I must have missed the public acts of solidarity from Western galleries towards their Chinese peers in the wake of the cancellation of Art Basel in Hong Kong amid fears of the spread of coronavrius (Covid-19). There has probably been an outpouring of support from London and New York to the Hubei Fine Art Museum in Wuhan (disclosure: I curated a retrospective of Sean Scully there in 2016)—offers of financial and other assistance. I probably just missed them. Only a cynic could think that too many Western galleries too often see China primarily as a market.

Western museums are not always better. I was at the opening of the Centre Pompidou in Shanghai in November with a Chinese friend. “I have been to the Pompidou in Paris,” she told me. “They have not sent the best works here. It is all about money.”

“All” may be a bit strong, but the exhibitions were certainly free of iconic works from the collection.

Now, and for some time, things have been difficult in China’s art world ecology: the slowest rate of economic growth in 30 years, insurrections in Hong Kong, a trade war with the US—and now the virus shutdown. One mainland gallery friend, an Art Basel regular exhibitor, told me the fair would have been an uphill struggle, but at least it would have shown if art is capable of taking the measure of a convulsed and convulsing world. Another friend, also a gallery owner, called me to say that, while he was sorry Art Basel was cancelled—and that he would have been an exhibitor—the economy is so bad he had little expectation of sales.

Highs and lows

One of the intended consequences of President Xi Jinping’s anti-corruption drive is that there is less “loose” money looking for a home; one of the unintended consequences of Xi’s push to reinstate state-owned enterprises at the heart of the Chinese economy is a decline in the value of private enterprises and a flight of capital.

When the going gets tough, it is always useful to turn to the great Chinese thinker Lao Tzu, who said: “There is no high without low.” So, at a low time, what is the way back to high?

A couple of idle thoughts… Just over 20 years ago, when I staged Institute of Contemporary Arts events in China, I did so in shopping malls because there were, in effect, no galleries or museums of contemporary art. That has changed, but still only a sliver of China’s huge population is engaged with contemporary art, especially in the second- and third-tier cities. This is one reason the boom in museum building is so important (5,136 new museums in 2018). Its primary goal is, of course, economic—China needs to move from a manufacturing to a service and more creative economy—and requires a more creatively educated workforce to be successful. But it is also the case that you need first to experience art to want to engage with it. These new museums may provide invaluable art education and widen the circles for contemporary art.

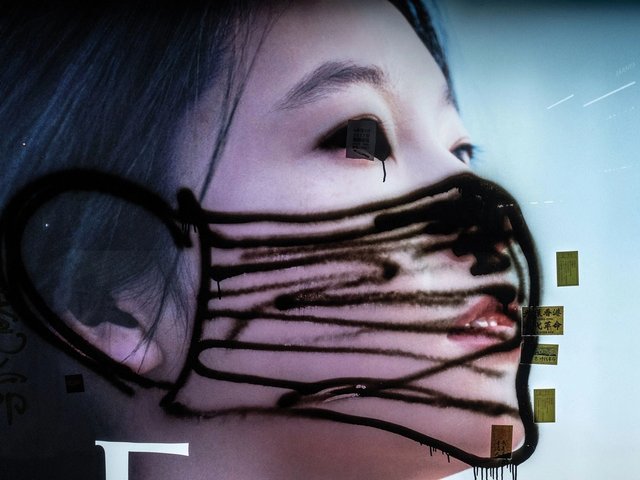

"The enormous Western art world dog may decide to turn its back on China—the country is so bloody complicated, and becoming more so—and set off, mask-free, to Basel in Switzerland."

Last November’s edition of Shanghai’s West Bund art fair concluded with a new initiative which was a real sign of the times: a global conference on art and education. Put some money, then, on art education in China as a route to wider engagement.

A second thought… China is moving south. Shanghai and Beijing still attract the most foreigners, but it looks to me that Guangdong in the south of China, and especially Shenzhen, will be at the heart of China’s new economy—and of its new art economy. Shenzhen is slated to be China’s Silicon Valley. Huawei and Tencent (which developed WeChat) are already there, as are AI companies and architects from Renzo Piano, Rem Koolhaas and Norman Foster. The Victoria & Albert Museum arrived five years ago (disclosure: I brokered the initial deal) and now a large number of new design and art museums are plotted to open.

Age of opportunity

The average age in China may be 37.1, but in Shenzhen, a city of 11 million, the average age is 32-33. These tech professionals—looking for cultural experiences in a city that can’t yet provide them—are ripe to engage with art, and even collect it.

Now, I have a very small dog in this fight, having spent the past 16 years flying between London and China. But the enormous Western art world dog may decide to turn its back on China—the country is so bloody complicated, and becoming more so—and set off, mask-free, to Basel in Switzerland.

Or it could remember its beleaguered art colleagues in China. Hold an auction, invite Chinese galleries (when the masks are off) to take up residence in Western capitals temporarily; work with the new museums in second- and third-tier cities on art education, as well as other projects (at cost). Or it could even stage a series of exhibitions across Europe called How China has Influenced Art in Europe in the 20th Century. And then offer it to the Hubei Fine Art Museum in Wuhan.

• Philip Dodd will curate an exhibition of Hsiao Chin at the Mark Rothko Art Centre, Latvia, in April and museum exhibitions in China of Eduardo Paolozzi. He is the chairman of Made in China (UK)

• Read all of our coronavirus coverage here.