"Until very recently, the idea that women have always made art was rarely cited as a possibility. Yet they have, and of course continue to do so, often against tremendous odds and restrictions, from laws to religion and convention, the pressures of family and public disapproval," writes Jennifer Higgie in her illuminating new study dissecting why women have been largely shut out of art history (The Mirror and the Palette: Rebellion, Revolution and Resilience: 500 Years of Women’s Self-Portraits).

Higgie's clever thesis looks at self-portraits as a springboard, giving fresh insights into brilliant artists such as Frida Kahlo, Loïs Mailou Jones, Amrita Sher-Gil, Suzanne Valadon, Gwen John, Artemisia Gentileschi and Paula Modersohn-Becker. The extract below is from the chapter “Easel”, which focuses on the Italian artist Sofonisba Anguissola (around 1532-1625), a prolific self-portraitist and, during her lifetime, one of the most famous artists in Europe. Higgie describes the impression Anguissola made on the artist Anthony van Dyck when he painted her portrait in the early-17th century.

Artists travelled from afar to meet and learn from Sofonisba. In 1624 the twenty-five-year-old Flemish painter Anthony van Dyck was invited to Sicily to paint the Spanish viceroy, Emanuel Filiberto of Savoy. (At the time, Spain ruled most of the territories below Rome.) Soon after the artist’s arrival, the island experienced an outbreak of the plague; with no one allowed to leave or enter, Van Dyck was forced to stay for eighteen months in the island’s capital, Palermo.

On 12 July 1624 he visited Sofonisba, now eighty-nine—although Van Dyck records her age as ninety-six—at the Lomellini Palace in Palermo, to paint her portrait. It’s worth quoting at length how he captured the encounter in his sketchbook, as it gives such a vivid portrait of the older artist: interestingly, it was the only meeting he wrote at length about. He observes that she still has:

“... a very sharp memory and mind, being most courteous and although she was lacking in good eyesight because of her old age, she nonetheless found pleasure in placing the paintings in front of her and, with great effort, placing her nose close against the painting, she was able to make out a little of it and took great pleasure that way. In making her portrait, she gave me several pieces of advice: not to raise the light too high, so that the shadows in the wrinkles of old age would not grow too large, and many other good suggestions, and moreover, she recounted the part of her life in which she was recognised as a miraculous painter from life, and the greatest torment she had known was not being able to paint anymore, because of her failing eyesight. Her hand was still steady, without any trembling.”

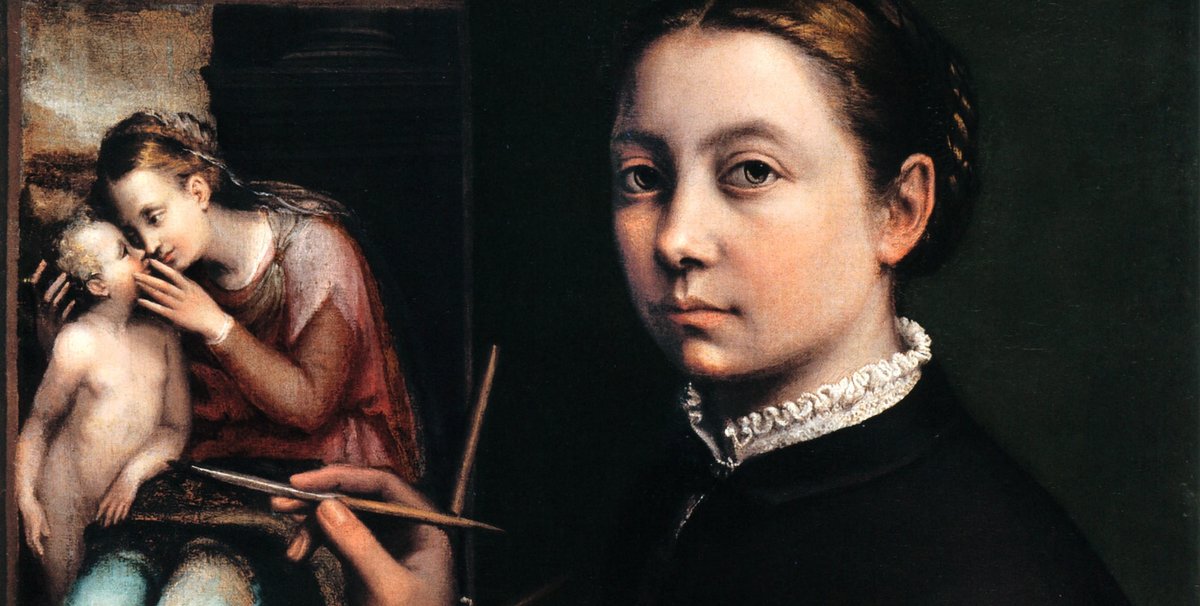

Sofonisba Anguissola's Self-portrait at the Easel Painting a Devotional Panel (1556) Courtesy of The Picture Art Collection/Alamy Stock Photo

Van Dyck’s portrait of Sofonisba shows a steely old woman with fierce, hooded eyes and a resolute gaze. She is dressed demurely in black, with a crisp white ruffle; her head is covered with a white linen veil. As in her early self-portrait, she is surrounded by a dark background: she alone illuminates the void.

The painting is now in the National Trust collection at Knole, Kent. On their website is a brief line of description: ‘This portrait closely resembles the pen drawing, dated 12 July 1624 in Van Dyck’s Italian Sketchbook (British Museum) of the Italian artist Sophonisba [sic] Anguissola at the age of 96. Previously it was known as Catherine Fitzgerald, Countess of Desmond (d. 1636).’ Despite the fame Sofonisba had experienced in her lifetime, after her death even her own face was, for a time, misattributed.

Sofonisba died in Palermo in 1625. Her husband inscribed her tomb with the words: ‘To Sofonisba, my wife, who is recorded among the illustrious women of the world, outstanding in portraying the images of men.’ It is widely quoted that Van Dyck said of his meeting with Sofonisba that he had ‘received more wise advice from the words of a blind woman than from the works of well- known painters’.

• The Mirror and the Palette: Rebellion, Revolution and Resilience: 500 Years of Women’s Self-Portraits, Jennifer Higgie, Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 336pp, £20 (hb)