With the Covid-19 pandemic raging, and Britain, like so many other countries, in lockdown until further notice, ground-breaking contemporary art movements and exhibitions feel like a distant dream. But the ravages of the virus are only the latest of a whole set of challenges that now face young British artists, following radical reforms to the UK’s arts education and social security systems. It is a very different cultural landscape from that which faced Charles Saatchi’s YBA Wunderkinder nearly a quarter of a century ago.

The glory days

The stench. That was the thing that first hit visitors back then as they walked into Sensation, the exhibition at the Royal Academy of Arts (RA) in 1997 that introduced a wider public to the shockingly new kind of art that young British artists were producing —and Charles Saatchi was collecting. Five months earlier, a new Labour government had been elected with a massive majority, beginning a fresh era of party-political hegemony, during which Britannia actually became quite cool.

Works like Damien Hirst’s A Thousand Years, with its stinking fly-blown cow’s head, Marcus Harvey’s monumental painting of the murderer Myra Hindley made with children’s hand prints, and Tracey Emin’s tent embroidered with the names of everyone she had slept with, all, in their own vibrantly different ways, stuck two fingers up at Britain’s stuffy cultural establishment and said something about the times the artists were living in.

“There was a certain kind of iconoclasm,” recalls Gavin Turk, whose mock English Heritage plaque commemorating the two years he had worked as a postgraduate at the RA was included in Sensation. The selection was co-curated by Norman Rosenthal, then the RA’s exhibitions secretary.

“There were a lot of new possibilities. Everyone thought there were certain subjects and topics that hadn’t been addressed,” adds Turk, whose postgraduate submission questioning the cult of fame was denied a certificate by the Royal College of Art (RCA). “It had a kind of political shell that was different from the soft aesthetic consideration of art of the previous generation.”

Meanwhile, Turk, Hirst, Emin et al have become mature British artists. The lockdown resulting from coronavirus has prompted some mellow responses from them. Hirst meditated illuminatingly on his extraordinary career during a four-day studio Q&A on Instagram, and Turk invited visitors to a virtual Easter hunt for “Cosmic Eggs” in his studio via the Zoom video conferencing platform. Charles Saatchi’s gallery has been hosting a blockbuster Tutankhamun show, organised by the Los Angeles-based IMG entertainment group, now closed because of the virus. And another government is newly installed in Westminster with a big majority, but this time of a populist Conservative stripe, and it, as well as everyone else, is having to grapple with the disastrous effects of the coronavirus crisis.

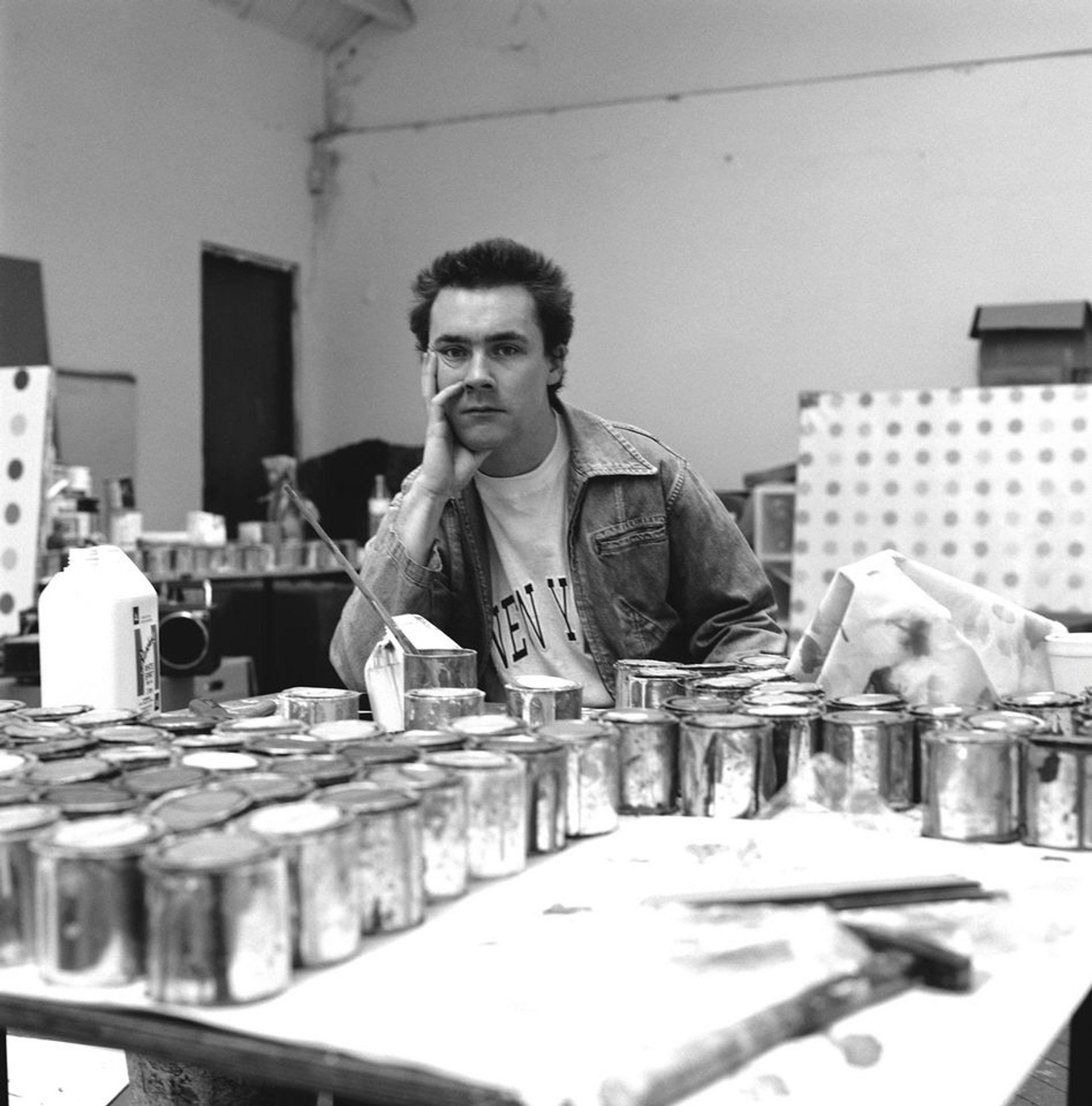

Original YBAs such as Damien Hirst were able to study for free at prestigious London art schools, which are now increasingly gentrified and facing protests © Johnnie Shand Kydd. All Rights Reserved, DACS/Artimage 2020

When the horror of the pandemic does eventually subside and life returns to some semblance of normality, how will Britain’s artists respond to the crisis and the way it has been handled? Will they focus on the stark divisions it has exposed between “outsiders” and “insiders”, the privileged and the poor, the mega-rich and the key workers? Will there be a youthful resurgence of creativity and iconoclasm, just as there was when Saatchi was so actively acquiring and promoting the work of the YBAs?

No such thing as a free education

If there is to be any chance of this happening, the artists involved will have to overcome more obstacles than were around in the mid-1990s. And we are not just talking about the prospect of an unprecedented economic recession. Several of the most original and audacious artists in Sensation, such as Hirst and Emin, came from modest backgrounds. At the time, they were able to study for free on government grants at prestigious London art schools like Goldsmiths and the RCA.

In 1998, the Labour government controversially introduced tuition fees. Under the Coalition Government, these have now increased to more than £9,000 per annum for undergraduates, plus loans to cover living expenses. Yet student numbers have never been higher. Official government data indicates there were a record 2.4 million students at UK higher education institutions in 2018-19.

“We’ve seen a massive expansion in the number of people going to university. Dissecting the data is really tricky,” says Dave O’Brien, a research fellow at Edinburgh University and co-author of the 2018 study, Panic! Social Class, Taste and Inequalities in the Creative Industries. O’Brien says there is no detailed data available on the socioeconomic background of art students. Anecdotal evidence, however, suggests the prospect of a seven-figure burden of debt has been deterring the disadvantaged.

“There’s been class-cleansing,” says Kevin Biderman, a tutor in critical and historical studies at the RCA, who was among more than 100 staff and students picketing the RCA’s Battersea campus on 10 March as part of a national strike by lecturers at UK universities over a range of grievances, including increased workloads and the casualisation of teaching. Ten days later, the college closed in response to the pandemic. Like many colleagues, Biderman is now teaching online via Zoom and has yet to receive assurances that he will still be employed by the RCA after May. Biderman says that, on average, his tutorials of 32 postgraduate students contained just “one or two” from a British working class background. Around 20 are higher-paying international students. “You have a situation where it is a finishing school. Art education is something for an elite,” Biderman adds. “When you do get working class students, they’re having to do five different jobs.”

Students on zero-hours contracts being taught by teachers on zero-hours contracts have become a distinctive feature of Britain’s marketised further education system. In London, this culture of bottom-line managerialism has left the finances of art colleges increasingly dependent on well-off foreign students. International postgraduates at the RCA are charged £29,000 per annum, more than double the £9,750 charged to home students. How this model can survive in the wake of a pandemic, which has made studying abroad a potentially life-threatening experience, is any vice chancellor’s guess.

The impact of gentrification

“Something has gone wrong, big-time,” says Tim Stoner, a London-based painter from a working class Essex background, who was a contemporary of the Sensation star Chris Ofili at the RCA in the early 1990s. Stoner has lectured at the RCA, Goldsmiths, Chelsea and the Slade, and has become increasingly concerned about the gentrification of Britain’s art colleges. “What worries me now, particularly with the removal of a certain class of student from a lot of art schools, is we’re going to end up with a very myopic culture,” says Stoner. “I would not have gone to art school if I were 19 years old now. I could not have imagined walking into that level of debt.”

Stoner says a “very assertive idea of art as a career” has been one of the most pervasive legacies of the YBAs, who, like him, grew up under Margaret Thatcher. “It kind of worked, it was needed. But now I have students who want to know how to get a gallery,” Stoner adds. “The mature students, some of them with a bit of money, can afford to navigate their way into art education. Younger, poorer working class students can’t afford to do this.”

The Conservative government, keen to promote what it views as more economically beneficial STEM-based education, publishes data that exposes art as a “low-value” subject. According to research published in February by the Institute of Fiscal Studies (IFS), commissioned by the Department for Education, creative arts are the worst investment of all degrees. Lifetime returns for creative arts graduates are “close to zero” for women, and “negative” for men, according to the IFS report. These attitudes may well harden within the Treasury once it is faced with the colossal bill for its economic rescue packages.

But, as O’Brien, who researches inequality in the creative industries, points out, there will always be people who want to make art. “The question is, what are the barriers preventing them from turning their creativity into careers?” he asks. “Expense is crucial. The telling difference isn’t the university system, it’s the social security system.” He describes the government’s Universal Credit benefits scheme introduced in 2013 as “punitive”.

A lack of affordable accommodation and studio space are further barriers. Yet young Britons from less well-off backgrounds are still trying to make careers as artists in gentrified 21st-century London.

Tom Hardwick-Allan, 23, a recent graduate of the Slade, uses wood to make prints and sculptures inspired by memories of the natural world. He lives in Limbo, a shared studio and project space in south London founded by Slade students. Hardwick-Allan, like thousands of other artists across the world, is currently in lockdown in his studio until further notice, working as best as he can.

The son of a postman from rural Derbyshire, Hardwick-Allan was able to study at a top art school in London thanks to the Post Office’s POOBI (Post Office Orphans Benevolent Institution) bursary scheme. “Most people from less advantaged backgrounds feel discouraged from entering. There seems to be a divide,” Hardwick-Allen says. “The exclusion is intentional,” he feels. “A certain kind of conservatism is being reapplied.”

Some of his woodcut sculptures were included in Breathless/London Art Now, an exhibition of works by 16 young artists at the Ca’ Pesaro Galleria Internazionale d’Arte Moderna in Venice that tried to recreate the spirit of Sensation. Co-selected by Rosenthal, who is now a freelance curator, the show opened in October but closed the following month owing to catastrophic flooding.

“There’s a huge amount of energy among young people, I think. I’m sure there’s as much energy in London as there was in the days of Sensation,” says the ever-enthusiastic Rosenthal. Though, he added: “Maybe there are no stars like Damien Hirst. It goes in generations.”

But has London’s contemporary art scene become more gentrified since the glory days of the YBAs? “Yes and no. People who want to get through somehow find a way through,” Rosenthal insists, speaking before London succumbed to lockdown.

Once creative life re-normalises to an extent, the latest generation of young British artists will have no shortage of new subjects and topics to address. After the catastrophe of coronavirus, they may be working in a society that increasingly perceives what they do as a “low-value” occupation.

“It is too early to tell how this crisis might affect students from less well-off backgrounds. However, the pandemic has underlined the inequalities that are rife in our society,” Biderman says. “Freelancing as an artist or designer has never been more difficult than at this moment.”

For the time being, at least the perception is that artists have plenty of time to make art. That is, if they can afford to.