In the first week of January 1937, six months into the Spanish Civil War, Josep Renau, Republican Spain’s dynamic young director of Bellas Artes, approached Picasso to commission a large work of art for the Spanish Republic Pavilion in the forthcoming Exposition Internationale des Arts in Paris. It would hang pride of place. As the world’s most famous artist, and as the director of the Prado museum in absentia on a salary of 15,000 pesetas per annum, Picasso was pressured to produce a powerful propaganda piece to highlight the horrors of the Spanish Civil War.

The art historian Miguel Cabañas Bravo relates how Renau found Picasso relaxing in a Parisian bar with friends. Sensing he was overdressed, Renau took off his jacket and threw his tie in the bin, before entering to try and persuade the artist to help. If Picasso was initially reluctant, a few days later the organising committee, including the pavilion’s architect Josep Lluís Sert, finally persuaded him to accept the commission. By the end of June, Picasso delivered on his promise with his masterpiece Guernica. That Picasso delivered the commission on time is almost miraculous. That he produced the most powerful and iconic image of the 20th century is off the scale.

For the first three-and-a-half months after receiving the commission Picasso did nothing, as if frozen in the headlights. It was only after a site visit to the Spanish pavilion that he was finally forced to react. On 19 April, in a quickfire drawing, he essayed out the complexities of the problem he faced. Picasso’s work was to be displayed in a transitional space, on the side wall of the entrance portico, neither inside nor out, adjacent to the restaurant and opposite the theatre. It would be the first and last image the visitor would see and take away from a pavilion that was planned as a dynamic, noisy installation mixing theatre, photo-collage, craft, poetry, propaganda and dance.

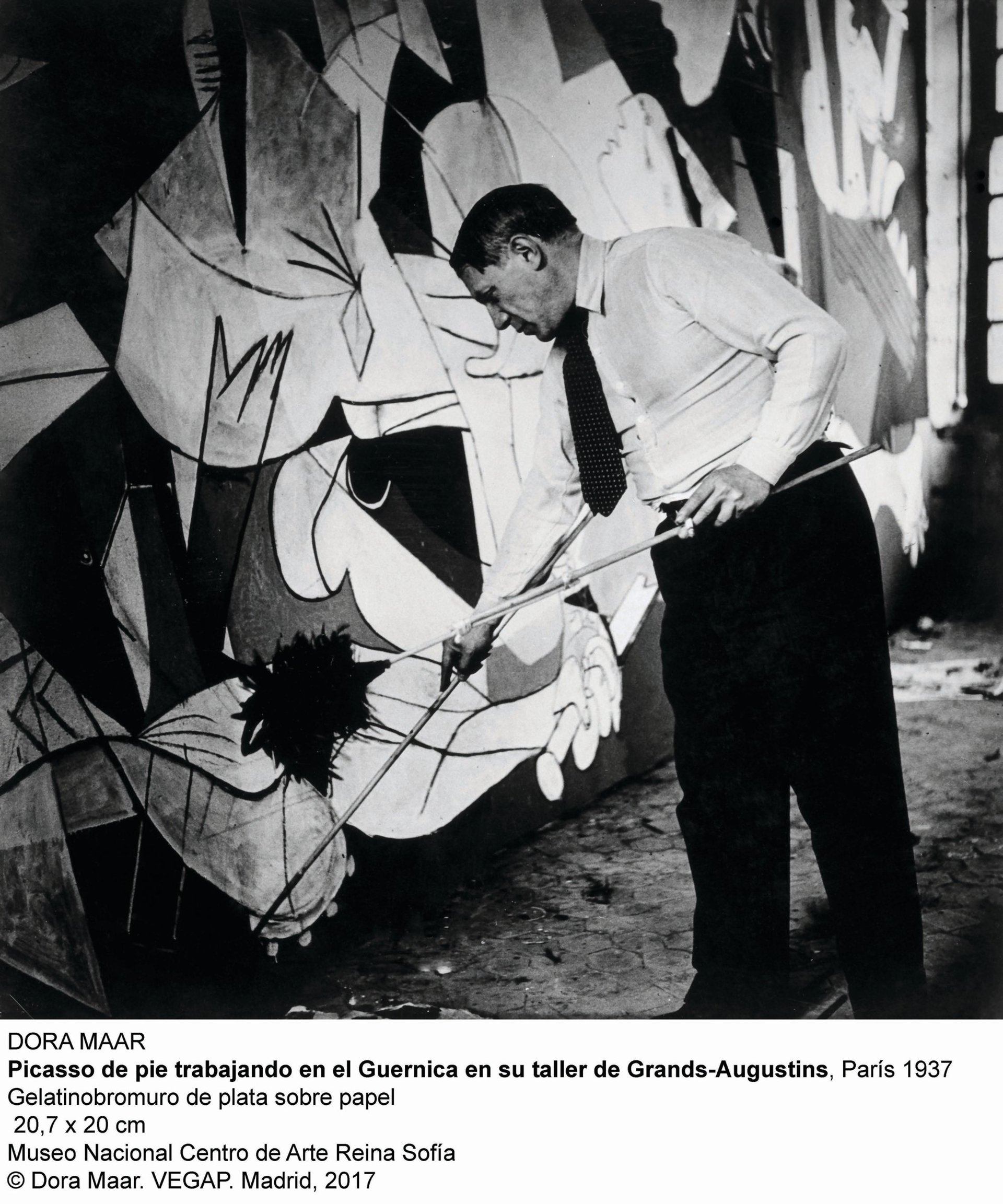

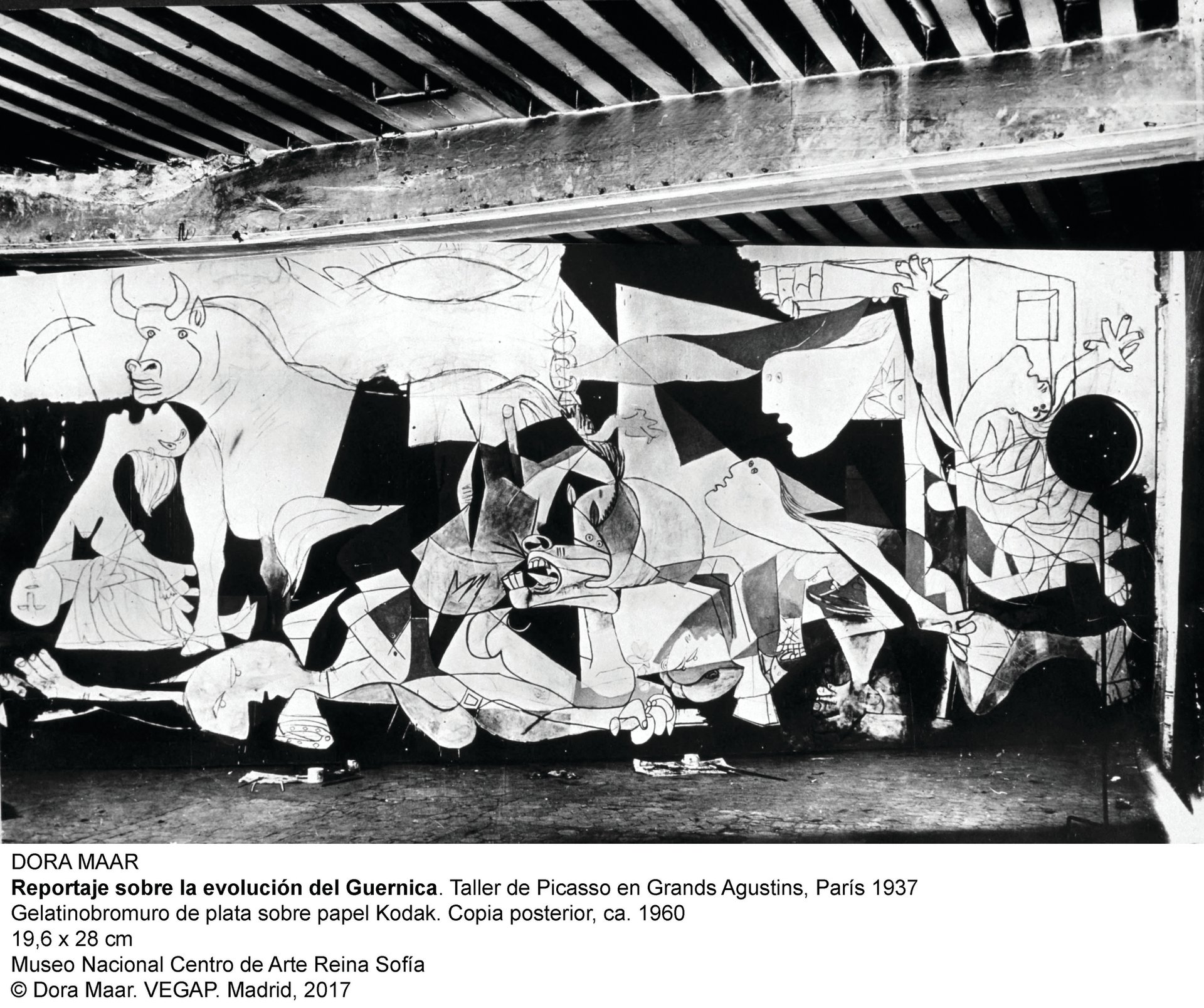

Dismissed almost always by critics as a failed attempt, Picasso’s drawing deals head on with the spatial tension that would appear in the final painting. He was, however, no nearer to finding a subject. There was almost 27 sq. m of emptiness to be filled. In the new studio on the Rue des Grands Augustins, previously frequented by his mistress Dora Maar but more significantly used by the Labalette brothers working on the Spanish Pavilion—who used it to store their construction equipment—the canvas awaited him. Upstairs, in the old grain store, there was just enough space to squeeze it in at an awkward angle. Despite the Spanish genius for last-minute improvisation, an assistant had taken the time to prepare the blank canvas carefully.

José María Cabrera and Maria del Carmen Garrido made a microscopic technical analysis of Guernica when in 1981 it was transported from New York to Madrid. They established that Guernica’s canvas was comprised of rough jute primed in a deliberately antiquated way in order to create a luminosity like a stained glass window bouncing out reflected light. By working layers of lead white primer, one layer mixed with graphite, Picasso had created the reflective qualities of dark mirror backing, which, when covered with a thin film of lead white and finely ground glass, was not unlike the cobalt blue smalt employed by Rembrandt. It lent the canvas a special aura as it waited for its subject.

On 26 April the German Condor Legion, over a period of three hours, completely destroyed the Basque city of Gernika with a terrifying display of the new “blitzkrieg” method of saturation bombing. According to Xabier Irujo, the co-director of the Center for Basque Studies at the University of Nevada in the US, the destruction of Gernika was planned as a belated birthday present from Göring to Hitler, orchestrated like a Wagnerian Ring of Fire. Picasso had finally found the subject for his painting.

The genesis, evolution and inspiration for Picasso’s masterpiece is still the subject of hot debate—as, too, is the struggle to interpret the complex, giant canvas. The standard art history of looking for sources has found potential inspiration for Guernica in myriad disciplines, ranging through sculpture, painting, print, photography, film, Greek tragedy, mythology and theatre. To add to this, the historian Martin Minchom has convincingly argued for the importance of contemporary reportage. On 8 January 1937, uncensored reports filed by the Paris-Soir journalist Louis Delaprée describing the atrocities of Franco’s bombings in Madrid were finally published. Delaprée’s tragic death—shot down in a plane en route from Madrid to Paris a few weeks earlier—had become a cause célèbre. His copy was horrific and harrowingly graphic; in one scene, Delaprée described a woman, howling into the skies on Madrid’s Gran Vía in her final death throes with a dead baby suckling on her blasted breast. Once read, it was impossible to forget.

Over the years, since publishing my book Guernica: The Biography of a Twentieth-Century Icon, potential new sources and interpretations have surfaced. Springing immediately to mind are the animal friezes at Darius the Great’s palace at Persepolis, dating from the fifth century BC, in today’s Iran. They were being uncovered throughout the 1930s, contemporaneous to Picasso’s growing fascination with the Minotaur. The lion and boar frieze on the Apadana staircase and the battle between man and beast depicted on the walls of Xerxes’s harem would certainly have attracted the artist’s attention as he obsessively reworked ancient myths and rituals of death.

Perhaps the most strikingly obvious source of inspiration in classical art is the third-century AD sarcophagus depicting the Calydonian boar hunt in the Capitoline Museum in Rome that would have caught Picasso’s attention on his visit to Rome in 1917 with Diaghilev’s Ballet Russes, just as earlier it had transfixed Flaxman and Rubens. In the centre, Meleager and Atalanta stand shoulder to shoulder ready to take on the monstrous boar caught up in a complex jumble of limbs, rearing horses and savage dogs. The resulting visual melange is not unlike Picasso’s earliest attempts to resolve the spatial complexities of Guernica as recorded in Maar’s photographs.

Graphic energy In Rome, Picasso surely marvelled at the incredible mosaics in the Farnese Palace whose equestrian ballets between man and horse were so reminiscent of the bull ballet recortes, Minoan in ancestry, that were part of his childhood and are still practised in Spain today. Painstakingly, thousands of tesserae were laid out in black and white to create a powerful field of graphic energy. As exciting is the likelihood that Picasso studied Mithraic sculptures depicting the tauroctony—sacrifice of the bull—the finest example of which is on display in Cordóba’s Archeological Museum, in Picasso’s native Andalucía.

Never mentioned is a work by one of Picasso’s favourite artists, Henri Rousseau. His dramatic 1894 painting, War, in the Musée d’Orsay, depicts a wild-haired valkyrie riding a crazed pantomime horse over a heap of dead bodies. It is easy to imagine Picasso with his famed Spanish black sense of humour and love of morbo—with its double meaning of both morbidity and sexual arousal—falling in a heap laughing at the hairy harridan astride her horse while secretly admiring Rousseau’s brave abandon to his uniquely primitive style.

I have begun to think that Rubens’s powerful Death of Hippolytus (1611-13) in the Fitzwilliam Museum is almost certainly Picasso’s disguised source for Guernica. It is a perfect conflation of myth, war and sexual tension. There is only one problem with my discovery: the painting hung at Woburn Abbey in the Duke of Bedford’s private collection until 1951. Picasso never saw it, although it is possible he saw Richard Earlom’s late-18th-century print after Rubens, which is appropriately in black and white.

Amid my struggles to “fix” Guernica, the English artist Luke Caulfield approached me with a fascinating and entirely plausible suggestion. In preparation for the bombing of the Prado, most of the great masterpieces had been put into cases in the basement ready for transport by lorry to the relative safety of Valencia. Larger sculptures that were difficult to move were protected under mountains of sandbags. Miraculously, almost nothing was damaged, despite the fact that the Prado took various direct hits.

On 16 November 1936, however, a small 16th-century alabaster Renaissance funerary relief depicting a stylised Roman triumph was seriously damaged when the Prado was deliberately targeted again. Benedetto Cervi Pavese’s relief of 1531-32 was carved in honour of the Duke of Nemours, killed in the 1512 Battle of Ravenna while leading a cavalry charge. There are certainly similarities between Pavese’s work and Guernica, a hunch made even more plausible following Caulfield’s detective work that uncovered an illustration of the damaged relief on the 13 February 1937 front cover of L’Humanité, Picasso’s favourite newspaper, adjacent to a large headline announcing the imminent exhibition in Paris where Guernica would eventually be shown. Although he in no way suggests that Picasso focused exclusively on this one source, Caulfield leaves us with a possible reading that is certainly intriguing.

Picasso’s magpie instinct and voracious visual memory is legendary but there is also a much broader issue at stake. With Guernica, Picasso had taken on the grisaille of mourning and grief, and the peculiarly powerful tenor of Spanish religious ritual. There are anecdotal reasons to believe this is true. On the same day that Henry Moore visited Picasso’s studio to witness him working on Guernica, there was another lesser known visitor who remembers the occasion rather differently. It was a star-studded day with Max Ernst, Paul Éluard, Roland Penrose, André Breton and Alberto Giacometti also present. The poet/mentor figure of José Bergamín, who acted as Picasso’s political sounding board, is rarely mentioned.

Religious theatre Many of the distinguished artists had tried to dissuade Picasso from testing out colour on Guernica and muddying its appearance. Bergamín reminded Picasso that, as the inventor of collage, he could just stick on scraps of wallpaper to check on the effect rather than applying paint, which would be irreversible. Maar’s photo has recorded the moment for posterity. It was one of the few times that Picasso worked on an image with a certain degree of collaboration. At the end of the meeting Picasso handed to Bergamín a cut-out paper lágrima—a human tear—which he ordered him to keep safe in a reliquary, take out every Friday while Guernica was on show and place on the painting wherever he wanted. Was this mere high jinks? A perfect piece of morbo, a cruel jibe at Maar, whom he regularly cast as his weeping woman? Or did Picasso mean something more profound?

Grisaille is central to Spanish art, but it is also central to the rituals of Spanish faith. The theatre of Spanish religion is acted out inside the church and in the plazas and streets. During Corpus Christi the processions march under dark canopies that are dramatically lit up as the sun breaks through only to return seconds later into a much darker penumbra. There are lanterns everywhere, some held out on high. The procession, the noise, the emotional electricity, the drama continues as if nothing has happened.

In 1937 Easter had fallen early, on 28 March, but Corpus Christi was on 1 June, almost exactly when Picasso invited his artist friends to see his work almost complete. Grisaille, it was blatantly apparent, had won the day. Like a funeral pall stretched over the painting there was now, at last, an appearance of finality.

Grisaille is Spain’s colour and tone. It was obvious from day one of the commission that Picasso would play on the full range of clichés, from sol y sombra to death in the afternoon. From his vast visual memory bank Picasso could draw on Goya for examples of dramatic lighting and the use of black and white. Goya’s The Third of May (1808) was obvious. Picasso surely knew the apocalyptic reverse of Bosch’s The Garden of Earthly Delights (1503-15) where the deluge has drowned the world. And, of course, Van der Weyden’s Deposition (around 1435) that imitates the carved retablos or kast—cupboards—where full-scale carved figures are placed in a shallow claustrophobic space. Van der Weyden energised his work by playing on the tension between the flat pictorial possibilities of paint and the 3D realism of the sculptural form, just as Picasso would do in Guernica.

Guernica was on a scale not dissimilar to many altarpieces in churches and chapels across Spain. Perhaps it was closest to the scale of the epic tapestry series woven in Flanders but imported in astonishing numbers, considering the extravagant cost, to Spain from the 15th century on. Like theatre backdrops, they set the scene. Often, as in Zaragoza, they were brought out into the open to create dramatic corridors and stage sets. Picasso, of course, had experience in painting backdrops for ballets, like his work on Léonide Massine’s and Manuel de Falla’s El Sombrero de Tres Picos in 1919, now on display at the New-York Historical Society.

What I am sure invaded Picasso’s mental space was the much richer tradition, so celebrated in Spain, of sargas. These are large, loose canvases, flexible enough to be rolled up, and decorated with both sacred and profane subject matter. They are traditionally hung up to celebrate feasts and special holy days; to decorate a pantheon or funerary chapel; or, just for sheer practicality, to keep the dust out of organ pipes or the draught out from a creaky old walnut door. Economical to produce, as the linen or jute support was primed and prepared only with rabbit skin glue, sometimes mixed with honey, they were quickly decorated with appropriate subjects. Some sargas were covered with a thin gesso cover, sieved out for smoothness—yeso cernido—but there was always the danger that the paint might flake off. Relatively few sargas with profane subjects have survived; sacred ones, however, by their very nature and status and their continued use, are far more common.

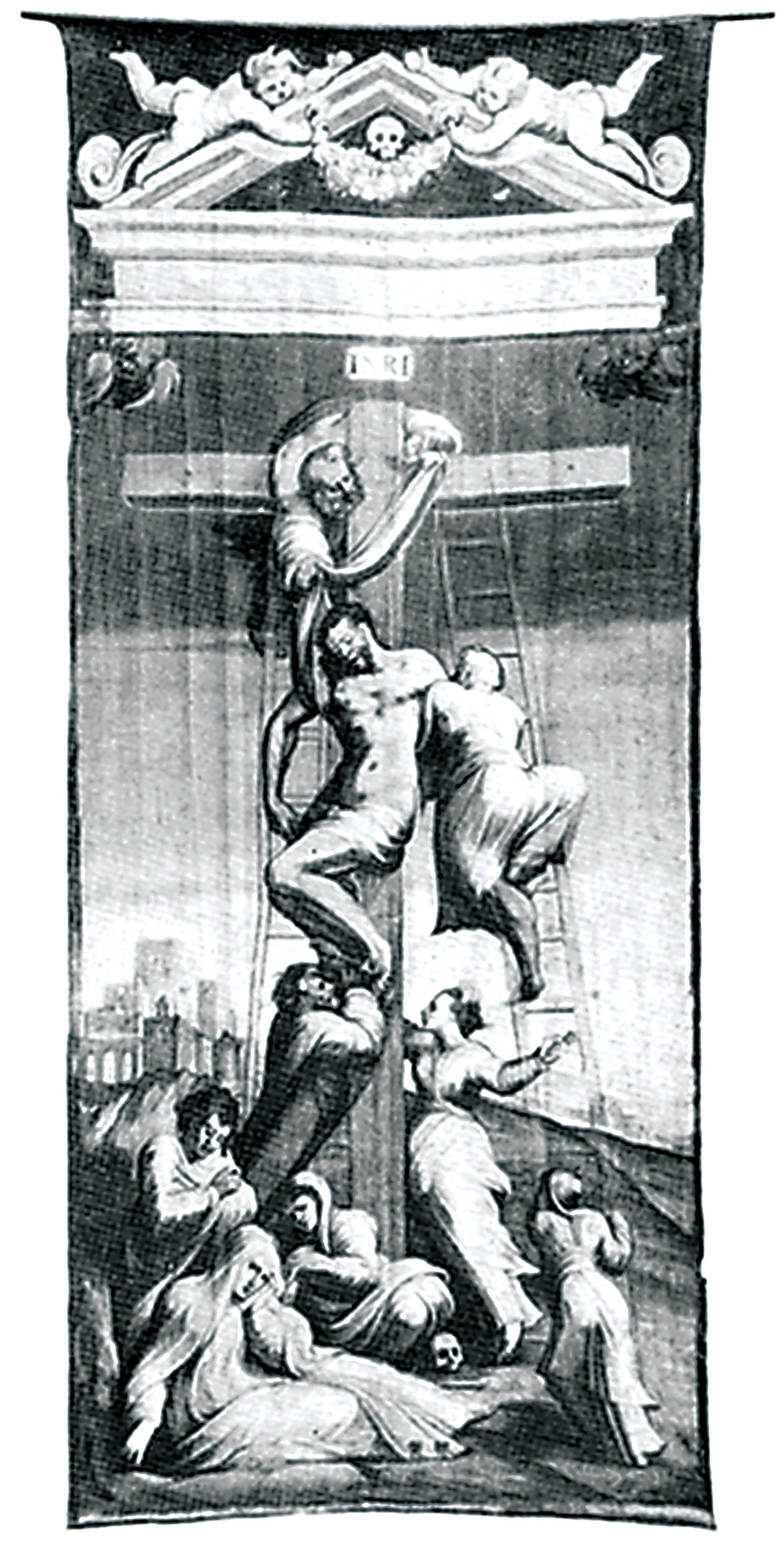

In 1936, one of the most celebrated sargas, painted by Juan de Villoldo in the 16th century and depicting the descent from the cross, entered the collection of Madrid’s Museo Municipal. Interestingly, allowing for the subject, sargas often mixed architectural and landscape motifs to create a sombre theatricality. Sometimes the grisaille palette creates an almost ghostlike x-ray appearance as the gentle folds add a further sense of movement and disquieting reality. I am not trying here to find a single source for Picasso’s Guernica—a single sarga he may have seen—but instead provide a cultural matrix that was central to Spain’s and Picasso’s notions of public art.

Propaganda piece The profession of sarguero was highly respected and protected by guild status, alongside painters and sculptors. But where the sargueros really came into their own was with the production of sargas for Lent and Holy Week. Sargas set the tone and mood for communal reflection that focus on the tragedy of Christ’s passion. Holy Week is the absolute centre of the Catholic year but also the high point of religious theatre. The Christmas belens—the nativity scenes—are an essentially static art form. Holy Week, on the other hand, is alive, as its rhythmic march leads us towards Good Friday in a profounder pattern of mourning. In many Spanish cathedrals the theatre starts on Palm Sunday as the gold embossed Baroque altars, jammed full of statuary, are covered up within minutes by an ashen veil. A sombre sarga depicting the descent from the cross is hoisted up high on pulleys like the sail of a ship. There are two wonderful examples in Burgo de Osma and Zamora cathedrals. The sarga is there for contemplation and to set the spiritual tone of abject loss that is beyond consolation and literally lost for words. The climax in the life of a sarga is when it is slowly lowered down like a gigantic shroud on Easter Sunday, rolled up and put to sleep, as the high altar is revealed in all its glory to proclaim that Christ has risen, once again, triumphantly from the dead.

Picasso’s choice of jute as opposed to any other support for Guernica and his understanding that the work was a propaganda piece destined to travel suggests that he understood full well the sarga tradition; it was in his Spanish Catholic DNA. Incidentally, when Guernica finally arrived in Manchester in 1939 the art students improvised quickly and nailed it straight onto the wall, like the sargas in Spain. Whether Picasso knew that his giant banderole had been treated like this, or whether he would have cared, we do not know, but as yet it had not become the priceless icon we recognise it as today.

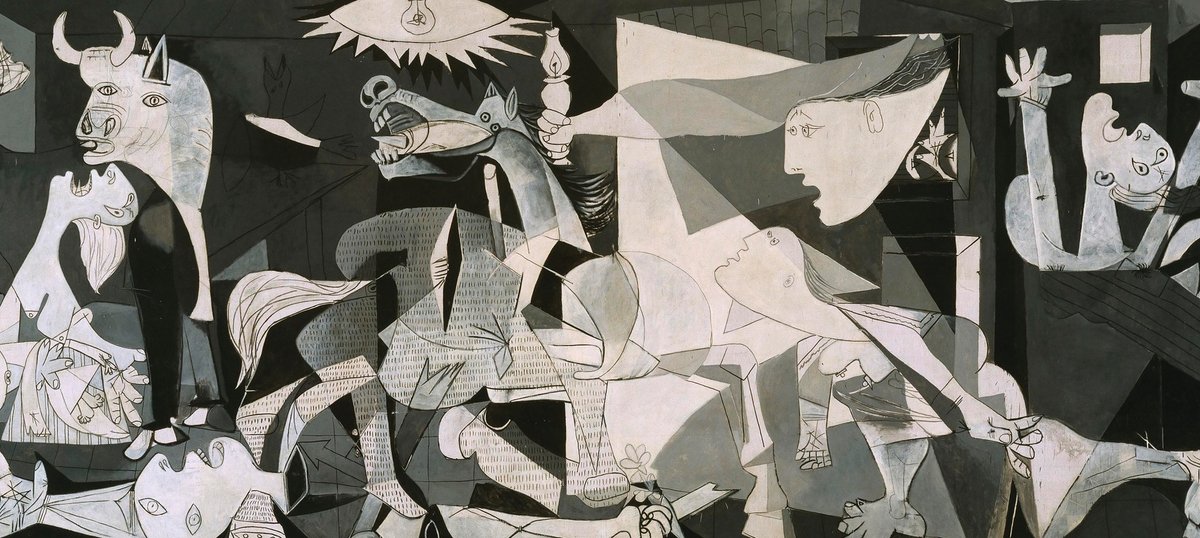

What Guernica depicts, then, is the horror and destruction of ritual and faith by throwing everything we know about the bullfight and religious theatre and turning it on its head. The narrative has been disrupted, the thread of logic cut. Homes are destroyed and public spaces defiled. Picasso was always insistent that characters in his paintings had autonomy and a life of their own. His wife Olga could be transformed into a spiky-toothed monster; Marie-Thérèse Walter was forced to wear Maar’s favourite hat; people might even change sex. His characters are actors on a stage and, like puppets, have no control over their destiny. They can be pulled and pushed and drowned under paint. The claustrophobia and horror of Guernica is contained and made accessible because it is essentially a theatre set. Biblical in its ambition, Guernica is for our time, and for future generations, a terrifying rendition of the slaughter of the innocents, played out on a flimsy wooden stage.

• Guernica: the Biography of a 20th-Century Icon, Gijs van Hensbergen, Bloomsbury Paperbacks, pp288, £12.99

• Pity and Terror: Picasso’s Path to Guernica, Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid, 5 April- 4 September; museoreinasofia.es

The magpie artist: works that may have paved the way to Guernica Guernica’s influences are likely to have included works from a range of disciplines across the centuries