This article was featured in our Art Market Eye newsletter. For monthly commentary, insights and analysis from our art market experts straight to your inbox, sign up here.

“If all the museums start selling their collections, they are going to flood the market.” So said the dealer and collector Adam Lindemann, speaking to Josh Baer on his No Reserve show this month. And: “I do believe there are lots more works of art to come [for sale],” responded Marc Porter, the president of Christie’s Americas, who also featured in No Reserve.

It is no secret that museums are in crisis worldwide, facing a massive collapse in revenue caused by the forced shutdown at the beginning of the year and meagre visitor numbers since reopening.

In the US, the American Association of Museum Directors (AAMD) relaxed its rules on deacesssioning in April, granting a two-year “window” for selling to increasingly beleaguered museums. AAMD is allowing the money raised to pay for the direct care of the collection, and not just compulsorily ploughed back into buying other works.

Museums have leapt on this opportunity, even if some deny it is to keep the lights on but rather to diversify their collections. So far, art museums in Brooklyn, Syracuse (the Everson), Indianapolis, Fort Worth, Baltimore, Monclair, Laguna Beach and Springfield have all put up works for sale.

“Museum deaccessions come in two categories,” Porter says. “The first is the traditional paring of a collection, which has always existed—but now is used to diversify towards works by artists of colour, women artists and living artists. The second is the use of the proceeds of such sales for collection maintenance, which is a reflection of these economic times. This is absolutely a change in the market."

The market generally loves deaccessioned works; museum provenance adds the lustre of validation, and consequently monetary value. But will there just be too many of these works on the block in the coming months, and will there be enough buyers for them? Will works by dead white male artists (which is almost invariably the case) have the same attraction for those buyers? And finally, with an inevitably smaller market due to the crisis, can prices be sustained?

Nick Maclean, a secondary market dealer based in London, is positive: “There are still plenty of collectors out there to absorb these works. As long as the estimates remain conservative, I am not worried for the outcomes,” he says.

Spencer Ewen of the art advisors Gurr Johns agrees, but with some provisos: “My view is that the appetite to buy is there, but museums must be cautious when making their choices. The outcomes will depend on what they choose to sell; certain compositions and subjects, such as more inaccessible religious works, won’t sell so easily. And to an extent the market will self-regulate: if the market gets to boiling point, we would advise vendors accordingly.”

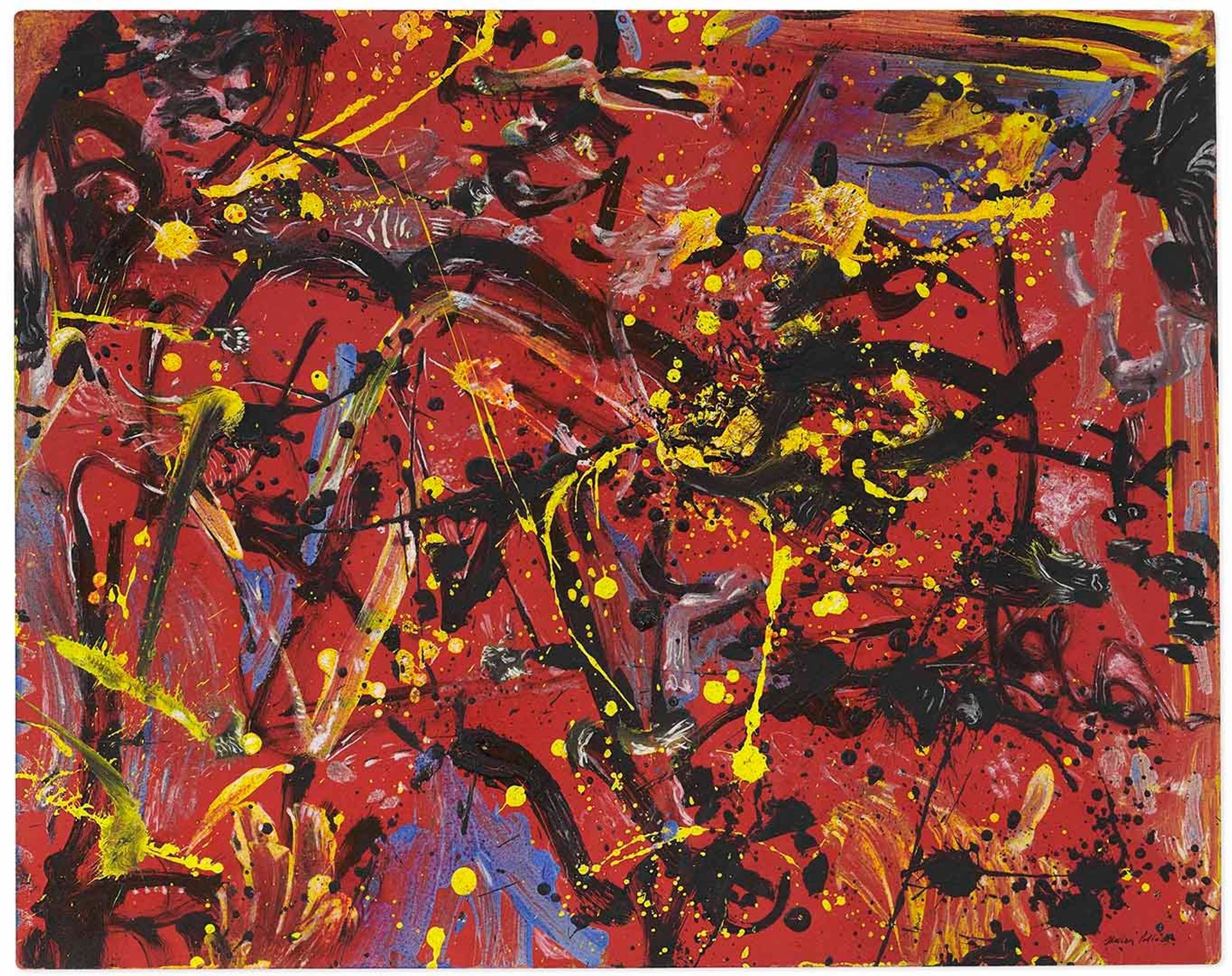

Jackson Pollock, Red Composition (1946), sold at Christie's for $12m © Christie's Images Ltd. 2020

For the moment, all is going reasonably well. While Everson’s Jackson Pollock [Red Composition, 1946] only made low estimate at $12m, the Brooklyn Museum of Art clocked up $6.8m from ten of 12 works consigned to Christie’s, the bulk represented by just one painting, Cranach the Elder’s Lucrecia (1530s) which doubled estimate at $5.07m.

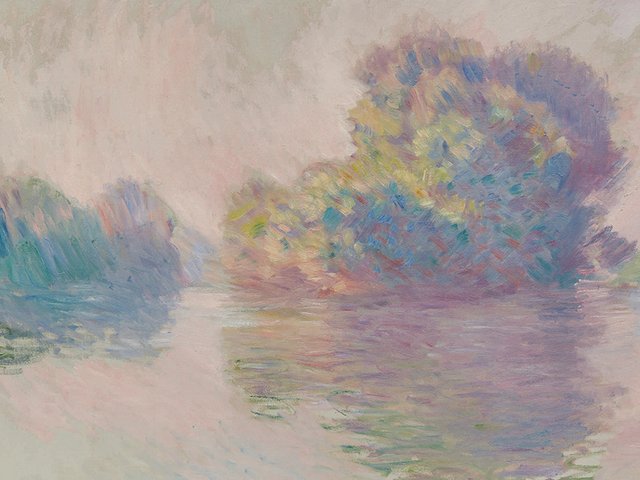

The day after that sale, however, the museum announced further disposals, this time at Sotheby’s, including works by Claude Monet, Edgar Degas, Joan Miró and Henri Matisse. Which rather bears out the fears of James H. Duff, the past chair of the Professional Issues Committee of the AAMD, speaking on the ARTscoping podcast: “Museums may develop a taste for funds derived from sales of art,” he warned. Putting the toothpaste back in that tube, in 18 months’ time, may prove to be more difficult than it appears today.