This article was featured in our free monthly Book Club newsletter. Sign up here for features, exclusive extracts, author interviews and art world recommendations sent straight to your inbox

As a tall, young, athletic SS officer with fluent French and a doctorate in art history, Bruno Lohse captured Hermann Göring’s attention during one of his visits to the Jeu de Paume art gallery in Paris, where the Reichsmarschall would quaff champagne and select paintings looted from French Jews. The art would then be transported by Göring’s private train to his country estate outside Berlin.

Lohse became Göring’s agent in Paris, charged with helping Adolf Hitler’s number two to amass his vast store of stolen art. He oversaw operations at the Jeu de Paume, where the Nazis stored art looted from Jews by the infamous Reichsleiter Rosenberg Taskforce (known as the ERR).

Like many key Nazi looters, Lohse escaped conviction after the Second World War, although he did spend several years in prison, in Nuremberg and in France. On his release in 1950, living in Munich, he became part of a shadowy network of former Nazis who continued to deal in looted art, largely untroubled by law enforcement or public attention.

“Lohse ranks in the top five all-time art looters… a skilled liar, dissimulator, schemer”Jonathan Petropoulos, author

Jonathan Petropoulos first met Lohse in 1998, when the dealer was 87. More than two decades later, Petropoulos has written what will surely be the definitive biography, Göring’s Man in Paris: The Story of a Nazi Art Plunderer and his World, published this month.

Petropoulos is the author of several authoritative, lucidly written and important books about the arts in the Third Reich, including The Faustian Bargain: The Art World in Nazi Germany. He is an enterprising, investigative historian of the kind journalists can feel a kinship with. He describes, for example, turning up with begonias on the doorstep of the widow of a long-dead Nazi art looter in the 1990s (she invited him in, offered him coffee, and talked).

Bruno Lohse, with SS insignia on his sweater, an unknown colleague and two women in occupied Paris

He penetrated deep into Lohse’s world—a disquieting but intriguing cosmos of aging Nazis nostalgic for the “good old days”, of kaffee und kuchen in luxury hotels, of secretive Liechtenstein foundations, and of Swiss bank vaults stuffed with stolen art.

It was a Zurich bank vault that catapulted Lohse back into public view in 2007, just weeks after his death at the age of 95. The Swiss prosecutor seized a vault controlled by Lohse in the Zürcher Kantonalbank. Its contents included Le Quai Malaquais, Printemps (1903), a painting by Camille Pissarro that the Jewish family from whom it had been looted in Vienna had been trying to trace for 70 years.

Together with a dealer friend of Lohse’s, Peter Griebert, Petropoulos had previously engaged in efforts to return the painting to Gisela Bermann Fischer, the heir of the family. Because Griebert and Petropoulos asked for a percentage of the painting’s value for recovering it, she reported these efforts as attempted extortion to law enforcement.

Griebert was investigated but never charged or convicted, Petropoulos writes. The author, who was never investigated by police, says he received no compensation from the eventual restitution and sale of the painting. But these tortuous events, described in the book, compelled Petropoulos to step down as the director of the centre for Holocaust studies at Claremont McKenna College, California, in 2008.

Hermann Göring and Bruno Lohse looking at a book on Rembrandt in the Jeu de Paume Archives des Musées Nationaux/Archives Nationales.

Petropoulos portrays himself as a victim of Griebert’s intrigue, and says he did not know the painting was controlled by Lohse. Still, he indirectly admits it was a mistake to get embroiled in this affair, citing the lawyer Randol Schoenberg’s comment that academics like Petropoulos are invaluable for provenance research “but out of their league if they try to negotiate a work’s return”.

Petropoulos appears unsure about whether he got too close to Lohse. In the book’s prologue, he asserts: “For me, our meetings were strictly fact-finding missions… I do not want to give the impression that I befriended him or in any way seem to whitewash his deeds.” By the epilogue, he has apparently changed his mind. “Yes, Bruno was a kind of friend, and that is problematic for a historian of the Third Reich,” he writes.

Regardless of this awkward friendship, Göring’s Man in Paris is far from a whitewash. Perhaps the 13 years since Lohse’s death needed to pass for the author to view him with detachment. Petropoulos does not mince his words—Lohse, he says, “ranks in the top five among history’s all-time art looters”. He was, the writer says, “a skilled liar, dissimulator, and schemer”.

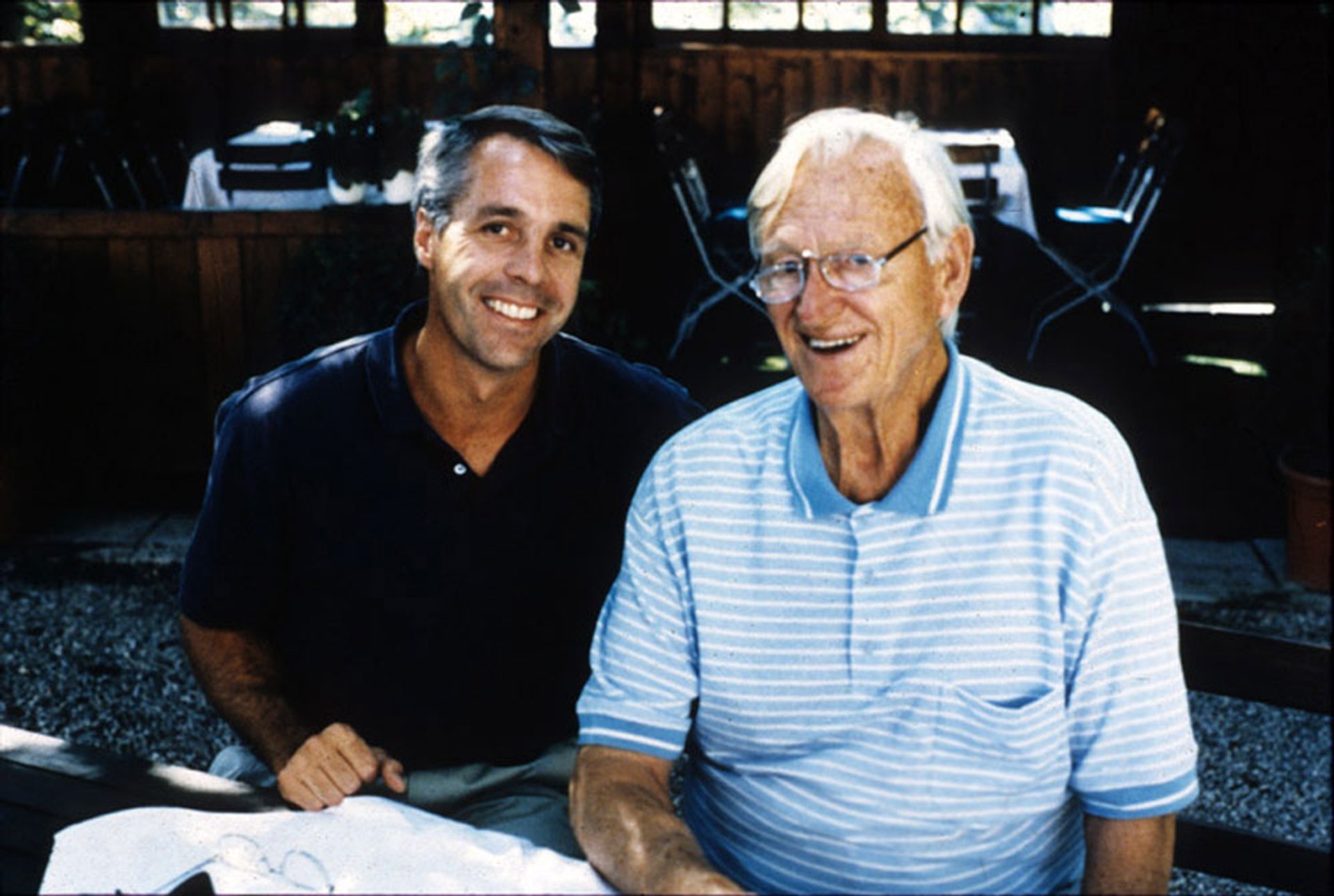

The author Jonathan Petropoulos with Lohse on the occasion of their first meeting in Munich in June 1998

The book describes in meticulous detail how this dashing SS officer, living a life of luxury with a chauffeur-driven car in Paris, organised 18 exhibitions of looted art for Göring at the Jeu de Paume, helped him commandeer more than 700 paintings from the ERR, and acquired many more from other dubious sources. Lohse tracked down hidden collections belonging to Jews who had fled or been deported and took part in raids to seize their collections.

How he escaped conviction for war crimes is something of a mystery, but Lohse seems to have attracted important allies—including, bizarrely, some of the American Monuments Men who interrogated him in Nuremberg—and he assembled a crack defence team for his trial.

He set himself up as an art dealer in Munich to supplement the benefits he received from the German government as a former “prisoner of war”. Petropoulos’s research sheds important light on the post-war networks, radiating from Munich to Switzerland, Paris and even the US, that allowed Lohse to stay in business. His Munich circle encompassed Göring’s daughter Edda and the Reichsmarschall’s former secretary, Gisela Limberger.

Lohse’s devotion and loyalty to Göring remained undiminished until the end of his life. His treasured mementoes included his Nazi party membership card and a letter from Göring written in Nuremberg testifying that he had repeatedly asked to be excused from his duties in Paris to return to the front. Because it was signed in Göring’s own hand so close to the end of his life, it became a “sacred relic” for Lohse, Petropoulos writes. Almost daily, the elderly Nazi thief would pore over these keepsakes and photos of his days in the ERR, a time he still viewed as the high point of his career. It is a chilling image.

One question still unanswered is how much looted art he got away with. Petropoulos describes paintings by Emil Nolde and Gabriele Münter and a clutch of Dutch Old Masters hanging in Lohse’s Munich apartment. He suspects Lohse kept for himself some of the works he acquired for Göring.

Tantalisingly, the book’s appendix lists 47 works that were in Lohse’s possession when he died or sold shortly before his death—among them paintings by Lucas Cranach, Camille Corot, Pierre-Auguste Renoir and Jan Brueghel. Provenance research into these works has never been published and they have been distributed among Lohse’s many heirs, or sold discreetly. Perhaps one day we will find out who they once belonged to.

• Göring’s Man in Paris: The Story of a Nazi Art Plunderer and His World, Jonathan Petropoulos, Yale University Press, 456pp, $37.50, £25 (hb)