The Tate briefly flirted with the idea of splitting in two and setting up an entirely separate Museum of Modern Art, inspired by the success of MoMA in New York. This was in the early 1990s, before the gallery decided to remain a single institution with two London venues: Tate Britain and Tate Modern.

The behind-the-scenes efforts of Nicholas Serota, the Tate’s director from 1988 and 2017, to create Tate Modern are revealed in the gallery’s trustee minutes for 1991-92, which have been opened up for The Art Newspaper. Serota was concerned at the Tate’s lack of display space at the time, particularly for contemporary art. Realising that there was little chance of a major expansion at Millbank, the site of the then Tate Gallery, he embarked on a search for a new home for international art (the collection comprises British art from the 17th century and international art from around 1900).

The Tate’s board held its first serious discussion on the subject in September 1991. One of the trustees, the cosmopolitan banker Gilbert de Botton, opposed any split, arguing that a separate gallery of British art “in the context of increasing Europeanisation might no longer be appropriate”. Other trustees said that “national cultural identity need not be abandoned in the search for political and economic union”. (The UK government would sign the Maastricht Treaty, which created the European Union, in February 1992.)

National cultural identity need not be abandoned for political and economic unionTate trustee

Serota, meanwhile, was considering two possible sites for the new gallery—at King’s Cross, near the present Central Saint Martins art college, and in Docklands, east of Canary Wharf.

The board held a more detailed debate in January 1992. The artist Christopher Le Brun, now the president of the Royal Academy of Arts, had initially opposed the move to a new site but then changed his mind, as long as British art would still be displayed in an “exciting way”. Another artist-trustee, Michael Craig-Martin, called for a good presentation of “living artists”.

Domestic politics then reared its head. With a general election on the way that April, the Tate’s chairman, the businessman Dennis Stevenson, warned that a new government might “discourage” ambitious plans for a gallery of Modern art. Serota responded that “any incoming government would be subject to bids from many quarters”, and that the Tate should be among them.

One proposal was for “two entirely separate museums”. Stevenson was not keen, pointing out that the Tate had begun as an offshoot of the National Gallery and that the institutions had “not always” worked well together. Serota thought separation was “the most radical solution” but still demurred. It was “extremely unlikely” that the government would be supportive, he said, because of the cost and risks.

An alternative taken more seriously was to open a temporary museum of Modern art for eight to ten years, while a permanent site was identified and developed. The interim museum would probably have been in the former Billingsgate fish market, in the City. This scheme was later dropped, as trustees expressed fears it would be “marooned” as a semi-permanent arrangement.

Returned to power in the general election, the UK prime minister, John Major, appointed David Mellor as the secretary of state for the newly created Department for National Heritage, which he famously nicknamed the “ministry of fun”. Mellor developed cordial relations with the Tate, but became mired in controversy over an extra-marital affair. The trustees hoped the gallery would avoid government funding cuts if he “survived the latest press campaign”. Mellor resigned a few months later, but the Tate pressed ahead to establish a Tate Gallery of Modern Art.

The official announcement came on 15 December 1992. Two days later, the National Lottery Bill was published, creating the Heritage Lottery Fund and the Millennium Fund. Serota’s timing was perfect. Tate Modern, as it was eventually named, opened in 2000. Last year it welcomed 5.7 million visitors, more than double the 2.8 million who went to MoMA in New York.

Nicholas Serota looks back: "I was worried about appearing isolationist in regard to British art"

On the birth of Tate Modern, Nicholas Serota, who retired as the Tate’s director in 2017, says today he was concerned about dividing British and international art at a time of increasing European integration.

“I was always worried about appearing isolationist in regard to British art,” Serota says. He went ahead, he recalls, because the strength of the Tate’s collection meant it was still possible to show the links between British and international art. The museum briefly considered keeping only pre-1900 British art at its Millbank site, but Serota “felt that this would result in an even greater isolation and leave Tate Britain without a connection to living artists”.

The idea to set up two entirely separate institutions with independent boards was “more a theoretical possibility”, he says, since it would have required separate marketing, press and development offices, and therefore increased costs.

Along with King’s Cross and Docklands, Serota considered Battersea and the Hungerford car park on the South Bank as locations for the future gallery of international art. It was not until March 1993 that he first viewed the disused Bankside power station, which was chosen the following year.

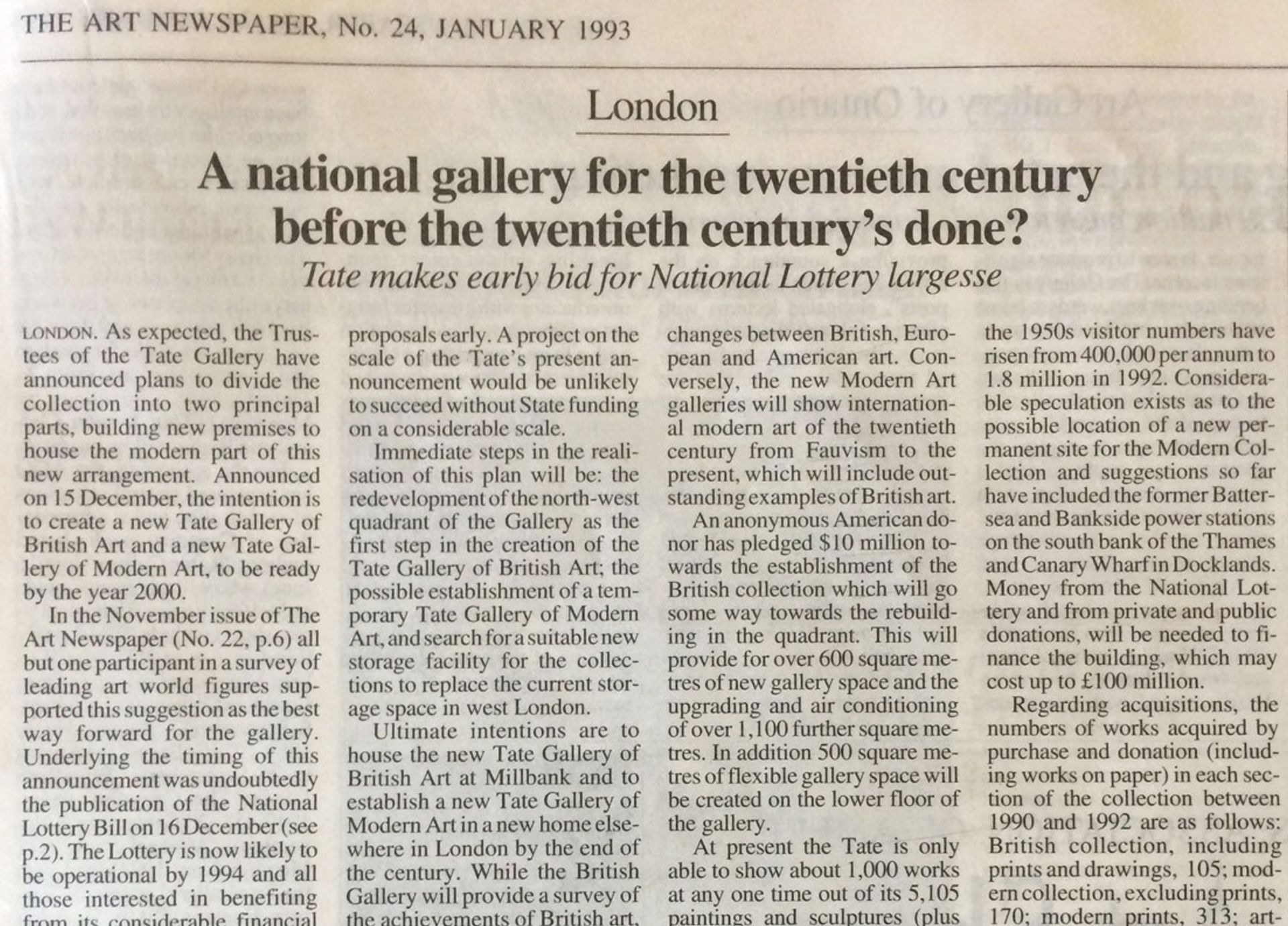

How we reported on the Tate's plans for a Modern Art Gallery in January 1993 The Art Newspaper