Evidence that Marcel Duchamp may have stolen his most famous work, Fountain, from a woman poet has been in the public domain for many years. But the art world as a whole—museums, academia and the market—has persistently refused to acknowledge this fact. The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York is the latest eminent body to bury its head in the sand. It has just published a new edition of Calvin Tomkins’s 1996 life of Duchamp, updated by its author. Ann Temkin, MoMA’s chief curator of painting and sculpture, praises Tomkins in her introduction for his “thorough research”. But Tomkins avoids addressing the implications of the question marks over the origins of the work that Duchamp himself raised in 1917.

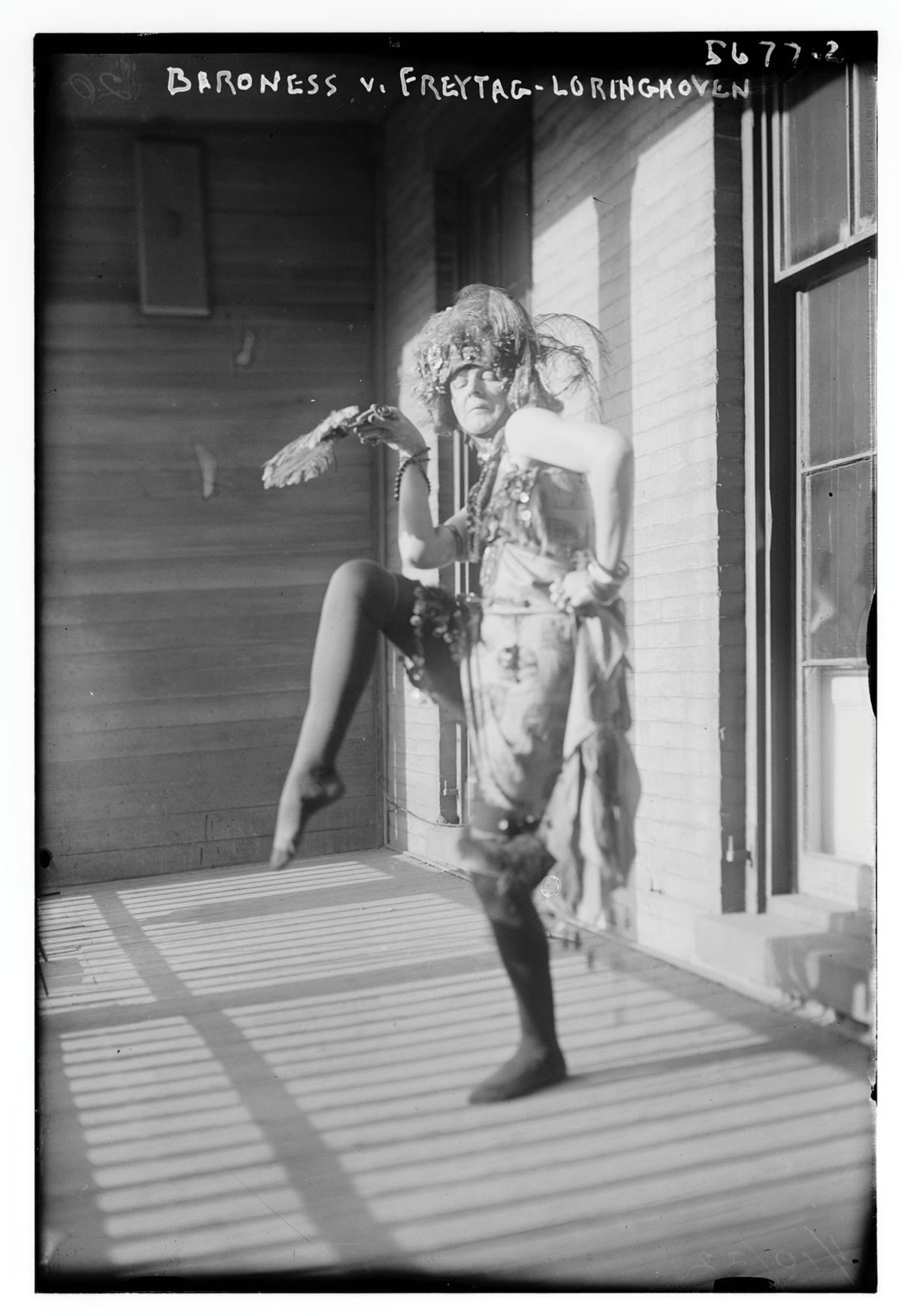

The public has a right to believe what it reads on a museum label. The Moderna Museet, Stockholm, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, Tate Modern, the National Gallery of Canada, the National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto, Indiana University Art Museum, Bloomington, the Centre Pompidou, Paris and the Israel Museum should all re-label their copies of Fountain as “a replica, appropriated by Marcel Duchamp (1887-1968), of an original by Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven (1874-1927)”.

The extraordinary fact that has emerged from the painstaking studies of William Camfield, Kirk Varnedoe and Hector Obalk is that Duchamp could not have done what he said he did late in life. Irene Gammel and Glyn Thompson have revealed the truth of his much earlier private account that he did not submit the urinal to the Society of Independent Artists exhibition in New York in 1917. Nevertheless, Duchamp’s late, fictional story is still taught in every class and recited in every book.

Duchamp maintained that he bought the urinal from the J. L. Mott Iron Works in New York, signed it with the pseudonym R. Mutt, and submitted it to the Independents exhibition, calling it Fountain. The urinal was rejected despite the objection of Duchamp’s rich friend Walter Arensberg, who argued that the society must honour its own rule and hang everything submitted. The urinal was a work of art, he claimed, because an artist had chosen it.

The submission and rejection of Duchamp’s urinal is now regarded as one of the early turning points in the history of Modern art. Fountain is always cited as the source of conceptualism, the Modern art movement that America, rather than Europe, gave the world.

In conceptual art, the idea behind the work is more important than its visual appearance or any aesthetic considerations. Mere choice is enough to transpose any object into a work of art. The problem is that this new orthodoxy is based upon a myth, and this myth is not nearly as old as it claims.

Scholars have long since proved that Duchamp could not have bought the urinal from the J. L. Mott Iron Works because Mott didn’t sell that particular model. Most tellingly, on 11 April 1917, just two days after the board had rejected it, Duchamp wrote to his sister, a nurse in war-torn Paris, telling her that “one of my female friends under a masculine pseudonym, Richard Mutt, sent in a porcelain urinal as a sculpture”. The explosive contents of this letter did not enter the public domain until 1983 when the missive was published in the Archives of American Art Journal.

The mere fact that Duchamp referred to the urinal as a sculpture suggests that it could not have been his, since by 1913, prompted by the work of the wealthy, chess-playing writer Raymond Roussel, he had stopped creating art. His Roussel-inspired “Readymades” were elaborate, personal rebuses to be read, not viewed.

The literary historian Irene Gammel was the first to discover who Duchamp’s “female friend” was. She was born Else Plötz in Germany in 1874, the daughter of a builder and local politician who philandered freely and beat her mother. Afflicted with syphilis, her mother attempted suicide and died later in an institution. As Elsa put it, she “left me her heritage… to fight”.

Elsa first married the leading Jugendstil architect August Endell, then Felix Paul Greve, the translator of Oscar Wilde, who faked his own suicide to escape his creditors and fled with Elsa to America. Her third marriage was to Leopold Karl Friedrich Baron von Freytag-Loringhoven, the impoverished son of a German aristocrat who had also escaped to America to avoid debts. He soon vanished with Elsa’s paltry savings but left her with a title and entrée into artistic circles in New York.

Elsa simultaneously inspired and repelled all who came into contact with her, from Ezra Pound to Ernest Hemingway. Nevertheless The Little Review treated her as a star and published her poems alongside excerpts from James Joyce’s Ulysses.

Elsa’s genius was to find new ways to break out of the social straightjacket that bound women so that she could fight her mother’s battle in public, whenever and wherever she wanted, not when men told her she could.

In October 1917, the painter George Biddle described her room in New York filled with “odd bits of ironware, automobile tiles… ash cans, every conceivable horror, which to her tortured yet highly sensitive perception, became objects of formal beauty… it had to me quite as much authenticity as, for instance, Brancusi’s studio in Paris.”

Elsa was a poet of found objects, but she didn’t leave them as they were—she transformed them into works of art.

Elsa exploded in fury when the US declared war on her motherland, on Good Friday, 6 April 1917. Her target was the Society of Independent Artists, whose representatives had consistently cold-shouldered her. We believe she submitted an upside-down urinal, signed R. Mutt in a script similar to the one she sometimes used for her poems.

Armut—the homophone of R. Mutt—has many resonances in German. It is used in common phrases to mean “poverty”, and in some contexts “intellectual poverty”. Elsa’s submission was a double-pronged attack. The society was hoisted by its own petard, for in accepting the entry it would demonstrate its inability to distinguish a work of art from an everyday object, but in rejecting it, it would break its own rule that the definition of what was art should be left to the submitting artist. Hence the “intellectual poverty” of its stance.

The urinal was Elsa’s declaration of war against a man’s war—an extraordinary visual assault on all that men stood for. As a sculpture of a transformed everyday object, it deserves to rank alongside Picasso’s Bull’s Head, 1942, made of bicycle handlebars and a saddle, and Dali’s Lobster Telephone, 1936.

If Duchamp did not submit the urinal, why would he pretend later that he did? After Elsa died in 1927, forgotten and in abject poverty, Duchamp began to let his name be associated with the urinal, and by 1950, four years after the death of Alfred Stieglitz, who photographed the original Fountain, he began to assume its authorship.

After he reluctantly abandoned his ambition to become a professional chess champion in 1933, Duchamp started to rebuild his artistic career by repackaging his early work. The problem was that there was not much of it. Only one of his original Readymades still existed, forgotten, in a drawer in Walter Arensberg’s desk. It is from this period, beginning in 1936, that replicas of the “lost” Readymades began to appear. Elsa’s urinal plugged a hole, but to make it his own Duchamp turned it into an attack on art itself.

Duchamp had long hated art. Both his elder brothers had become successful artists; he had not. Envy seeps out of many of his unguarded utterances: “Why should artists’ egos be allowed to overflow and poison the atmosphere?” he said in 1963. “Can’t you just smell the stench in the air?”

When the mood took him, Duchamp could be honest about his dishonesty. In an interview in 1962, he told William Seitz: “I insist every word I am telling you now is stupid and wrong.” Why, then, has the art world persisted in believing an account grounded in the myths he promulgated?

The reason is simple: too much has been invested in Duchamp’s fiction. Countless artistic, curatorial and academic theories have been based upon it. And national pride is at stake, for conceptual art was America’s contribution to Modernism, supposedly dating from 1917, not the 1960s when Duchamp’s work began to weave its spell.

Added to that is the money. Millions of pounds have been invested not just in the 17 or so copies Duchamp authorised of Elsa’s urinal, but in the oceans of conceptual art legitimised by his anti-aesthetic. And in the wake of these ideas, expensive studio equipment and lengthy craft training have been swept out of education because it’s cheaper to think than make.

Duchamp’s mean and meaningless urinal has acted as a canker in the heart of visual creativity. Elsa’s puts visual insight back on to the throne of art.

• A longer version of this article will appear online at www.scottishreviewofbooks.org