It was obviously already a done deal. On 9 April, the hearing of the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors turned into an ashes-in-your mouth formality for opponents of the proposal to replace four buildings at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (Lacma) with a structure that some consider highly suspect. Despite a last-minute storm of controversy that exposed a disturbing stream of damaging facts, such as a one-and-a-half-mile reduction in linear wall space in the galleries, the County Board of Supervisors unanimously voted yes on the project. Even before the floor was open to public comments, three of the five supervisors revealed, in casual banter, that they would be approving the $650m project.

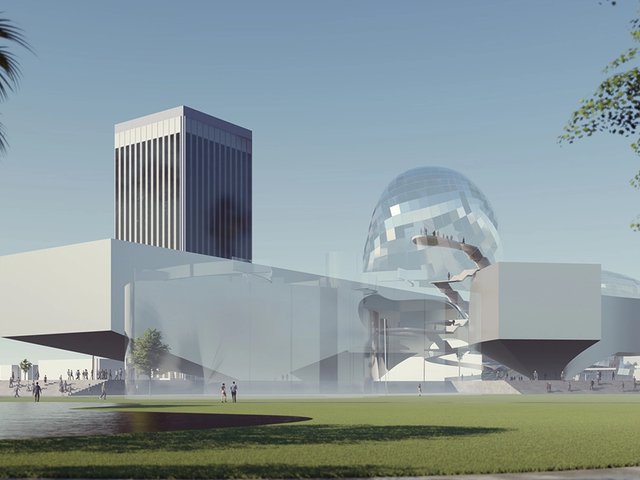

For the past decade, Lacma’s director Michael Govan has been working with the Swiss architect Peter Zumthor on a building to replace the museum’s original three 1960s structures by William Pereira, and a fourth by Norman Pfeiffer, opened in 1986. Zumthor’s proposal for an elevated, concrete structure floating over Wilshire Boulevard has been controversial for many reasons, most conspicuously because it drops what looks like a freeway overpass above the city’s most ceremonial street.

But this is Govan’s do-or-die pet project, and he has promoted the design with considerable charm. Going into the hearing, it seemed he had orchestrated a score of advocates to add their voices to a choir singing non-stop praises, including the actors Brad Pitt and Diane Keaton. Meanwhile, the author Victoria Dailey, among the half-dozen opponents who spoke, made the alarming point that no floor plan of the gallery spaces has been made public, so no one, including the county supervisors, can make an informed decision.

But the supervisor Sheila Kuehl snapped the meeting closed after two hours when she declared she needed no more information to vote yes on the final environmental impact report (FEIR), released in March. The vote triggers the release of the remaining $117.5m of the county’s $125m construction grant and a $300m bond, sums that probably guarantee it will go ahead.

Lacma had conducted its design and planning process largely in secret, with scant public input. The supervisors’ approval has now provoked public opposition at a time when damaging facts emerging in the press have signalled the scheme’s destructiveness—not only to the community but also to the museum itself. (For instance, half of the covered outdoor space has been counted as “gallery space” on the pretext that it shows sculpture.)

Within two days of the vote, the Miracle Mile Residential Association resolved to sue both the County Board for approving the FEIR, and the City of Los Angeles. The press release announcing the lawsuit stated that the FEIR was “rife with inaccuracies and inadequate information” and gave incorrect numbers, such as the drop in overall square footage—37%, not 10% as listed. It also analysed alternatives to the Zumthor scheme that falsely put the project in a favourable light, and neglected to mention less impactful schemes, such as joining the four extant buildings to create a doughnut-like structure around a courtyard. Most glaringly, it neglected to point out that there is enough land to fit a version of the Zumthor scheme with the same square footage without bridging Wilshire and wasting that site for future development.

“Neither Lacma nor the County Supervisors have honestly addressed our concerns,” the lawsuit press release says. “They have taken a ‘damn the torpedoes, full speed ahead’ approach.”

The press release also identifies a parking structure to be built on Ogden, a nearby residential street, as a condition of the Zumthor theme. But the building exceeds legal height limits. Ironically, the last stand to save Wilshire Boulevard from the unwanted bridge may be fought on Ogden, not Wilshire.

Although operated by a private non-profit, Museum Associates, Lacma is run as a public trust. Members of the public have had to sue to have their opinions heard after a process conducted by a few people behind closed doors. The supervisors’ meeting was short, but the lawsuit promises to be long.

Joseph Giovannini is an architecture critic and teacher