“She doesn’t answer the phone, does she? I hope she doesn’t start picking up bids with clients.”

It was 2015. The new Phillips’ chairman for UK and Europe was on his inspection tour of the Paris office where I worked as an intern in the contemporary art department. His comments struck me as odd. What bothered him so that I could be the first point of contact for a client? His anxiety at my mere presence seemed irrational. I did not get a chance to underline the fact that I had already worked the saleroom for several auctions at Sotheby’s the previous year.

It is difficult to talk about prejudice in an industry that spares no one. One may escape classism by having the right degree, only to be hindered by nepotism. And a notable family background will not protect one from sexism. Even those who tick all the right boxes struggle under the weight of office politics and financial targets—as one high-flying specialist once said: “I sell, therefore I exist.” Despite the rewards of working collectively around history-making works of art, the pressure at all levels is immense.

Discrimination in such a context tends to be subtle in its manifestations, easily dismissed as misjudged or irrelevant. The cosmopolitan nature of the art world makes it even more elusive: people travel extensively, have ties to and collect from various cultural backgrounds. Many companies have departments dedicated to Asian, African or Middle Eastern arts, past and present. And yet, a hierarchy is always there. It is evident when one looks at auction house specialist directories, present when it comes to salary raises and promotions. It is in the words “niche” and “emerging”, and may impact your freedom to lunch at the Fondation Beyeler restaurant. Diversity and inclusion groups don’t do much to change a persistent feeling that a certain category of people are not a “good match” for the image of a major auction house or gallery. Or at least, not at a certain level.

Angela Davis points to the very problem of the word inclusion. To quote Elaine Welteroth: “By centring and positioning whiteness as superior, whiteness as the norm, and everything else as a deviation, a racial hierarchy is reinforced.” Side-by-side, but not on an equal footing: recent comments about double standards in restitution issues are precisely about that hierarchy. As early as the 1960s in the institutional world, a curator like Kynaston McShine was able to organise era-defining exhibitions such as Primary Forms at the Jewish Museum in 1966, or Information at MoMA in 1970, a landmark in the scholarship around conceptual art. A list of 47 black curators promoted in 2019, compiled by the website Culture Type, shows that black expertise in art is undeniably present and does not concern the presentation of black artists exclusively.

Yet cases such as Chaedria LaBouvier’s experience at the Guggenheim show that much still needs to be done. In the wake of Black Lives Matter, these imbalances need to be addressed decisively if we are ever going to move beyond symbolic donations and performative posts of support on social media.

The subject is even more complex when we look at the art market, prompting one to wonder whether it can be reformed at all. Can the market be an ally? I believe the market makes art history in the same way that scholars do. Value does serve as an incentive for preserving an artist’s work, and this is why we must urgently re-evaluate what we consider valuable, who appraises that value, and redefine the very term. It is also a conservation issue. Who will be the Old Masters of 400 years’ time? Chances are, they may not look like Rembrandt.

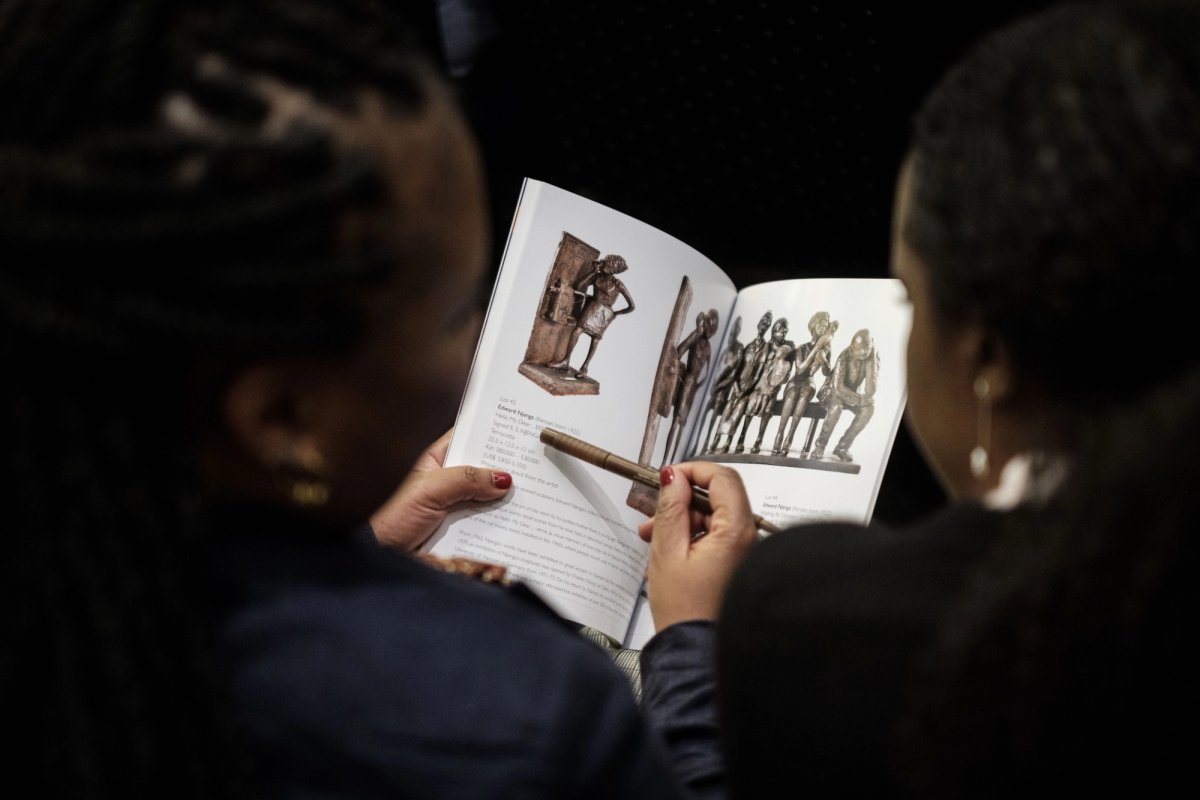

Only by involving people from all backgrounds, at every level, can we, as an industry, attain a richer and more meaningful view of art history and impact the value system of future generations. The art market is making some efforts to adapt, with a few meaningful appointments and the rise of independent gallerists such as Didier Claes and Mariane Ibrahim, plus the creation of fairs such as Touria El-Glaoui’s 1-54. Editors like Anna-Alix Koffi and Amy Sall are updating the discourse, while groups at Christie’s are reading Robin DiAngelo’s book White Fragility, along with several other initiatives. But we need to do more.

Paying lip service, however educated, while continuing to apply the same obsolete models and mindset will not address the changes that need to be made. Adapting does not mean simple attempts to appeal to a younger generation of collectors with eye-catching names and attractive estimates. It may mean the advent of another model altogether, based on the changing values of an entire generation of opinionated troublemakers who are in the streets calling for equality and more actions to protect the environment. Institutions are starting to take notice of the deeper changes this implies, in great part thanks to staff and various collectives voicing their concerns. Will the market follow?