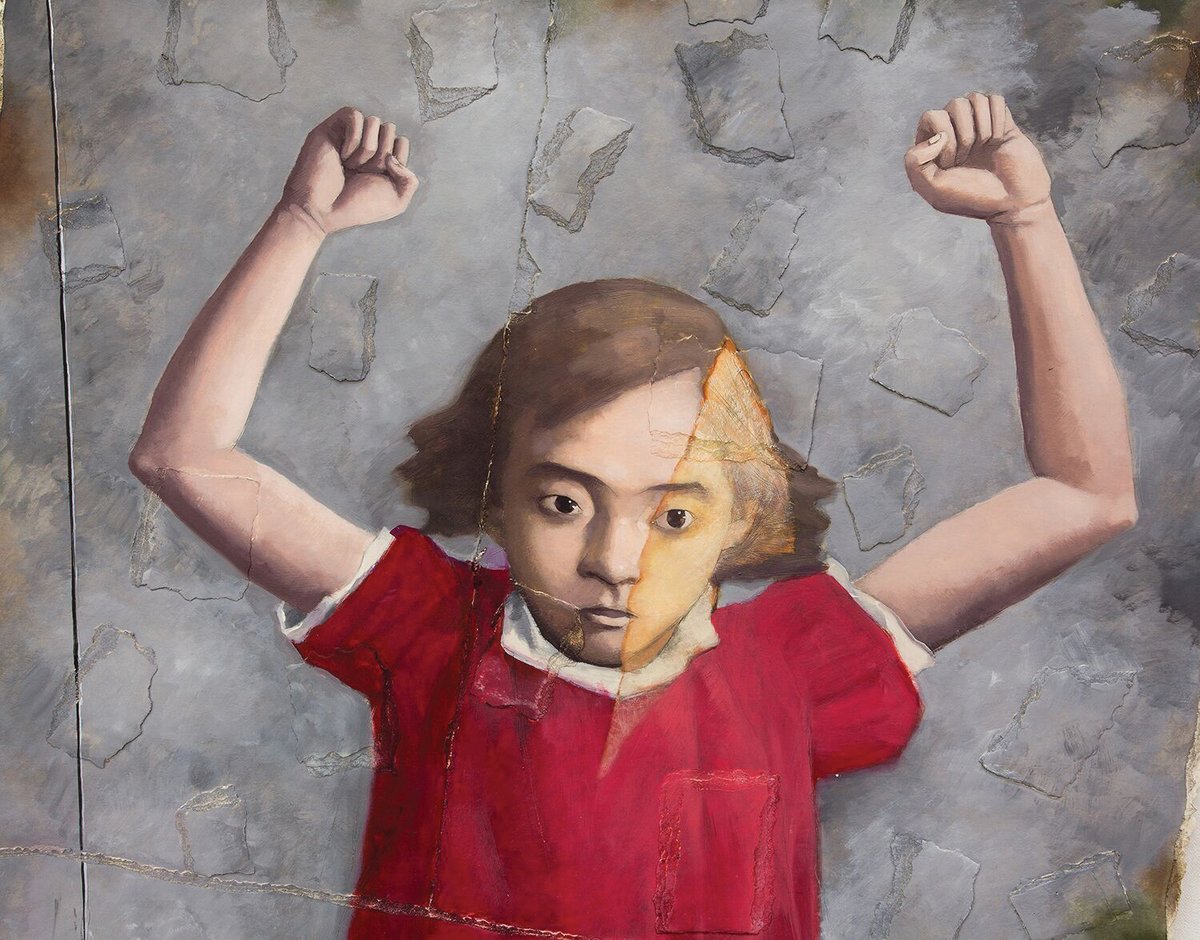

When I visited Zhang Xiaogang in his Beijing studio in the spring of 2016, I entered with a mixture of derision and respect. Of course, I could have nothing but admiration for this artist who had bridged the cultural divide between China and the rest of the world in the 1990s with his famous Bloodline series. At the same time, I was suspicious of his choice of subject matter—solemn portraits of nuclear families often dressed in Communist garb—as if playing the Chinese card was a calculated strategy aimed at attracting attention from Western viewers looking for something distinctly “Chinese-y” for their collections.

But as I sat with this gentle and sensitive artist, his explanations showed me that nothing could be further from the truth. As Zhang explained, he was exploring his own identity in search of a unique voice to insert into the global cultural dialogue when he found inspiration in a collection of old photographs hidden away in his parents’ home. It was just a lucky coincidence that his exploration of this material coincided with the arrival of Western curators and collectors eager to find “Chinese-ness” in Chinese contemporary art.

I was struck during this encounter by the vast difference between Zhang's personal experience and that of the younger generation of artists that I had been studying since 2012. Mostly born in the 1980s and 1990s, these young Chinese artists had never experienced the Mao era, growing up instead with the open-door policy and a vast influx of Western brands and influences. Their photo albums were filled with visits to Disneyland and family trips to London and New York. Some were educated abroad, but even those who remained in China were thoroughly familiar with global contemporary art, being astute surfers of the internet. China’s “Great Firewall”, barring use of Twitter, Facebook and Google, didn’t stop them. They downloaded VPNs and various apps that let them circumvent the censors.

Viewing their artworks, I learned to stop looking for a “Chinese identity” and instead developed the notion of what I like to call a “post-passport identity”. For example, the abstract painter Qiu Xiaofei and the science fiction animator Lu Yang compare their practice to that of a DJ, sampling from various cultures and free to move beyond Chinese iconography. Lu Yang said to me, “I don’t have a nationality—I live on the internet” and it is indeed through online interactions with other netizens, scientists, filmmakers and composers that she creates her videos and interactive installations. Despite government policies reinforcing nationalism in China’s youth and educational agendas warning of dilution of Chinese values, these individuals emerged as thoroughly global citizens, unwilling to live within the boundaries of geography or politics.

I interviewed well over 100 young artists over the course of five years and consistently they insisted on relinquishing the label “Chinese artist”. Still, I found something very Chinese in their insistence that they were “global artists”. Because, in point of fact, China was at the centre of globalisation, and these young adults were impacted directly by economic upheavals that can barely be imagined in the West. They have experienced their country changing from an agrarian society to a land of mega-cities, and even within those cities the neighbourhoods of their childhoods have been redeveloped beyond recognition.

As globalisation hit home, family traditions were supplanted by bootleg DVDs and Starbucks coffee. To embrace a “post-passport identity” was not a capitulation to the West, but an embrace of a transformation that occurred specifically in China.

Looking at Chinese contemporary art today—the art made by this generation of millennials—you will not find pictures of Mao or references to imperial dynasties. Instead, there are multiple strategies at play addressing the impact of globalisation on these young lives. A cursory glance might lead one to think that these artworks are no longer authentically Chinese, having lost the “local” for a more homogenised global vocabulary. But that would be a mistake. These artworks intentionally challenge stereotypes and presumptions, translations and mistranslations, in order to revise expectations of artists from mainland China. It is my prediction that this new kind of Chinese contemporary art will open doors for these artists and offer them new opportunities for artistic freedom. More importantly, it will open the eyes of Western viewers and hold a mirror up to our antiquated notions of Chinese art with examples of some of the most exciting works of art being made anywhere in the world today.

Barbara Pollack is the author of Brand New Art from China: A Generation on the Rise (IB Taurus). Zhang Xiaogang: Recent Works is on view at Pace Gallery in New York through 20 October.