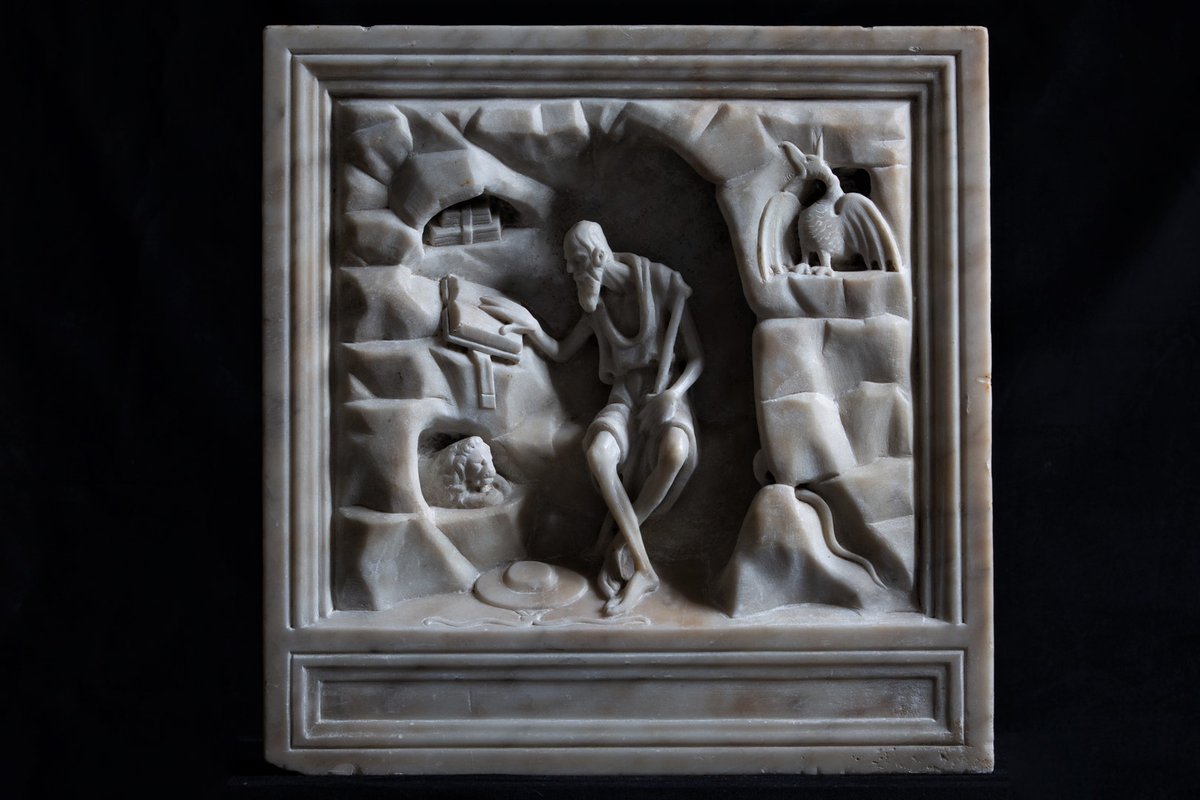

When he was still director of the British Museum, Neil MacGregor told me that his experience at the Sorbonne during the 1968 student riots taught him that politics is behind everything. I was reminded of this when I started to look into St Jerome, one of the easier saints to identify because he always has a lion somewhere about him. We know him in two incarnations: either he is at his desk, dressed as a cardinal and surrounded by books, or he is in a cave, looking emaciated and penitential.

He has just been the subject of what looks to have been a very interesting exhibition in Split, rounding off Croatia’s commemoration of the 1,600 years since the saint’s death in 420AD. Curated by Josip Belamarić, it has for the first time united the 15th- and 16th-century art in Dalmatia about St Jerome, when his cult was at its height and Venetian influence at its strongest. It begins with an altarpiece from Trogir cathedral by Gentile Bellini and then introduces us to artists whose names we may never have heard, but who produced art that is definitely worth knowing, such as Andrea Aleši, whose sculptures are pared away in a startlingly modern manner.

But what is the relevance of St Jerome to Croatia? Wasn’t the cave where he lived and died somewhere in Palestine? A quick Google reveals that he was born in about 342AD, in a place called Stridon, exact location unknown, but in the Roman province of Dalmatia—much bigger than the coastal area of the same name today—but definitely part of what is modern Croatia. He went to Rome to perfect his Latin and Greek studies, later remembering, but bitterly repenting, the parties and the dancing girls he enjoyed there. Drawn to the ascetic life, he went to what is now northern Syria and added Hebrew to his formidable intellectual armoury.

It is to Jerome that the Christian Church owes the Latin translation of the Old and New Testaments, the canonical version right through to the later 20th century, which is why he is considered one of the four, great, early Doctors of the Church, along with Saints Gregory the Great, Ambrose, and Augustine. Like them he is definitely a heavy-hitter, a First XI saint, appointed, as it were, by acclamation rather than the bureaucratic method evolved by the Vatican in later centuries.

Returning to Rome, he was secretary to the pope, which is why he is often shown with a cardinal’s hat even though cardinals did not exist in his day, but in later centuries a papal secretary would usually have held that rank.

Back again in Palestine, he retreated to a cave near Bethlehem for the remaining 34 years of his life. How the lion got attached to him is uncertain, but it happened long after his death and it is probably a conflation of his life with the story of Androcles, the fugitive Roman slave who took refuge in a cave and made friends with a lion by pulling a thorn from its paw.

The exhibition on St Jerome in the Museum of Croatian Archaeological Monuments, Split

Fast forward 800 or so years, and Jerome begins to have his moment. A reform movement in the Church, embodied most successfully by the Franciscan Orders, was looking for its heroes and St Jerome’s asceticism, together with his supposed love of animals, was just the man. He begins to be represented in paintings together with St Francis.

This reforming spirit was religious and inevitably also social, while the next phase in St Jerome’s rise to fame was more to do with what we would call foreign policy, identity politics and an intellectual movement that involved the whole of Europe.

As the Venetians extend their control over Dalmatia, which they bought in 1409, the Dalmatians need to defend their prestige, so St Jerome’s origins get remembered and another old myth is dug up, which is that he invented the Glagolitic script, the most ancient Slavic alphabet, used for the Slavic liturgies. This is, of course, impossible because the Slavs had not yet arrived in Dalmatia in Jerome’s time, but myths are powerful when they are useful.

In 1445 Dubrovnik establishes a feast day in his honour, followed shortly after by the town of Trogir. And what does the first Slavic confraternity in Venice, San Giorgio degli Schiavoni (that is, the Slavs), established in 1451, choose to have painted on its walls by Carpaccio, but the life of St Jerome, “their” saint.

Simultaneously, there is an intellectual movement involving the whole of Europe, but especially Italy, which was about the rediscovery of original Latin and Greek texts and classical art. Known as humanism, these studies were especially alive in the Venice and the towns of its Dalmatian territories, with St Jerome claimed by the humanists as one of their own because of his linguistic learning—not for nothing is he still the patron saint of librarians, translators and archivists. Paintings and sculptures of St Jerome proliferate.

The question is, was he an “Italian” for having been born in a Roman province that was to become Venetian territory for 400 years; or is he a “Dalmatian/Croatian” for having been born in territory that became, and remains, Slavic and is now called Croatia. Astonishingly, for some this is still a burning issue. I have discovered a slightly mad irredentist site on the web with the motto “Ritorneremo” (we’ll be back) that campaigns for the return of “The Italian lands of Istria, Fiume, Dalmatia”, ceded at the end of the First and Second World Wars. It devotes a lot of space to proving that St Jerome was Italian.

The answer, of course, is that Jerome was neither, because neither Italians nor Slavs existed in the fourth-fifth century. He would have said, “Civis romanus sum” (I am a citizen of Rome) and that would have been the end of it. But this kind of question is interesting in so far as it leads us to discover why the fame of certain men and women rises and falls over the centuries, and why art gets created in their honour at certain times and in certain places. Art never existed in the past for art’s sake.

“The Figure of St Jerome and Renaissance Culture in Dalmatia” was at the Muzej Hrvatskih Arheoloških Spomenika (Museum of Croatian Archaeological Monuments), Split, until 30 June. The fully illustrated catalogue is in Croatian, which unfortunately I cannot read, so I was grateful to find Ines Ivić’s thesis online, “The cult of Saint Jerome in Dalmatia in the 15th and 16th centuries”, presented to the Central University in Budapest in 2016.