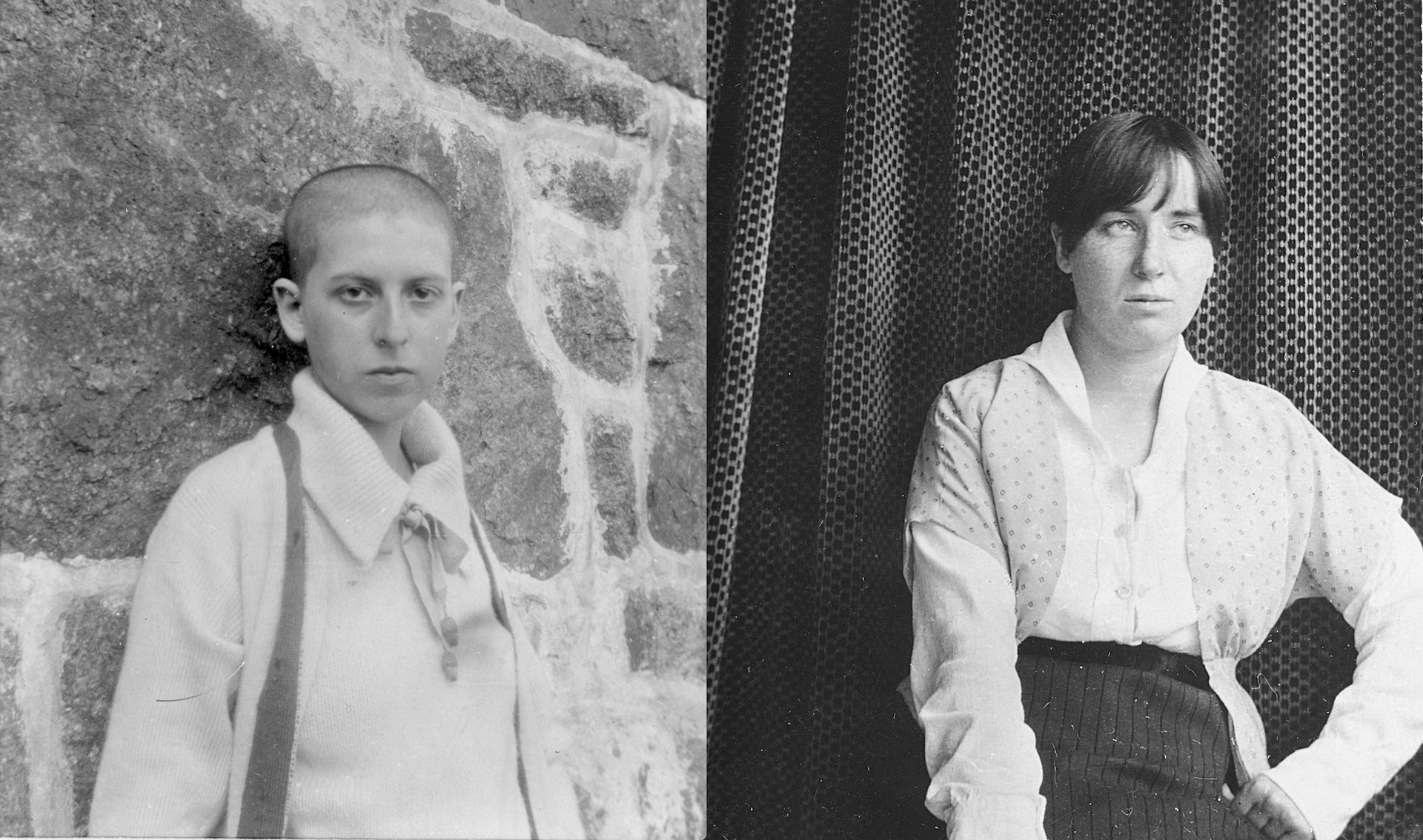

The story of how the artists Lucy Schwob and Suzanne Malherbe—better known by their alter egos Claude Cahun and Marcel Moore—outfoxed the German invaders of the British Channel island of Jersey during the Second World War, is laid out in a new book by Jeffrey H. Jackson, a professor of history at Rhodes College in Memphis. The artist couple were, according to the Paper Bullets book sleeve, “lesbian partners known for cross-dressing and creating the kind of gender-bending work that the Nazis would come to call ‘degenerate art’”.

Lucy Schwob and Suzanne Malherbe, also known as Claude Cahun and Marcel Moore Courtesy of the Jersey Heritage Collections

Jackson describes how the pair, who were “always, to some extent, performing”, thrived in 1930s Paris, developing their artistic practice centered on gender fluidity. “Given her fluid self-presentation, Lucy knowingly acted out numerous personae as Cahun, with Suzanne/Moore as her audience,” Jackson writes. “In their work together, especially with their camera, they raised questions about sexuality, with Lucy sometimes appearing to be without gender and, at other times, a masculine/feminine hybrid.”

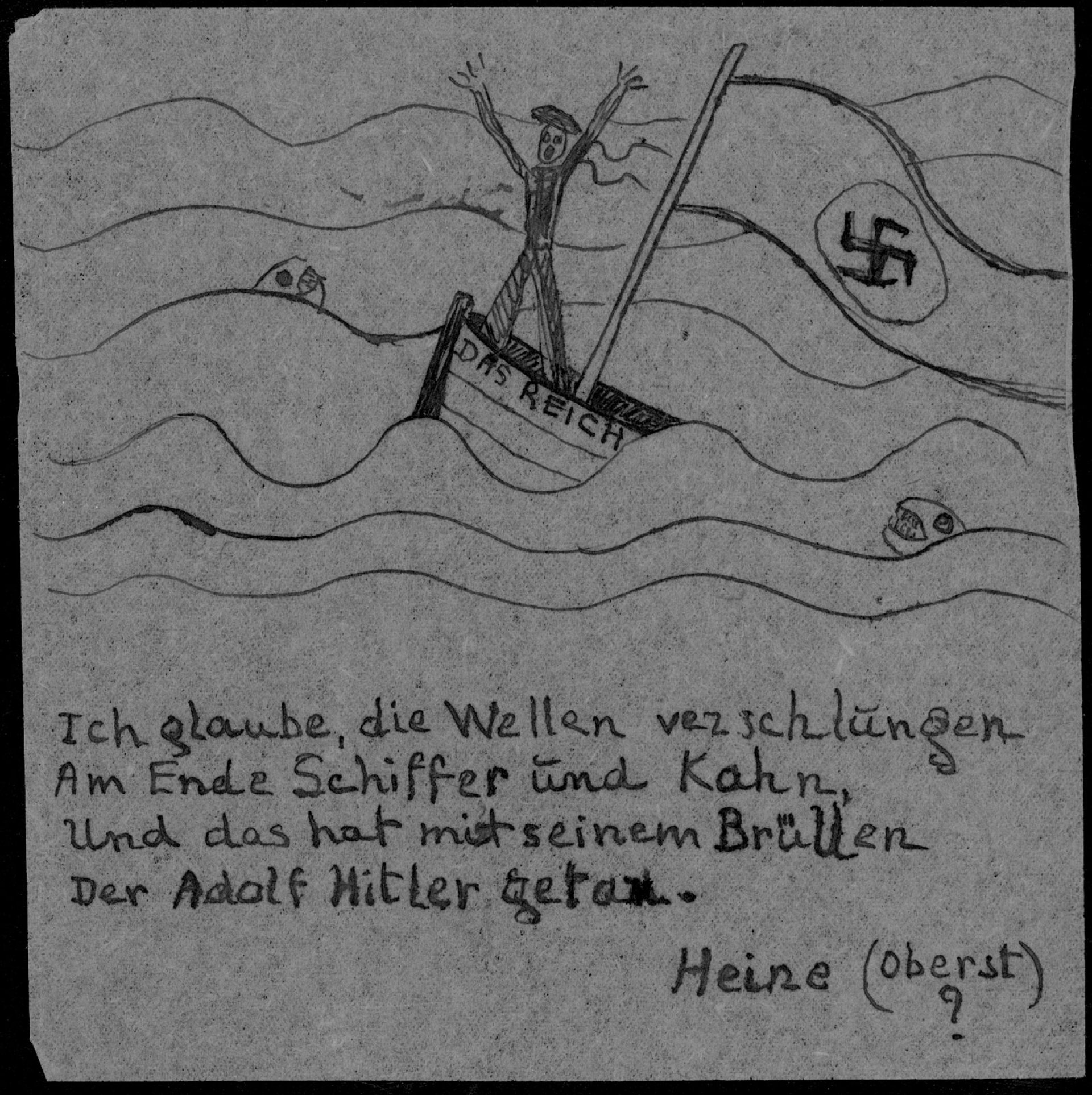

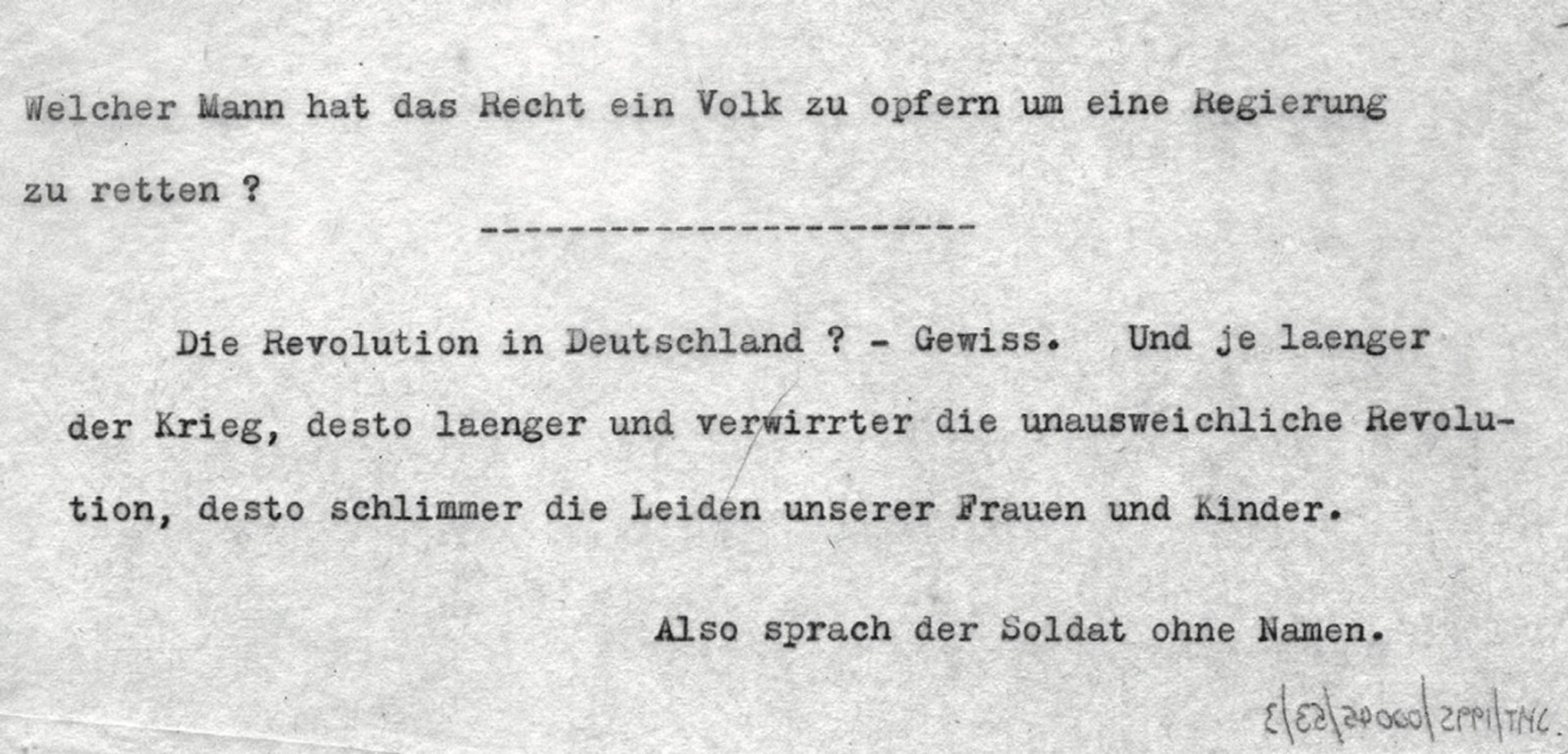

The couple moved to Jersey in 1937 and when the island was later invaded by German forces during the war, they began their own unique types of resistance. Drawing on their artistic experiences, Schwob and Malherbe created subversive, satirical Dada-esque messages, covertly distributing these “paper bullets” all over Jersey. For instance, they created texts mocking Hitler’s slogans made famous in his biography Mein Kampf, jamming them into mailboxes or tucking the them on car windshields.

The extract below outlines how their activities sought to sow seeds of confusion amongst the occupying German troops.

German soldiers marching through the Jersey capital of Saint Helier Courtesy of the Société Jersiaise Photographic Archive

In a postwar letter, Lucy described the day that she and Suzanne came upon a photograph in a German magazine that showed a regiment of soldiers on the march. This presented them with a new kind of opportunity. When they got home, they unwrapped the scarves from around their heads, unbuttoned their overcoats, and placed the photo on the table. “The soldiers in the photo are marching vigorously,” Lucy wrote. “They’re swinging their arms as they move, but their legs are very boring, and their boots are covered in mud. It’s as though they are stuck in the mud.”

They decided to cut the picture in half, keeping the bottom portion and turning an image of Nazi strength into one of a muddy mess. Then, with red paint, Lucy wrote what she called “our jingle”—ohne Ende [without end]—across it, rendering the soldiers as endlessly trudging through the muck. Not satisfied, she removed an old photograph she had of Oscar Wilde and his lover, Alfred Douglas, from its cherished frame. She replaced this photo with that of the cropped soldiers and beheld the ironic contrast between the lovely frame and the grimy image it now held.

One of the “paper bullet” notes, the artists’ version of Heinrich Heine’s poem ‘Die Lorelei’ Courtesy of the Jersey Heritage Collections

Edna had heard that the Germans were about to commandeer a nearby abandoned house as sleeping quarters for the soldiers. It was the perfect place to complete the joke, Lucy thought, and that night Suzanne crept inside the dark, empty house and found the perfect spot to bang in a nail. The next day, the light from one of the windows would hit the photograph just right.

The soldiers might not immediately see the image, but when they did, each would likely think that perhaps one of the other men had hung it. Such a thought might sow confusion and mistrust in their ranks, Lucy and Suzanne hoped. A few days later, they went back to the house and found a place where they could discreetly observe the German soldiers. From their nearby hiding place, the women watched the occupiers going in and out of the house, and they couldn’t help giggling, not quite believing that they had gotten away with their very serious joke. What did the soldiers inside the house think about the mysterious photograph of endless, meaningless marching? they wondered. Were these men contemplating the thought that Hitler’s war would never end?

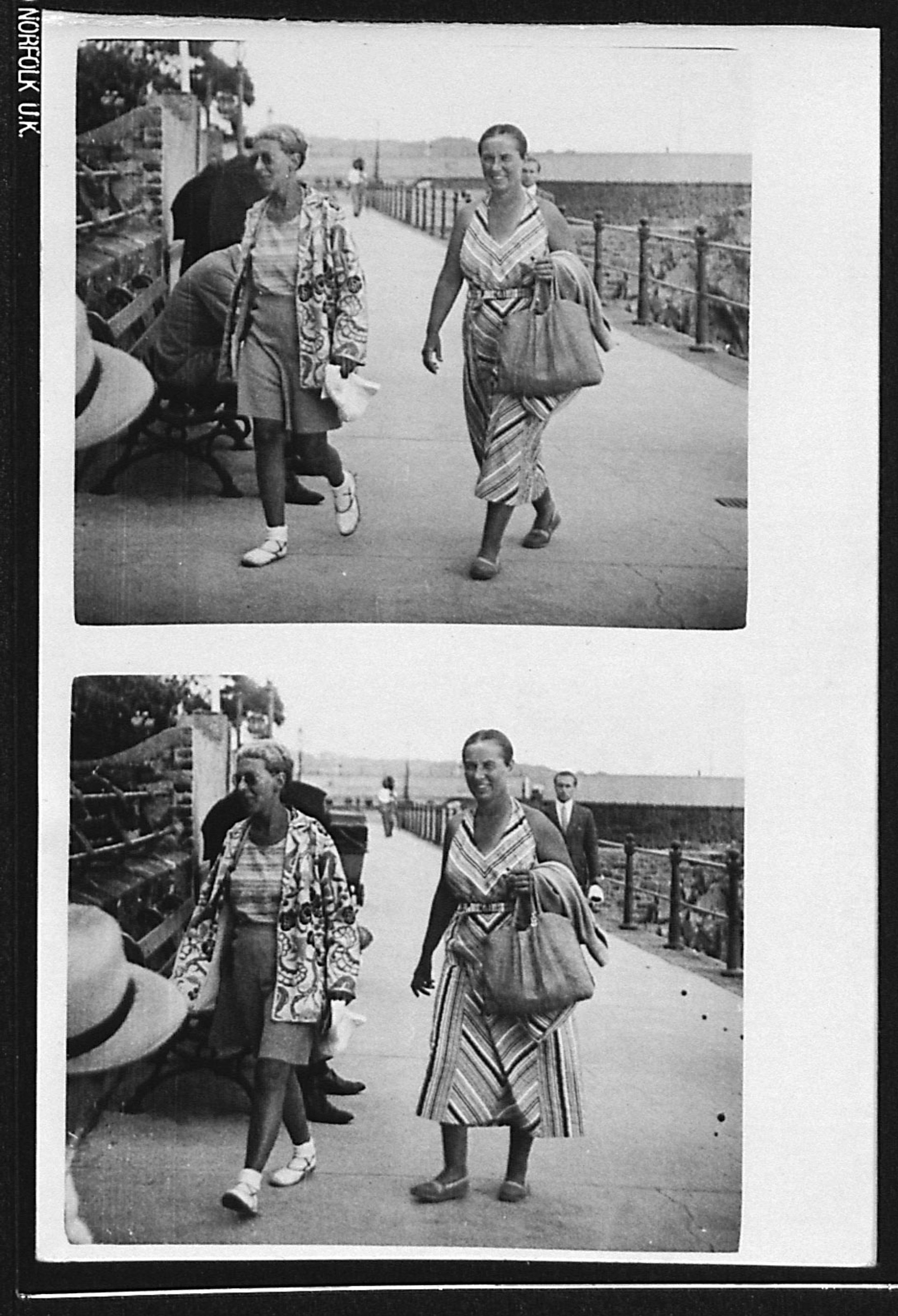

Lucy Schwob and Suzanne Malherbe walking in Jersey Courtesy of the Jersey Heritage Collections

This little adventure gave the women the taste for doing more with photographs. When they went shopping in St. Helier, Lucy bought copies of the glossy illustrated propaganda magazine, Signal. It came in an English version for the civilians, but Lucy chose the German-language edition produced for the troops. They flipped through page after page until something jumped out—an image, a map, some text. Once they had collected enough material, they cut the pages up and put the pieces back together as a photomontage, like the sort Suzanne had made in Paris for Lucy’s book. Lucy believed that working with the German words might also help her learn a bit of the language, making it easier to create more slogans or jokes. “The work was long, very bad for my eyes,” Lucy remembered about her poor vision. “I could not read with one of them, not even with any kind of glasses.”

Once they finished the photomontage, they went back to town and looked for a newsstand. Here, teamwork was essential. Suzanne would pick up a copy of Signal and begin leafing through it, acting as though she were simply reading the magazine. Lucy kept an eye on the newsagent and the other customers while also watching for police. There were too many ways to draw suspicion, so the timing of the drop was crucial. When Lucy gave her the sign, Suzanne pulled the photomontage out of her bag, quickly slipped it in between the pages of the magazine, and placed it back on the newsstand. Then they walked away casually, not looking back until they were at a distance.

One of notes: “Who has the right to sacrifice a people in order to save a government? . . . And the longer the war, the longer and more confused the inescapable revolution, the worse the sorrows of our women and children. Thus says the soldier with no name” Courtesy of the Jersey Heritage Collections

Sometimes, if they were being watched or if too many other customers were around, they had no choice but to buy the magazine, even though the newsagent might wonder why they were interested in a German-language publication. They would then carry it to the toilet of a nearby cafe. Once behind the locked door, Suzanne put the collage between the pages. Then they left the cafe, went to another newsstand or bookshop, found the stack of identical magazines, and placed their creation underneath several other copies.

• Paper Bullets, Jeffrey H. Jackson, Algonquin Books, 326pp, $27.95 (hb) (reprinted by permission of Algonquin Books; © 2020 Jeffrey H. Jackson)