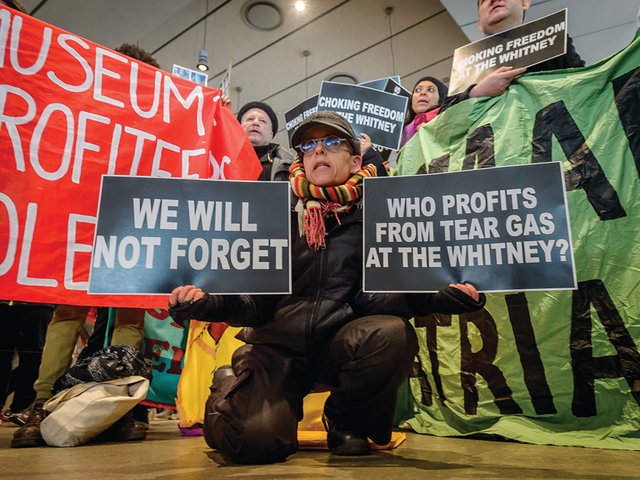

There is a disturbing comfort in political polarities. It can be appealing as they tend to be simple to understand, they ask us to make a choice, and encourage us to feel righteous in our decision. This dynamic is as predictable in the art world as it is in politics. Take, for example, some recent events as described in your article, “Philanthropy, but at what price? US museums wake up to public’s ethical concerns,” (The Art Newspaper, September 2019, p1). A cultural institution (Whitney Museum), an antagonist (an ultra-wealthy trustee who owns a company that makes tear gas canisters) and a group of protagonists (artist/activists who call out the trustee and withdraw art from an exhibition to pressure him to resign)—all acting in a predictable manner. The subsequent resignation of the board member, Warren Kanders, provides a resolution to the story. The forces for good win. It is a script that will play out again: the good, the bad and a surrender. But what was really accomplished? Was it really a victory for righteousness or simply a performance of it?

The artists do have legitimate points, particularly if they are asking us all to be held to a higher standard, and holding themselves to the same standard. But many artists are also benefiting from the capital-rich art market. The extreme consolidation of wealth is not just happening for the ultra-rich but also with many artists who are selling their works on a national or global basis.

Do we doubt that the wealth of many of these collectors may come from what some consider morally compromised sources? It is complex: when is a fortune tainted and who gets to decide?

Where is the art?

Lost in this conversation is the art itself and, to state the obvious, art museums are fundamentally about art. But they are equally about audiences and about learning. The narratives of our contemporary culture and our histories are often being negotiated within the walls of our museums. Yes, the museum of today is multifaceted and evolving; we are and should continue to be catalysts for important conversations. The value of exceptional works of art is often that they help us see ourselves and others in a new light. They help us negotiate our shared futures.

Museum curators and directors should be more assertive in making independent judgements about what is important, rather than accepting the verdict of the art market and collectors (as does happen, though we are often reluctant to admit it). The work of Rebecca Belmore (an Anishinaabe artist) resonates with the very international audiences here in Toronto, even though she lacks representation by a New York gallery.

Likewise, we can learn from juxtapositions between the art of today and the art of the past. A work by Kara Walker currently installed at the Art Gallery of Ontario can help us understand the sculpture of the Italian Renaissance master Gian Lorenzo Bernini with which it is juxtaposed, and vice versa. It is about the dialogue between works of art and time periods that good curation enables. Seeing great art can be enlightening. But it is also complex, and that’s the point.

Many artists are also benefiting from the capital-rich art market

I want to advocate for us to acknowledge the complexity of our time and not hide in simple political polarities. I firmly believe that if we focus on extraordinary works of art, museums can help build a common ground for us to explore the most important issues of our times. This will require greater independence from the art market by museums and collectors. It will require our culture not to mistake the cost of a work of art for its importance. It will require diversity and thoughtfulness at all levels of cultural institutions.

We need to work to identify the significant artists and develop knowledge before presenting it to our public in a compelling manner. At the end of the day, bringing audiences and art together is at the heart of what we strive to do. It might sound idealistic to advocate for extraordinary art—and its ability to change the world—but art museums should help us experience the world and ourselves in a more nuanced, more empathetic, more glorious and perhaps more radical way. To achieve that will require us to recognise that all of us—directors, trustees, curators, artists and the public—are multifaceted and complex, too.

Stephan Jost is the Michael and Sonja Koerner director and chief executive officer of the Art Gallery of Ontario