The celebrated Paris-based art review Cahiers d’Art has reissued a monograph dedicated to the US artist Arthur Jafa, which includes conversations with fellow artists Mark Leckey, Frida Orupabo and Rashaad Newsome touching upon topics such as race, career choices and the legacy of the Italian Renaissance sculptor Bernini. The book also contains several examples of Jafa's work as well as reproductions of notebooks that he has been filling with assemblages of found imagery since the 1990s.

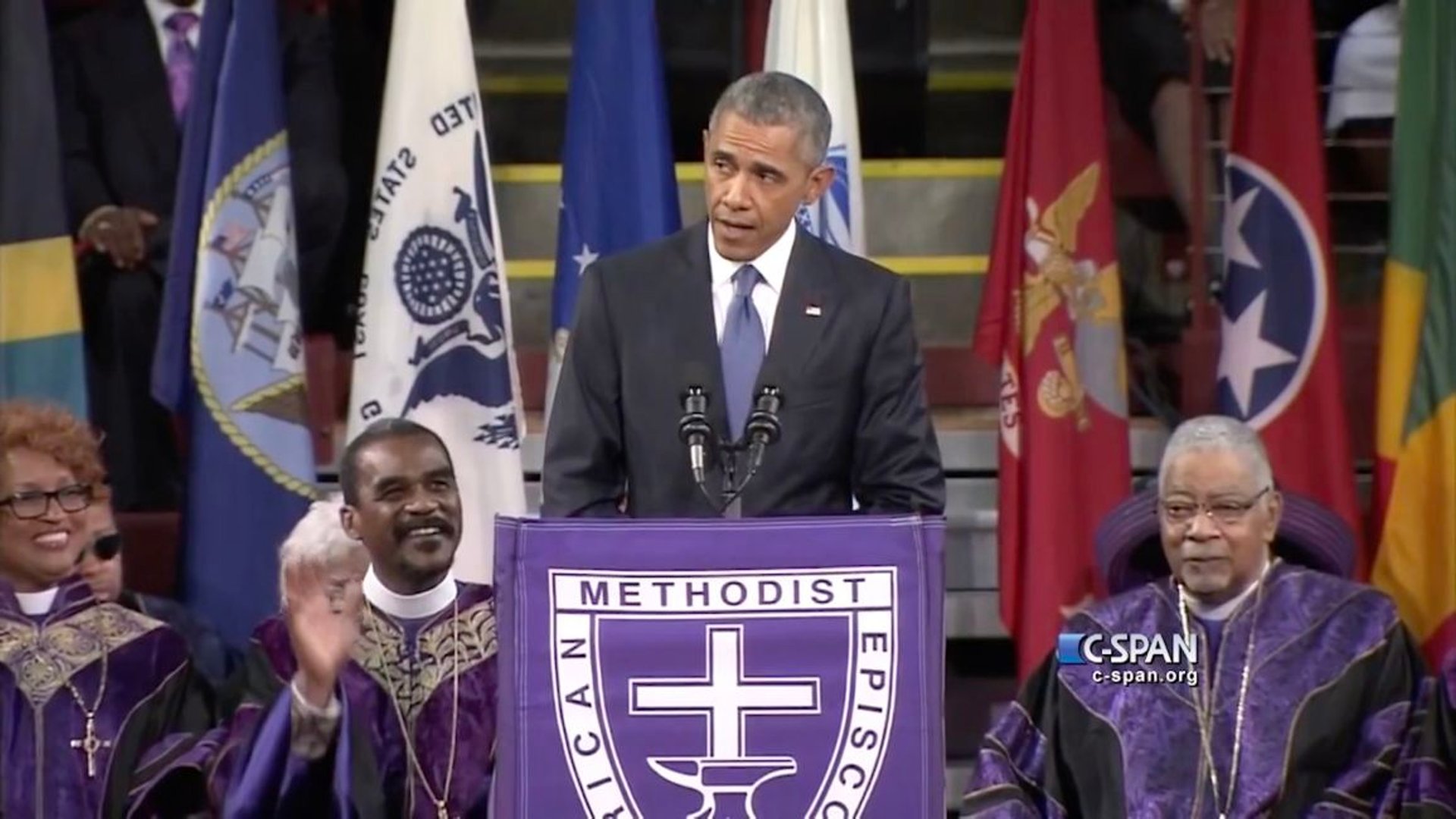

Jafa's largest exhibition to date opens next week at the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art in Humlebaek, Denmark (9 December-9 May 2021) and will include several new works as well as his masterpiece, Love is the Message, the Message is Death (2016). The searing seven-minute film chronicles Black America, bringing together clips from multiple sources, including TV news, police footage and pop videos, set to Kanye West’s hip-hop track Ultralight Beam. It shows violence against African Americans as well as the triumphs of Black culture and features excerpts such as Martin Luther King waving from the back of a car, Beyoncé in the music video 7/11, and the former US President Barack Obama singing Amazing Grace at the eulogy for the nine Charleston parishioners killed by a white supremacist.

In a conversation with Mark Leckey, Jafa describes the “state” he was in when he made Love Is the Message, the Message is Death and how the work came about.

Arthur Jafa Photo: Robert Hammacher

I used to have this recurring daydream, I’m strolling on a boardwalk, it’s sunny, I’m in my head, trying to figure out what I want to do. I glance to my right and see one of the ships that’s docked, I see windows and there are Black people chained in the hold, under the decks. What do you do in that moment?

I’m the kind of person who keeps stepping. Not because I don’t care, but keep stepping because on a certain level, I realize that I could go and burn that boat down, which might kill everybody on it, first of all, but I’ve always been the kind of person whose anger, whose rage is somewhat suppressed, clamped down. If anything, I’m like, “Where are the docks that are making these ships? That’s what I want to burn down.”

I’m slightly dispassionate about the iteration of the problematic that’s in front of me. I’m a little clinical about it, because I dwell in the place of “this shit needs to be rooted out”. You’ve got to go to the root of the problem, you can’t be trimming branches, that’s not going to do anything. It may save X amount of people there, but it’s not, fundamentally, going to change anything.

So, my state, in the face of what seemed like a tsunami of footage of Black people getting killed... Which is strange because Black people are always getting killed, and it’s something Black people have always known in America.

A still from Jafa's Love Is The Message, The Message Is Death (2016) showing President Obama singing Amazing Grace at the funeral for South Carolina state senator Clementa Pinckney

All during the eighties, with Eleanor Bumpurs and this kind of stuff, people were like, “Police are using excessive force against us. They’re using chokeholds, they’re killing people.”

And other people would say, “You guys are too close to it, too emotional, you’re this and that”. Rodney King was only the beginning. Those witnesses just happened to have video cameras, not cell phones, but that’s the beginning of citizen-documented video, verification that the things we’re describing are not figments of our imagination, these things are real. And they’re not exaggerations.

Like, if you had to describe the Rodney King thing: “a swarm of cops surround this guy striking, kicking, shocking him repeatedly with clubs, boots, tasers for twenty plus minutes.” It seems hyperbolic, right? But the footage was there for everybody to see. It was the same thing with Abu Ghraib. I was teaching in the MFA program at Bard. Abu Ghraib happens, and one of my co-faculty does this incredible presentation on the images, their iconography and symbolism, the Spanish Inquisition, the excruciation, the dunce caps, the KKK, the whole thing.

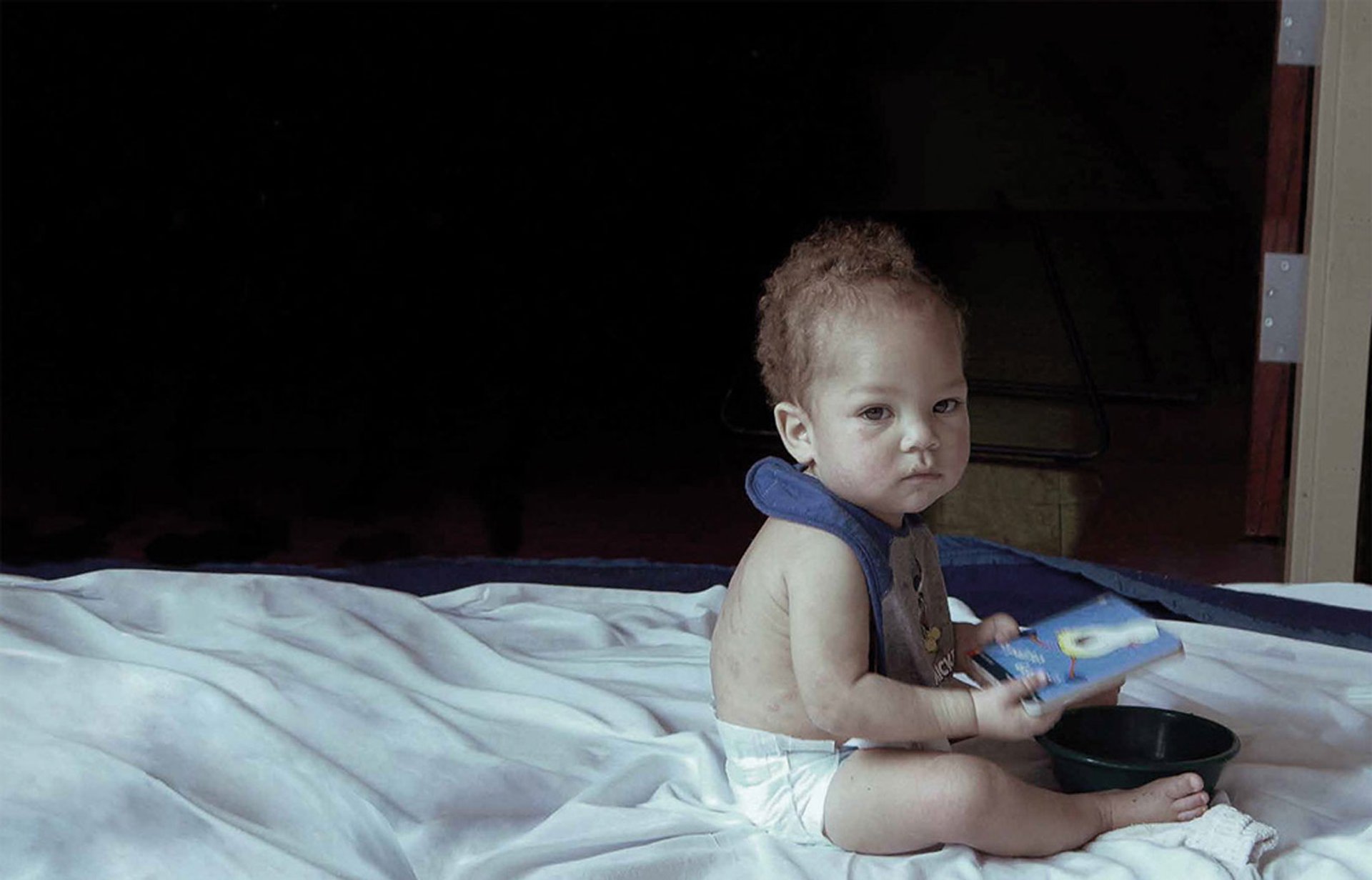

Arthur Jafa's My Little Buddha (2018), which features in a new Arthur Jafa monograph Courtesy Arthur Jafa / Cahiers d'Art

During the Q&A he says that one of the things that so troubled Americans seeing these images was that they couldn’t account for where they’d come from, they couldn’t imagine them. I was one of maybe three or four Black people in an auditorium filled with over 200 students and faculty and everybody starts looking towards me, and I got a little irritated. Like, “Don’t be fucking looking at me! I’m not going to be the conscience of this body, you guys need to have some opinions about this stuff yourselves.”

At a certain point I did stand up and say, “I don’t want to speak for all Black people, but I can say with a lot of confidence: nothing about these images surprises any Black person.” You know what I mean? We didn’t need a picture or video to know this kind of shit was and is going on, our whole history has been this way. And if it hasn’t happened to you directly, it’s like seven degrees of separation, gestalt trauma.

There’s not a single person I know who doesn’t know someone intimately it’s happened to, or some version of it. Even if it’s just what’s termed “micro aggression,” it’s a tsunami of micro aggression, you know what I mean? So, I was like, “This is kind of absurd.”

So, when YouTube comes online (along with Facebook, WorldStarHipHop), a certain threshold is crossed in terms of folks having video in their phones and given the frequency and intensity of this extrajudicial, state-sanctioned violence towards Black folks, of course, it was a perfect storm.

A still from Jafa's Love Is The Message, The Message Is Death (2016), which will be on show at the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art Courtesy the artist and Gladstone Gallery

And it seemed like every other week there was new footage of somebody being murdered.

A few years before that I’m working on a documentary and this anti-police-violence group out of New Orleans showed us this dashcam footage of police killing a Black man.

I remember looking and thinking, “God, this is incredible”. You saw the police car chase this guy down, he’s literally running from the camera, as they’re shooting out of the car at him. Then they get out and continue shooting him in the back, like twenty times or more. It was crazy. He’s trying to crawl away and they’re following on foot, almost casually still shooting him in the back. It’s still the most shocking thing I’ve ever seen. Somebody had leaked it, hoping that it would get out.

That getting out was still contingent on someone broadcasting it. YouTube circumnavigated all that. And at a certain moment, every week or two, there was something else, and everybody was freaking out. I wasn’t, because the more spiritually or emotionally appalled I am by something, the cooler I get on the surface. So, I was being super, super cool.

Then the footage of the sister arrested while in the car with her kids, in which nobody actually got shot, nobody got killed or beaten even, there was just something about that, that just broke me, man. When I saw that, I remember crying; I cried when I saw that footage. Because it just reminded me of my mom, I guess.

• Arthur Jafa: 43rd Year, Cahiers d'Art, 166pp, €90 (pb)

• Arthur Jafa, Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, Humlebaek, 9 December-9 May 2021