Walking into a room of Jackson Pollock’s drip-paintings in 1951, Helen Frankenthaler said the experience was like moving to Lisbon with no Portuguese and feeling compelled to put down roots: “I wanted to live in this land, and I had to live there but I just didn’t know the language.” This wild terrain was Abstract Expressionism and, while it may have seemed a far-flung monoglot culture to the precocious 22-year-old Frankenthaler, her own syntax of forms would soon come to express so much of what that language was able to articulate.

Frankenthaler’s immersion did not take long. After completing her art school studies at Bennington College in 1950, she moved back to New York, and by the following spring she was offered her first solo show at Tibor de Nagy Gallery on the strength of her formative abstractions.

Helen Frankenthaler's Mountains and Sea (1952) © 2020 Helen Frankenthaler Foundation, Inc./ARS; Photo courtesy of National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC

But something was missing. On 26 October 1952, in the back of her West 23rd Street studio, Frankenthaler followed Pollock’s method of dispensing with an easel in favour of the floor, which allowed her whole body to move on top of and around the canvas. She sketched a few charcoal lines suggesting central forms, and then laid on turpentine-thinned pink, blue and salmon, modulating carefully between managed spontaneity and intuitive constraint. Frankenthaler called the painting Mountains and Sea, partly in reference to how the abstract topographies of paint reminded her of watercolours she had made that summer in Nova Scotia.

“She holds this levity in place, catching it not as the butterfly collector nets the specimen, the better to see it desiccate back in the collection, but miraculously to let the caught thing respire at the tip of her fingers,” writes Alexander Nemerov, whose lyrical biography Fierce Poise: Helen Frankenthaler and 1950s New York comes out this month. Diagonal handwriting arches towards the bottom-right corner of the unprimed canvas and marks the date: 10/26/52. Nemerov adopts this diurnal timekeeping for Fierce Poise, which he describes as an energetic “young person’s book” following Frankenthaler as she lives out her 20s, reinventing herself at “every turn”.

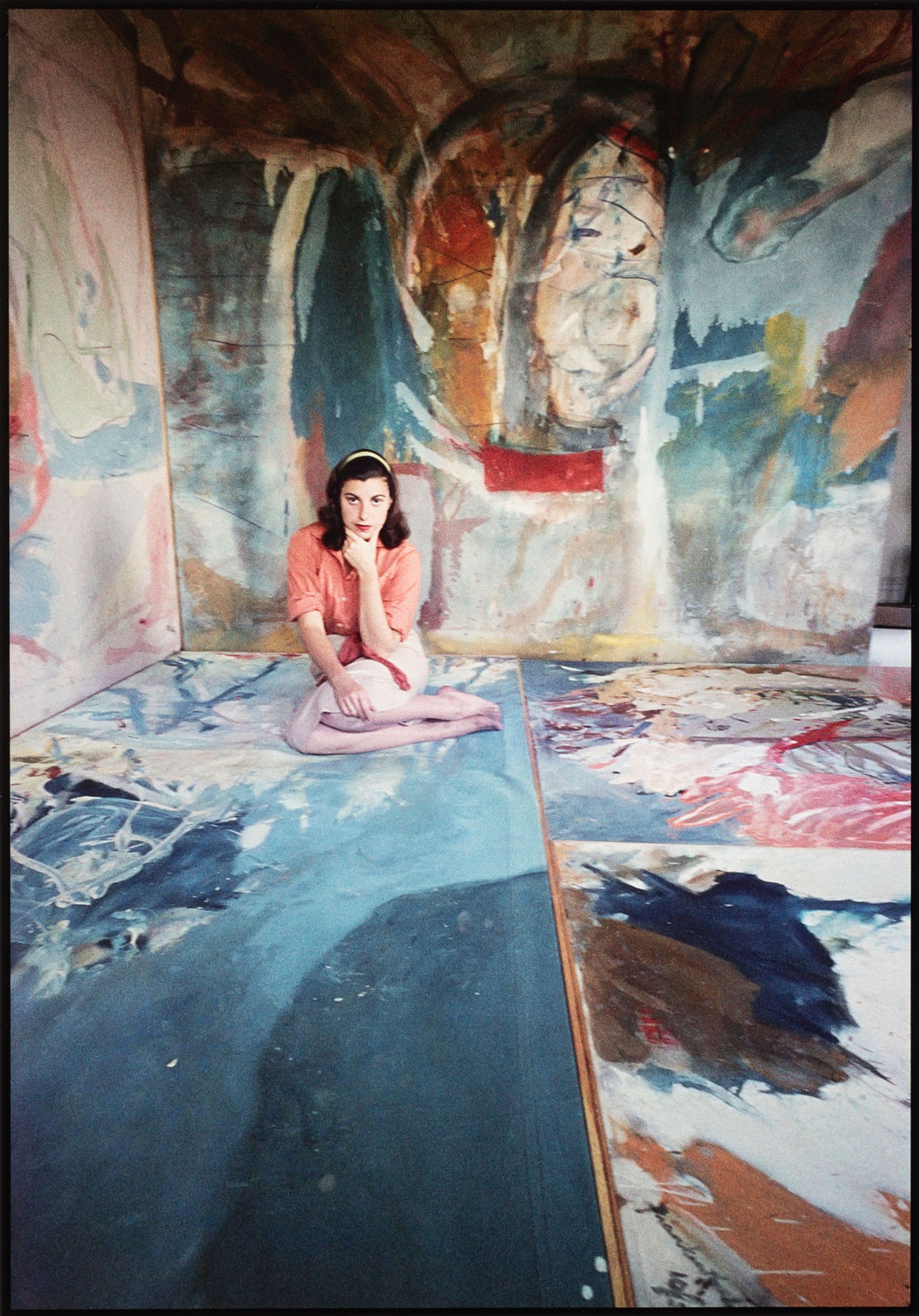

Helen Frankenthaler photographed for Life magazine by Gordon Parks in May 1957 The Jewish Museum, NY, Purchase: Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation Fund, 2018-75 Artwork © The Gordon Parks Foundation

“Helen’s colours and stains were her material and method”Alexander Nemerov, author

Nemerov claims to have known Frankenthaler’s work before he could even speak, through her Bennington College friendship with his father, the poet Howard Nemerov. Like most of his generation, Nemerov the younger was a child of post-modernism who had grown tired of the embarrassing earnestness of the Abstract Expressionists. They were too vulgar, too apolitical. Call it growing up or the benefit of hindsight, but Fierce Poise is a masterful return to what once moved Nemerov in his youth, before the tenure-track intellectualism took hold. It is a defence of acquiring “enough perspective (in [his] own sweet time) to see that the world is made of hatefulness that deserves to be called out but also a kind of lightness and peace that are themselves ethical forces”.

Eleven chapters span as many years. Each one is anchored to a day of extraordinary change and possibility, from Frankenthaler’s arrival into the art world dressed as Picasso’s Girl before a Mirror at a fancy-dress party at the Astor Hotel in May 1950, through to her first and celebrated solo retrospective at New York’s Jewish Museum a neat decade later. The book's cover image depicts such a day, in this case 13 May 1957, when the US photographer Gordon Parks photographed Frankenthaler in her studio for a feature in Life magazine. (Parks's image will be included in the exhibition Modern Look: Photography and the American Magazine opening in April at the Jewish Museum in New York).

Frankenthaler's Before the Caves (1958) © 2020 Helen Frankenthaler Foundation, Inc./ARS

Fierce Poise is the latest of a particular kind of artist biography that is unabashedly personal, revelling in the hushed intimacy of a memoir in a way that seeks to demystify great artists by recreating their formative years in straightforward terms—often through what those breakthroughs say about the writer’s own life. “Helen’s colours and stains were her material and method,” Nemerov writes. “Mine in portraying her is the one she invented.”

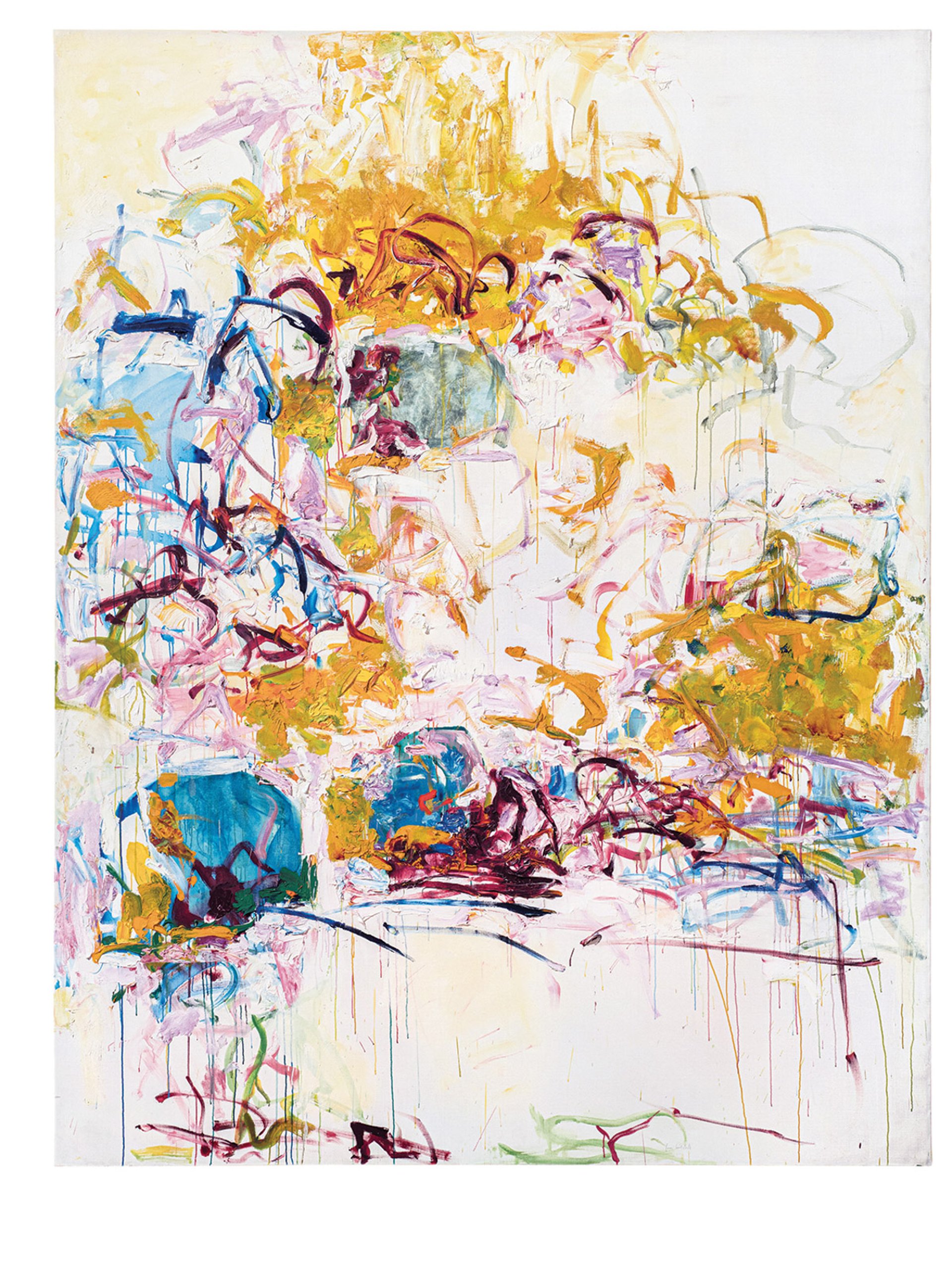

Joan Mitchell’s Sans Pierre (1969) Collection of The Long View Legacy LLC; © Estate of Joan Mitchell

Fierce Poise arrives in the midst of significant new interest in Abstract Expressionism, particularly in the women and artists of colour who have been marginalised from these histories for too long. Mary Gabriel’s book Ninth Street Women (2018) or exhibitions such as Lee Krasner: Living Colour, which concluded its four-stop European tour in January, and the forthcoming Helen Frankenthaler: Radical Beauty at the Dulwich Picture Gallery in London, demonstrate how we are only now beginning to understand the full story of these—above-all other identifiers—great abstract painters.

Joan Mitchell, published in January by Yale University Press in advance of a delayed Baltimore Museum of Art exhibition—which will now take place in 2022 after the show opens at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art in September—does justice to an artist who, like Frankenthaler, arrived in New York with grand ambitions and a formidable control of paint.

Mitchell’s City Landscape (1955) © Estate of Joan Mitchell

Take, for instance, City Landscape (1955), a frenzied tangle of fierce pinks, blues and yellows in the centre, while above and below pearlescent forms of off-white animate the abstracted horizon-line. It looks like distant flickers of neon on a grey winter’s day, or a teeming island seen from above; it is both a landscape and the world of painting at a time of irrepressible painterly invention. “I love this big horny red painting (City Landscape),” writes the poet Eileen Myles, who contributed eight poems to the book, “because it’s bitch work. It’s tooth and claw.”

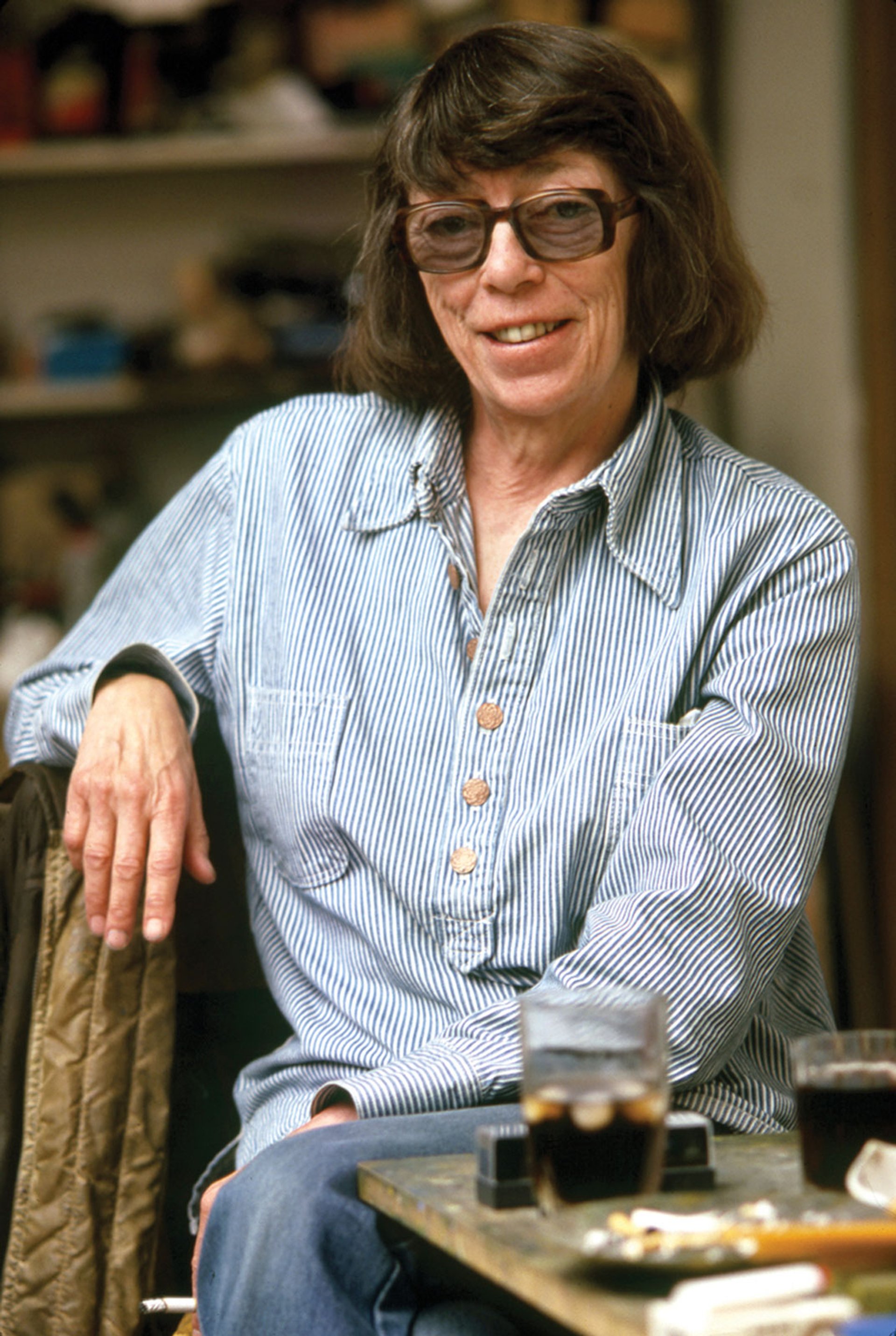

Joan Mitchell in her Vétheuil studio in 1983 © Joan Mitchell Foundation; Photo: Robert Freson

Both Frankenthaler and Mitchell came from families of considerable means, but that counted for little in the spit-and-sawdust New York art scene of the 1950s. Tooth and claw were essential materials for both artists, crafting their art on their own terms, even before they knew exactly what that might be.

• Fierce Poise: Helen Frankenthaler and 1950s New York, Alexander Nemerov, Penguin Press, 288pp, $28 (hb)

• Joan Mitchell, Sarah Roberts and Katy Siegel, Yale University Press with the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, 384pp, $65 (hb)