Amit Sood, the Bombay-born director of Google’s Cultural Institute and Art Project, is showing me a computer programme that would have made the Surrealists cry with joy. It is X Degrees of Separation, by the artists Mario Klingemann and Simon Doury, which uses computer vision algorithms to make random connections between any two works of art, like a game of Exquisite Corpse to the power of a hundred. It is a product of their Experiments section, where they bring artists who are currently at the cutting edge of technology and connect them to their database of images and their partner museums so that they can collaborate.

This is the left field of Google Arts & Culture, the not-for-profit segment of Google founded in 2011 as part of the Google Cultural Institute to digitise the works of art in museums. It purposely avoids defining culture—in 2016 it added natural history to its spread—but it does not do popular culture “because plenty of others do that”, Sood says. They now partner with 1,500 museums and cultural institutions in 70 countries.

The Google Art Camera takes images in such high resolution that you can see the brushstrokes of a painting or the tiniest intricacy of an embroidery; it gives the closest one can get to the “hands-on” experience of a work of art without actually touching it. Museums can also upload their own images, and six million photos, videos, manuscripts and other documents of art, culture and history—including hundreds of thousands of hi-res images of works of art—are now on the platform. These are presented institution by institution, exhibition by exhibition (6,000 of them), or in “stories”, worked on by Google and its partnering institutions.

The stories are becoming increasingly elaborate, some of them mini-documentaries, with video, music, presenters and texts. Among the thousands of topics they have tackled are the Guggenheim Bilbao (this includes a film in which a free runner leaps from girder to girder and turns air somersaults in the Richard Serra sculptures), an explanation of contemporary art and women who changed India’s history. Its latest, We Wear Culture, unites the collections of 185 museums to tell the story of fashion.

Google Arts & Culture is more than a mere recorder of art collections and is now a major producer of cultural content with a huge reach through social media, the app (which has had over one million installs) and with 50 million people using the Arts & Culture website. Behind them are the 500 million monthly art-related searches on Google itself, and its team is working on making that experience better for them, too.

It all started because Google employees are expected to use 20% of their time thinking about new projects that will benefit the company. Sood, then working as a software engineer, put an idea to Nicholas Serota, then director of the Tate, Thomas Campbell, then director of the Metropolitan Museum, and Glenn Lowry, the director of New York’s Museum of Modern Art (MoMA). He said he loved their museums after discovering that they were not just for posh people, but why didn’t they all open up a bit? He’d like to look at MoMA’s Starry Night (1889) by Van Gogh at home while drinking a glass of wine, but not with a low-quality thumbnail on Google Images. “I want a magnificent version, and I want your curator telling me the story. I want an experience, and when I have time to come to New York, I’ll go and see the original,” Sood said.

Then he discovered other teams in Google doing archive scanning—for example, with Yad Vashem Museum in Israel—and he realised that there were a lot of people who were passionate about culture and about finding a way for digital to embrace it, “so we proposed it to the senior management, and it fitted very well with the mission”.

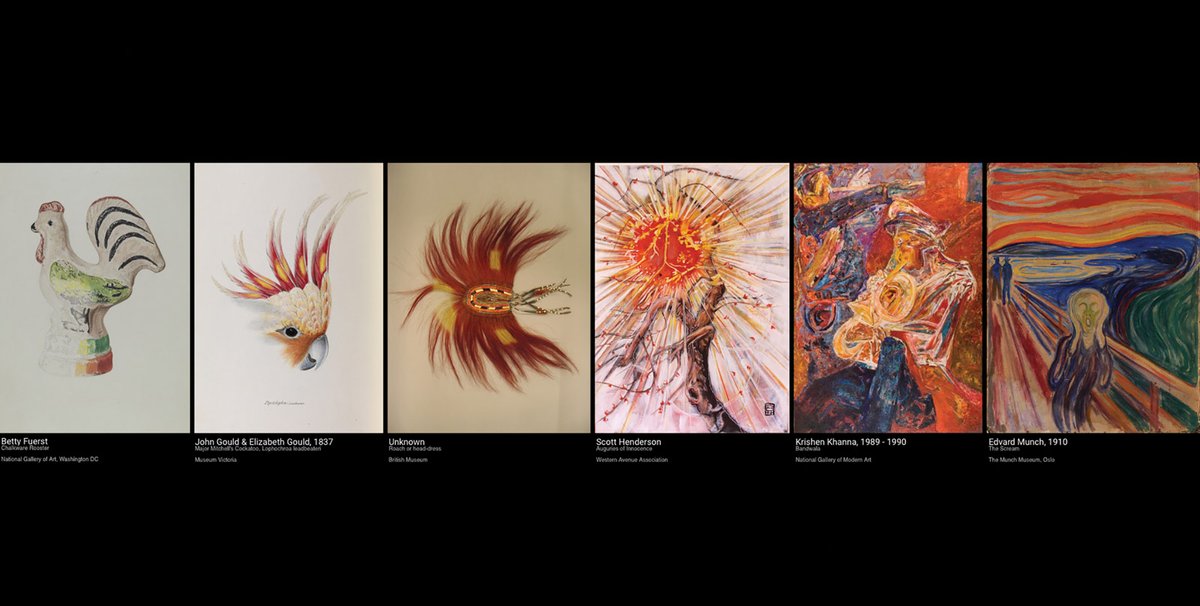

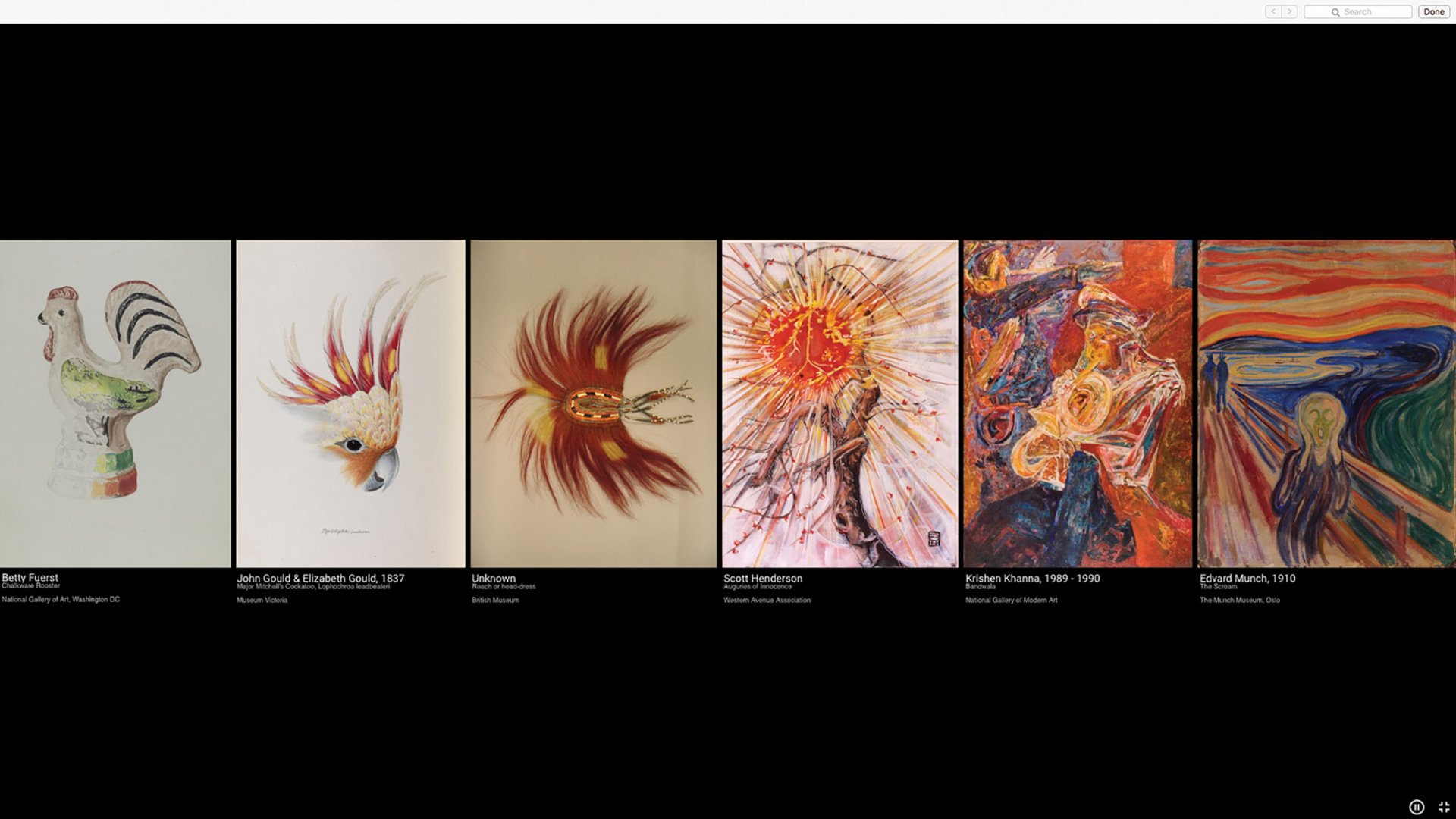

1910 From the collection of; 1940 From the collection of; Betty Fuerst; Chalkware Rooster; National Gallery of Art; Oslo; The Munch Museum; The Scream; Washington DC; to Edvard Munch X Degrees of Separation The hidden paths through culture By Mario Klingemann & Simon Doury

The Art Newspaper: What is the Google mission?

Amit Sood: The mission is to make information accessible and organise it efficiently, and the way I pitched it at that time to Eric Schmidt [then CEO of Google] was to say, “Do you believe the world of culture is organised?” And he said, “No, I don’t.” I said, “Do you think it’s accessible, then?” And he said, “Well, no, not really.” So he was one of the people who thought, this needs to be a proper mission; we need to carve it out as a non-profit team, with its own independence, its own charter, so to speak. I didn’t dream it all up; it came step by step.

When we started the project back in 2011 with the museums, people said, “This is going to replace the physical experience.” But we’ve found over the last few years that the more digital has embraced culture, and culture has embraced digital, the greater the increase in physical footfall across cultural institutions. Nobody has been able to calculate a direct correlation because it’s very difficult to track, but they are seeing that the digital has a positive impact, that people get interested to go—otherwise, the 4th of July fireworks in America would just be a big video.

Key question: who gets to keep the copyright in the images and stories?

The partnering institutions have all the rights and full control over their images and content they publish on the platform, and this applies also to images that they take with equipment provided by Google, like the Art Camera, and to the stories made with Google.

How are the museums using your very hi-res digital images?

It depends on the size of the museum. The bigger ones use them in their educational programmes and to spearhead some of their internal conversations and feed into other programmes of their own. However, they can also connect them back to a larger story that they can commission with us. A lot of them are using this initiative to develop their own digital progression, so for some big museums who are already quite capable of doing a lot of their own stuff, we are more like a test pad. The Metropolitan Museum recently announced their open data policy but told us, “If it hadn’t been for you guys coming in and digitising and helping us structure this online, we might not have done it.”

Now you’ve gone far beyond just digitising; you’ve become producers, in a sense.

Our core still remains the images, but we can have an interesting idea that comes out of them. Our biggest project at the moment is about fashion. It’s called We Wear Culture, and it started when we realised that a lot of museums were uploading fashion objects onto the platform but it was just sitting there. And then we met Natalie Massenet [the founder of the design fashion portal, Net-a-Porter], Anna Wintour [the editor of American Vogue] and a few other important people in fashion, and they said, “Wow, this is amazing, but why is it not narrated?” And we said, “Okay, let’s create this project called We Wear Culture.”

I thought it was just going to be the Met, the V&A and a few others, but 185 museums have come together—the Parsons School of Design, Central St Martins, Kyoto Costume Institute, Museo Salvatore Ferragamo etcetera—and that’s when we realised that it’s all very siloed: schools are doing their own thing; private foundations do their own thing. Museums collaborate for shows, obviously, but that takes time, while here it’s much easier to facilitate this collaboration—well, still tough by Google standards, but easier by museum standards.

And the project now is all about the icons, the movements, the making, the art—and investigating how to get YouTube young people to embrace culture. For example, there’s this woman who’s very popular on YouTube, who tries to explain things like the hoodie, which young people don't know actually has connections to historic artefacts.

Our Grand Tour series, on the other hand, is the product of the desire to record an intangible story, such as a festival: for example, the fireworks for the feast of the Redentore in Venice, or the horse race in Siena. We’ve done Florence, Venice, Siena and Palermo and now we’re expanding. We fund them. We are providing the resources to tell these stories because if it’s done under the aegis of the Google Cultural Institute, it has to be non-commercial.

These are complex, sophisticated projects, so have you got editors, curators or scriptwriters?

No, what we have is a content group. Base content comes from the partners [the museums]; it creates the corpus. Then each partner gets access to a curating and storytelling tool. The curators become the editors, so 95% of all the stories you see here will have been told by the museums themselves. In some cases, we will also provide help. For example, here are ten animals with superpowers but they all belong to different museums, so we found a person to write the story, and we have one or two people who work with freelance writers.

We’ll provide the resources—sometimes technological, sometimes financial—and we’ll tell them what works if they want to attract an online readership. Four years ago, when we rolled out the storytelling format, we’d get very long academic papers submitted to us and then the partner museum would complain, “No one’s reading them.” And we’d say, “Well, if you want people to read them, you’re going to have to start with the image; you’re going to have to bring interesting facts that people can understand easily because you’re catering to a different audience.” Only in that sense are we giving them the ideas.