In the first days of the arrival of the “migrant caravan”, as President Trump described those travelling from politically unstable regions in Central America to seek asylum in the US, the news was filled with horrifying photos of women and children being gassed by US soldiers along the Mexican border. So it came as a shock when the art blog Hyperallergic published an article detailing how the tear gas canisters being used in these military actions were manufactured by a company owned by Warren Kanders, the vice chair of the board of trustees at the Whitney Museum and a significant sponsor of the museum’s current Warhol retrospective.

The fact that Trump’s weapon of choice against those legally seeking refuge in the US could so directly be tied to the Whitney Museum generated an outcry. Social media rumblings turned into a wave of amorphous online protest. To the frustration of many, Adam Weinberg, the museum’s director, did not respond immediately, per the policy of the museum not to comment on the personal dealings of their board members.

It was the Whitney’s own staff members who managed to break through this wall of silence. In a letter to their boss, which was leaked to Hyperallergic, they pointed out the contradiction between the museum’s stated goals and its leadership: “So many of us are working towards a more equitable and inclusive institution… We cannot claim to serve these communities while accepting funding from individuals whose actions are at odds with that mission. This work which we are so proud of does not wash away these connections.”

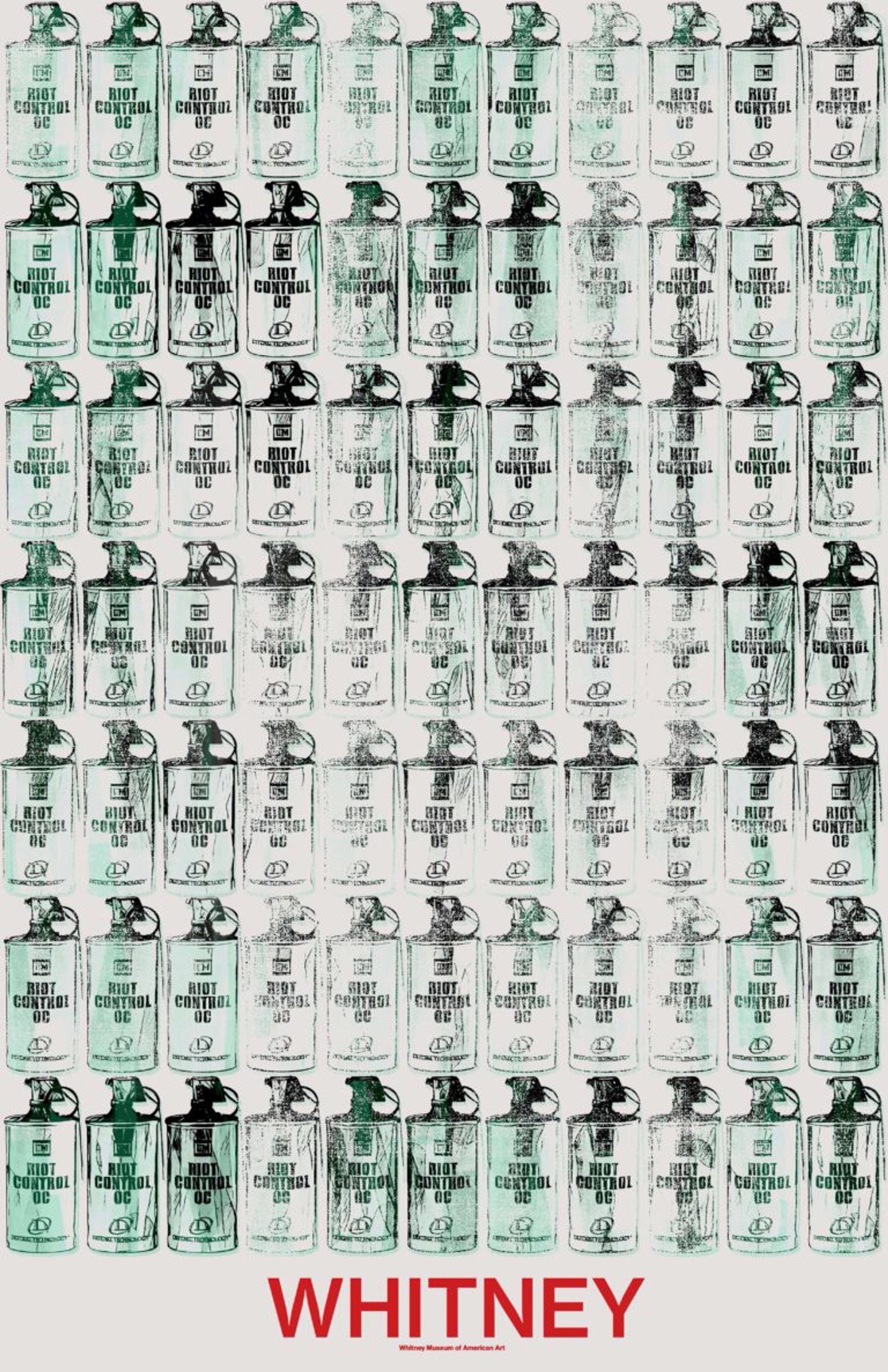

A poster by the group Decolonize This Place protesting the Whitney's connection with Warren Kanders, the vice chair of the board of trustees of the Whitney and a significant sponsor of the museum’s current Warhol retrospective, who owns the tear gas manufacturing company Safariland Decolonize This Place

Weinberg’s response to his staff, also sent to the press, was replete with the language of empathy. “We at the Whitney have created a culture that is unique and vibrant—but also precious and fragile,” he wrote. “This ‘space’ is not one I determine as director but something that we fashion by mutual consent and shared commitment on all levels and in many ways.” But this delicacy of language was at odds with the substance of the missive, which took a hard line when it came to the board, invoking a subtly law-and-order position: “Even as we contend with often profound contradictions within our culture, we must live within the laws of society and observe the ‘rules’ of our Museum.”

At the heart of Weinberg’s letter was a claim that raised eyebrows: “We each have our critical and complementary roles: trustees do not hire staff, select exhibitions, organize programs or make acquisitions, and staff does not appoint or remove board members.” Only in the most narrow and literal sense could this possibly be true. The fact is, for US museums, which depend inordinately on the money that comes from board members and other private donors, people like Kanders wield tremendous influence on all aspects of the museum’s operation. Board members are not simply ATMs; they expect to steer the institution in ways that are sometimes, if not entirely, at odds with the expert curators, educators and other staff members who make up the institution.

None of this is new, nor is Kanders unique. As the artist Hans Haacke made a career of pointing out, museum boards are hotbeds of conflicts of interest, bad politics and money laundering. In works like MoMA Poll (1970), which asked museum visitors their opinion on the then New York Governor (and MoMA board member) Nelson Rockefeller’s position on the Vietnam War, thus subtly tying the museum to his hawkish rhetoric, and Shapolsky, et al. Manhattan Real Estate Holdings, a Real Estate Holdings, a Real-Time Social System, as of May 1 1971 (1971), which traced in intricate detail the operations of a notorious slum lord who seemed to have personal and financial connections to the Guggenheim’s board, Haacke pointed out the long-standing imbrication of museums in the worst aspects of capitalist exploitation via their board members.

Singling out Kanders will not solve the larger problems museums face in reconciling their stated missions and their trustees’ business practices. If Kanders is removed from his role at the Whitney, he will mostly be replaced with someone else whose dealings are equally uncomfortable. But neither is the exercise useless or unimportant. The protest against this one board member may well weaken the ability of museums to withstand future critiques, especially if, as I suspect will be the case, we see an uptick in such protests.

Weinberg acknowledged the shift in political mood when he wrote in his letter that societal ills “have understandably led to tremendous sadness and frustration, quick tempers, magnified rhetoric and generational conflict”—a propensity to complain, in other words. What his letter does not reflect, unfortunately, is a recognition that in such a climate, the same old arguments in favour of ignoring the business dealings of museum trustees, of pretending museum programming can function independently of those funding it, cannot stand for long. No one is buying any more the idea that the museum can hold itself at arm’s length from the filthy lucre on which it depends.

• Aruna D’Souza is the author of Whitewalling: Art, Race and Protest in 3 Acts