The Saudi art scene has been buzzing for many years, but now the Saudi government and the country’s 32-year-old de facto leader, Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman Al Saud, have discovered the added value of contemporary art and culture.

His Misk Art Institute is a new cultural organisation with headquarters in Riyadh, led by the pioneering Saudi artist Ahmed Mater, who is only a few years older than his boss. It has been created to encourage art production in Saudi Arabia and enable cultural diplomacy and exchange.

Now that there is suddenly so much money flowing through the kingdom for the promotion of contemporary art and artists, members of the international art world will be waiting to jump on to the bandwagon of cash. Yet one must be aware that Mater is smart enough not to let things go down the same route as Dubai or Abu Dhabi. Already in 2013, he said: “We were consciously reacting against the pressures of the growing Middle Eastern art market, with its desire to develop the art scene for commercial reasons.”

Mater is not alone. There are many other young, intelligent, grassroots artists coming from very different classes of Saudi society, with training in different fields. The strong presence of young female artists is a noticeable aspect of the scene. Even if very few international museums—the British Museum (thanks to its curator Venetia Porter), the Centre Pompidou and Lacma have been the most active so far—let many Saudi works and artists on to their turf, the Saudi art scene is one of the strongest emerging movements of the Middle East.

Young Saudi artists have been able to develop their work at a slower pace, showing primarily through private local initiatives, strongly rooted in Saudi civic society, such as the pioneering, highly professional, Athr gallery, directed by Maya el Khalil, and the 21.39 art festival organised by the Saudi Art Council, which is funded by private patrons only, both in Jeddah. In stark contrast with Misk, these long-standing initiatives have no geopolitical goal, but aim to discover, support and connect young Saudi artists, both locally and internationally.

Pioneer artists (including Ahmed Mater, Abdulnasser Gharem, Manal Al Dowayan and Ayman Yossri Daydban, as well as younger Saudi artists, both male and female) are all skilled networkers and are interested, above all, in exploring the communicative power of the image. Many use photography and mixed media, often centred on sociocultural and gender issues. There are the hilarious videos, not unlike sitcom comedies with a feminist touch, of Sarah Abu Abdallah or Awa Yahya Al Neami. Others are documenting and commenting on the vast “empty quarter” of the Kingdom—a term originally appropriated by Mater—or bringing the country’s illustrious cultural heritage into the present, as in the photographs of Moath Alofi, the textiles of Nojoud Alsudairi and the calligraphy of Abdul Aziz Al Rashidi. In the words of Venetia Porter, it is about “being rooted in one’s own history, but not bound by it”.

Some works can be remarkably rough, such as the in-your-face assemblages of pots and pans by Maha Malluh, and Zahrah Al-Ghamdi’s sculptures, which feel like organic webs or lumps. Other works are exceptionally refined, such as Dana Awartani’s geometric abstractions or Reem Al-Nasser’s weavings (produced by skilled Yemenis); sometimes they are both, as with Nasser Al Salem’s spatial experiments with calligraphy, and his installations close to Arte Povera. The very precise excursions into architecture and design crafted by Ahmed Angawi or Ayman Zedani are full of surprises, even for scholars of the built heritage.

Recently, some of these artists have begun exploring performative and sound works, as with the plays of Maisah Sobaihi or the DJ sets of Zahra Bundakji. I hope that the new creative hub-cum-community centre, Hayy (neighbourhood), which the private group Art Jameel and its director Antonia Carver are planning in Jeddah, will reinforce the present interdisciplinary current in the Saudi art scene.

I met these artists in the very early stages of their careers, and many of them have become truly independent creators, with a highly personal but formally rich oeuvre that reflects the rapid sociopolitical changes in the kingdom. Let us therefore hope the centralisation of art and culture now happening through the patronage of the Crown Prince and Misk does not trammel the energies, ambitions and achievements already set free by Saudi artists and private art initiatives.

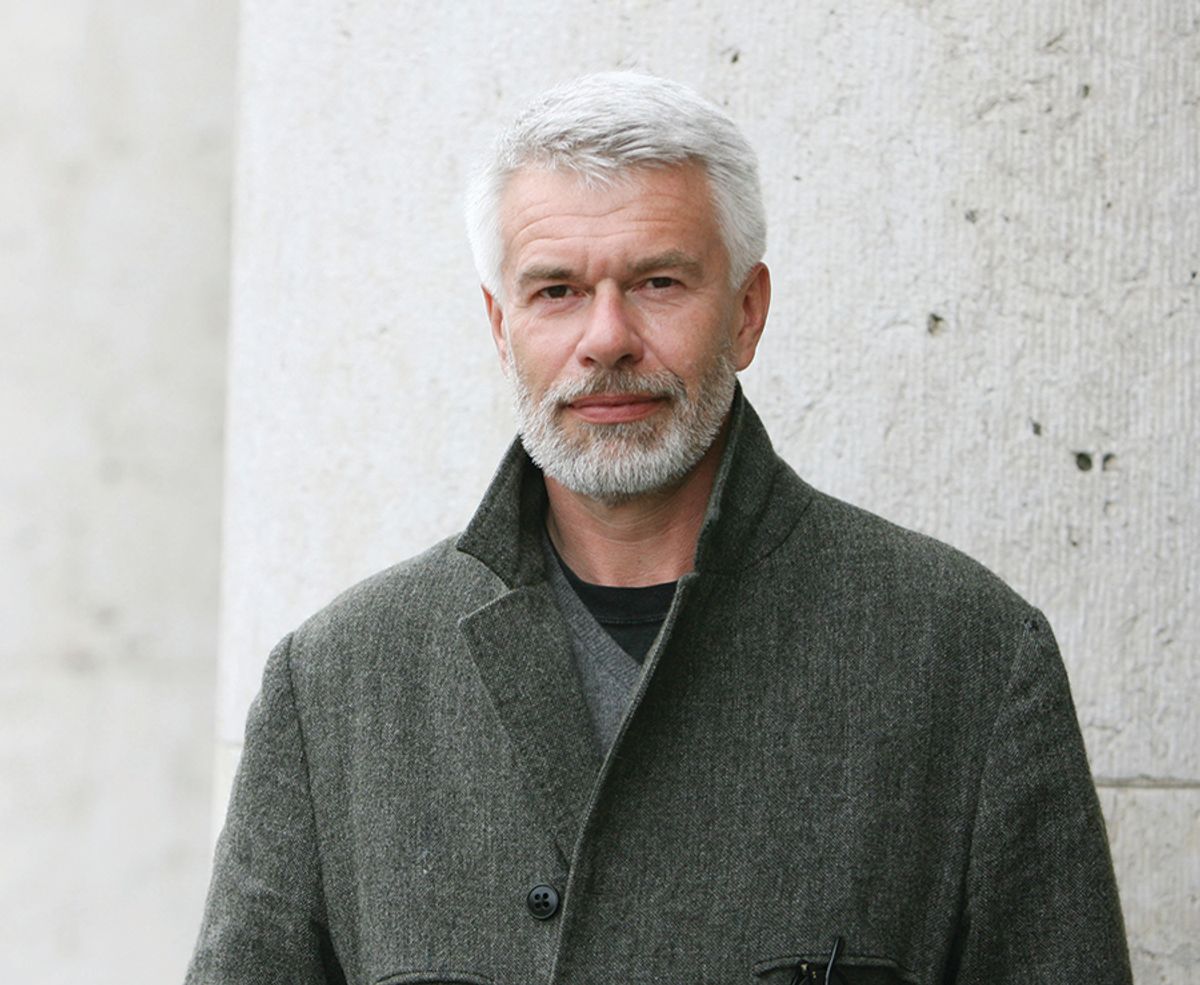

• Chris Dercon is the director of the Volksbühne Berlin and a former director of Tate Modern, London. He has been visiting Saudi Arabia regularly since 2011 and mentoring young artists. He has published several essays about Ahmed Mater, whom he met first in Abha in 2012