Artists working in “new” media have never been so widely admired—a generation of artists in their 20s and 30s, including Amalia Ulman, Neil Beloufa, Ian Cheng, Jon Rafman and Cécile B. Evans, are now shown internationally. Exhibitions have also moved beyond specialist kunsthallen such as ZKM in Karlsruhe, V2 in Rotterdam and YCam in Yamaguchi, Japan. Digital art was the subject of a major show, Electronic Superhighway, at the Whitechapel Gallery in London this spring, and the focus of this summer’s Berlin Biennale. Meanwhile, the New Museum in New York, which has digital art specialists Rhizome in residence, is working with the Hong Kong-based K11 Art Foundation on an exhibition on art and technology, due to show in China next year.

Yet a quarter of a century after the emergence of digital art, it continues to raise challenges for museums, galleries and collectors. As the Serpentine Galleries in London reveal their third digital commission, James Bridle’s Cloud Index, we look at some of the reasons why digital art is still not fully in the mainstream.

The artist: Rafael Lozano-Hemmer Rafael Lozano-Hemmer emerged in the 1990s from the performing arts: a piece in the Whitechapel’s Electronic Superhighway show—a giant eye that follows visitors around the room (Surface Tension, 1992)—began within a set design for a dance work. “At the end, we would invite the audience to participate; they realised that the eye’s movement wasn’t a projection timed to the dancers. Suddenly they weren’t passive spectators, they couldn’t escape the tracking device. That was a pivotal moment for me,” he says.

Despite the fact that he is preparing for survey shows in Brazil, Korea and Canada, he says “there remains a big disconnect between media art and established museums”. At first, museums thought it was “simply playful” or that they were buying into Silicon Valley hype, like “the idea that technology is going to emancipate us all”. Now, he says, “museums realise that technology is inevitable—if our economy, war, politics and relationships are mediated through globalised networks of computer control, it’s natural to use media to express poetry or criticism”.

But if Lozano-Hemmer feels that artists have less need to justify their choice of media, he believes that they must professionalise their practice. Collectors worry about the future of their acquisitions: how does a work that can be copied multiple times have a value? How do they deal with works built with software that, through rapid updating, effectively disappears? What about hardware: is a particular monitor integral, or just a piece of kit that can be replaced with whatever is current when it fails? How much does an idea matter, how much its physical realisation?

Lozano-Hemmer has become a powerful advocate for addressing these issues before a work is sold. “When you acquire one of my works you get a bill of materials and it says this work is made out of this screen, this motor, this software and so on, and it tells you if this is replaceable, and if yes, what are the constraints.” The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York and Tate in London are among the museums that have used the source code of his works to update them to current platforms, demonstrating that his studio need not be involved in the update. “So the artist has to try to pre-emptively think what is acceptable and unacceptable for a work, effectively, to be re-performed,” he says. He also regularly attends conservation conferences, has drafted best-practice guidelines for fellow artists, and is developing new business models for studios to encourage them to offer conservation support for their own work.

The museum director: Benjamin Weil The Tate in London, MoMA and the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA) have been at the leading edge of disentangling the intellectual and practical challenges posed by digital art—thanks in part to the support of the New Art Trust, founded in 1997 by the Californian media art collectors Pamela and Richard Kramlich. Their advice platform, Matters in Media Art, was updated in September to provide the latest information for collectors, artists and institutions in caring for works with moving image, electronic or digital elements.

Benjamin Weil, the artistic director at the Botín Centre in Santander, Spain, argues that the issues surrounding new media art are not fundamentally different from the problems of conceptual art. His “epiphany” was a sculpture by Tinguely, which was displayed motionless, with a video next to it. “Tinguely’s project was to have sculpture in movement, but here you didn’t have the weird noises, you didn’t have the eerie feeling seeing this monstrous object moving in space. The preservation of the work had become more important than the artistic intent.”

Museums have been left with problems like this because they acquired works in the past without establishing with artists how to deal with decay and obsolescence—combined with institution’s ingrained resistance “to accepting sometimes you have to let a work die”. The crucial issue now, Weil says, is that contemporary artists do not compound the situation. “Artists using technology can’t say, ‘It’s not our responsibility to take care of the work, it’s yours.’ We in museums have to say, ‘We can’t look after the work without you, we want to be sure that whatever decision we are going to make will not betray you.’ ”

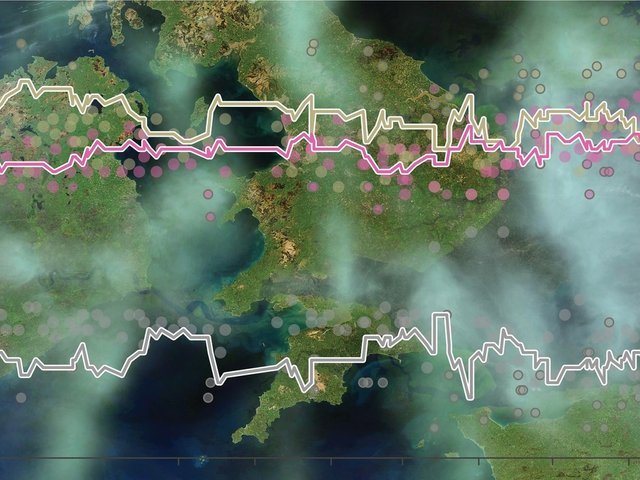

The digital commissioner: Ben Vickers Ben Vickers is the curator of digital at the Serpentine in London. The gallery has just launched its latest commission, a complex work on the nature of the cloud and voting patterns by the journalist, writer and artist James Bridle.

Vickers says that digital commissions present particular challenges. In March this year, the gallery launched Bad Corgi, a strange computer game/mindfulness app by the New York-based artist Ian Cheng. While Vickers describes Cheng as “a genius” he also says that the year he spent working with the artist was “one of the most difficult things I’ve done”. One of the issues, he says, is the time spent working on software, “because it’s in the production of the software that the ideas emerge”, adding that Cheng made, then rejected, a number of prototypes. With programmers commanding high day rates, “the whole thing is expensive”—indeed, Vickers himself helped with some of the coding.

Curators with “a comprehensive understanding” of technology are rare, which can add extra risk to projects. “This gallery has years of experience of making exhibitions. But when you are working with an artist and they need someone who knows about epigenetics and can also write code, that’s not something that most art museums know how to deal with. Digital curators have to build their own networks with the tech world and universities to find the help they need.”

The commercial gallery: Steven Sacks Artists working in new media are generally represented by specialist galleries such as bitforms gallery in New York and Carroll Fletcher in London, or by smaller, emerging galleries.

Steven Sacks is the founder of bitforms gallery, one of the earliest to specialise in new media. He will celebrate the gallery’s 15th birthday with an exhibition in San Francisco in November: unusually, he represents several generations of artists, from the 78-year-old Manfred Mohr to artists born in the 1980s such as Sara Ludy. He describes his start as “challenging” but says he “saw the potential of what was possible and how art would evolve with each generation of technology”.

Sacks says that although prices for work by top digital artists are still low compared with the equivalent painters (“which are exponentially more expensive”), it can also represent an opportunity. “Computational, screen-based, interactive media is the most exciting development in the past five to ten years,” he says. “It is still a challenge because the market for this work is smaller than for traditional work: but it is the next big leap forward in the way artists can present their ideas.”

He also says the emergence of high quality yet more affordable 4K screens is proving attractive to collectors. “In many cities, even at the very top end, apartments are not vast: in the past very thin screens were really expensive, but now a 75in, 4K screen is accessible, and—as long as the artist hasn’t specified otherwise—you could rotate single channel video works and generative pieces on the same screen.” He is also involved in the creation of a platform (Niio) to help collectors store, manage, conserve and loan video, followed by computational work. “More and more people can code, so we may get to the point where it’s easier to find people who can maintain digital pieces than look after master paintings,” he says.

The art advisers: Lisa Schiff and Sebastien Montabonel Lisa Schiff is a New York- and Los Angeles-based art adviser with a strong interest in digital art. She is sanguine about looking after the work, as long as artists provide good documentation. “It’s not like scraping a painting, which—although you have to repair it—is forever tarnished. If there is a glitch with a digital work, working on the mechanics doesn’t affect the value.”

She says that there is a strong primary market for Cory Arcangel, Ian Cheng and others including Seth Price, Rachel Rose, Josh Kline, John Gerrard and Tabor Robak, but she only has two collectors building collections of this kind of work in depth. The issue, she says, is that “there isn’t really a secondary market. An Arcangel work based on an old Mario Bros [game] came up and it didn’t do well. It’s a seminal work and I wish I had bought it.” But, she says, “it took 150 years for there to be a market for photography: it might be hard for us to get our heads around it now, but it won’t always be this way.”

London-based art consultant Sebastien Montabonel, who recently organised a conference on media art and museums, Media in the Expanded Field, argues that the perceived challenges of digital work also present advantages. “The number of collectors who want to buy something that doesn’t necessarily fit easily into a home, that will probably break down in the way a painting doesn’t break down, that very quickly looks dated in a way that a painting doesn’t ever look dated, that are willing to take all these risks, will always be small,” he says. But for those that do, the outlay “can have a massive impact,” he says. “For far less money, you will meet all the artists, people will invite you to talk on panels, you’ll be offered places on museum boards.” With risk, he suggests, comes impact.

The collectors: Anita Zabludowicz and Patrizia Sandretto Re Rebaudengo Sespite the challenges, a cadre of dedicated collectors has emerged: the Kramlichs in San Francisco; Julia Stoschek in Düsseldorf and Berlin; Patrizia Sandretto Re Rebaudengo in Turin; and the Borusan Collection in Istanbul.

The British collector Anita Zabludowicz (who calls Stoschek her “digital sister”) has mounted a number of digital shows, including this year’s Emotional Supply Chains at the Zabludowicz Collection in London. She began collecting the work of Pipilotti Rist in the 1990s and more recently she has focused on artists including Jon Rafman, Cécile B. Evans, Ed Atkins and Rachel Maclean. Museums have not, she believes, given enough attention to digital “because not all curators have recognised the full potential of the virtual world as an art form”. She is a supporter of Daata Editions, which commissions digital works and then sells them in larger editions than the art gallery norm, meaning prices start at as little as $100. “We hope to change the mentality of the art lover,” she says, “encouraging people to use their smart electronic devices to seek out digital art in the same way they would seek out new music or TV.”

Patrizia Sandretto Re Rebaudengo remembers collecting video by artists including Doug Aitken and Steve McQueen in the 1990s; this month, she is showing works by Ed Atkins, shortly to be followed by Josh Kline. She recalls people questioning the artistic importance of photography and video, and argues that some of the same issues affect media art today. “Now it is hard to imagine museums not showing photography and video like they show painting and sculpture,” she says. “For a new generation, digital art will be equally important in understanding what art is. It is the medium that best represents the ideas of this century, and it is the most direct way for newer visitors to understand art: it is much closer to their own experiences.”