In 1968, in the off-Broadway Bouwerie Lane theatre, Brigid Berlin took to the stage for one of the avant-garde performances she titled Brigid Polk Strikes! Her Satanic Majesty in Person.

She phoned her friend Huntington Hartford—co-heir to the A&P grocery store fortune and founder of the short-lived Huntington Hartford Gallery of Modern Art in New York—and told him she needed help to have an abortion. She held the microphone by the phone’s receiver, amplifying his voice over the hushed crowd. As the audience tried to suppress their laughter, Berlin regaled Hartford with a heartbreaking story of how she had realised she wasn’t simply overweight, she was accidentally pregnant. She urgently needed money for a back-room termination. He promised to give her whatever cash she needed. Berlin asked her audience to wait, ran from the theatre, jumped in a taxi, collected the money from Hartford's uptown home, and then returned to share her new $100 with the audience.

With or without Warhol, Berlin was a highly creative, experimental and searingly authentic chronicler of herself and her body, of her friends and community and of the times she lived in

The story is typical of an artist best known for her association with Andy Warhol, but who may now be recognised as an artistic pioneer in her own right. For, with or without Warhol, Berlin was a highly creative, experimental and searingly authentic chronicler of herself and her body, of her friends and community and of the times she lived in. She can now be seen as a trailblazer for the body politics and projected self-representations that are de rigueur across our culture.

Berlin came from an upper-crust New York family. Her father was Richard E. Berlin, the president of Hearst publishing house for 30 years. Her mother was a well-known socialite on the Upper East Side, known to her friends as “Honey”. Her parents’ Fifth Avenue apartment was a hang-out for political power, where the future Presidents Lyndon B. Johnson and Richard M. Nixon and the FBI director J. Edgar Hoover were dinner guests.

But Berlin, in her father’s words, was a “hostile debutante”. As a teenager, she was supposed to attend the parties of her parents’ high-society circle. There, she was expected to meet a suitable suitor. And, as such, she was supposed to be thin.

In an interview with Gary Comenas for the website Warhol Stars, Berlin remembered childhood trips to Paris with her mother. “My mother used to go to Papillon and the Colony and have three asparagus spears. She was a one-spoonful gal,” she said. “Not me! She used to take us to Paris, but she spent her whole time in couture fittings, so my sister and I ran around Paris eating ... They all ate like birds, so I started to sneak the uneaten food in the middle of the night.”

Her mother sent her to a doctor, who prescribed amphetamines in the belief it would promote the mentality needed for weight loss. Instead, the good doctor provided Berlin with her first experience of hard narcotics. Berlin began to rebel. She drank heavily and was expelled from numerous schools. Speaking in the documentary Pie In the Sky: the Brigid Berlin Story (2000), she says her father used to donate paintings to a Catholic school she briefly attended to prevent herself and her sister, Richie, from getting thrown out.

After finishing her schooling, Berlin was expected to attend a “coming-out” debutante ball — she invited the family electrician. Then, at the age of twenty-one, she married a blue-collar and openly gay window dresser. She did so as a provocation; perhaps her first avant-garde performance. She soon sought a divorce and disappeared into New York’s underground art scene, ending up as a receptionist of sorts at Andy Warhol’s Factory in 1964.

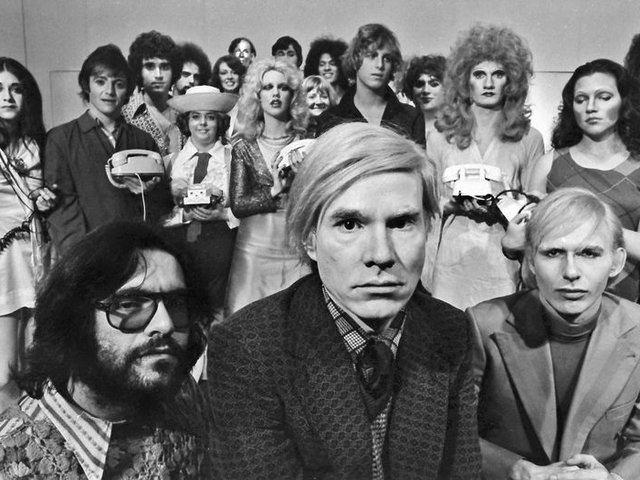

Berlin was a mainstay at the famous studio and, over the years, became Warhol’s best friend— “the only person who could yell at him,” Vincent Fremont, a founding director of the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, told the Los Angeles Times. “They were like a married couple but they weren’t married.”

Brigid Berlin (left), Andy Warhol and friends at the Factory, New York City Steve Schapiro

She was also a regular in Warhol’s films. Dedicated followers of the Factory will remember Berlin from Warhol’s 1966 film Chelsea Girls. Berlin is referred to in the film as Brigid Polk, a “polk” being the Factory’s slang name for a sizeable injection of amphetamine. Warhol records Berlin— true to her nom de guerre—injecting herself with speed in the midst of the action before having a live sexual encounter with another woman.

Part of the reason Berlin never received recognition as an artist was that she never considered herself to be one. In fact, she actively rejected the moniker. She would relay an anecdote of Warhol offering, as a Christmas present, one of his paintings, and she, in response, telling him to buy her a new vacuum-cleaner instead.

Yet Berlin was an obsessive documenter of herself, her surroundings, and of the community of people—many of them now historic figures—who frequented the Factory. She recorded conversations by cassette and routinely took Polaroids. From 1967 to 1974, she recorded daily, and took huge pride in the quality of her recordings—"I always had the best microphones,” she once said.

Later in life, she found in her archive images of Patti Smith, Dennis Hopper, Leonard Cohen, Diana Vreeland, Richard Avedon, Paloma Picasso, the Velvet Underground, Robert Rauschenberg, Jasper Johns, John Chamberlain and Larry Rivers. Yet many of her images didn’t survive, as she never placed a huge amount of value on their continued existence. “No picture ever mattered,” she once said. “There was never any subject that I was after. It was clicking it and pulling it out that I loved.”

Berlin spent much of her adult life in a room in the George Washington Hotel near Gramercy Park. before moving to an apartment in 1986. In her seventies, and before complex health problems largely confined her to her bed, she was a well-known character in the neighbourhood, often seen in the park with her pug dogs. She also acquiesced to pleas from friends to digitise her chaotic archive. The resulting book, Brigid Berlin: Polaroids, was released in October 2016 by Reel Art Press. In an introduction to the volume, Bob Colacello, a former editor of Interview magazine, wrote: “Brigid’s need to rebel has always been matched by her need to document her rebelliousness, and the overlapping of these two compulsions is what gives her work meaning beyond its curiosity value. In recording life, she captured our times.”

- Brigid Berlin, born 6 September 1939, died 17 July 2020