire of Pain: The Secret History of the Sackler Dynasty by Patrick Radden Keefe

• Empire of Pain: The Secret History of the Sackler Dynasty, Patrick Radden Keefe, Picador, 560pp, £20 (hb)