Arthur Brand, the Dutch private art detective, says that he has more photographs of the Van Gogh landscape which was stolen in Laren on 30 March, during the coronavirus lockdown. Two of the images were published last week—one of a label on the reverse of the painting (establishing that it is the authentic painting) and the other which included a newspaper (establishing that the photographs are very recent).

When we asked Brand if he had received other photographs of the painting from his underworld source, he said it was “more than two”. When a request was then made to publish them, he politely declined, saying “I wish I could, but I can’t because it is still under investigation”. Brand says that he has a wide network and the photographs come from “a source who I cannot mention”.

Arthur Brand

Brand is a Dutch private detective who specialises in art crime. Often a controversial figure, partly because of his extensive range of contacts (including those in the criminal world), he has a string of successful recoveries to his credit. Brand says he is now putting his efforts into helping to recover the Van Gogh. He believes the photographs were circulated “to shop the painting around”—since those who hold the picture “must be searching for a buyer”.

The Parsonage Garden at Nuenen in the Spring (1884), owned by the Groninger Museum in the north of the Netherlands, was seized in a smash-and-grab raid from the Singer Laren museum, just outside Amsterdam. It had been on loan to Laren for an exhibition.

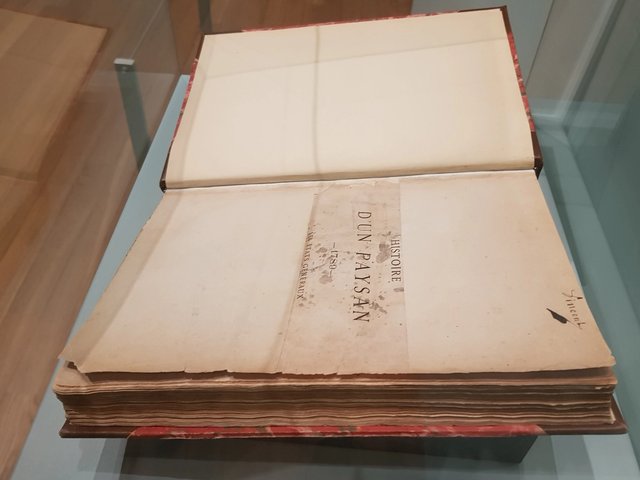

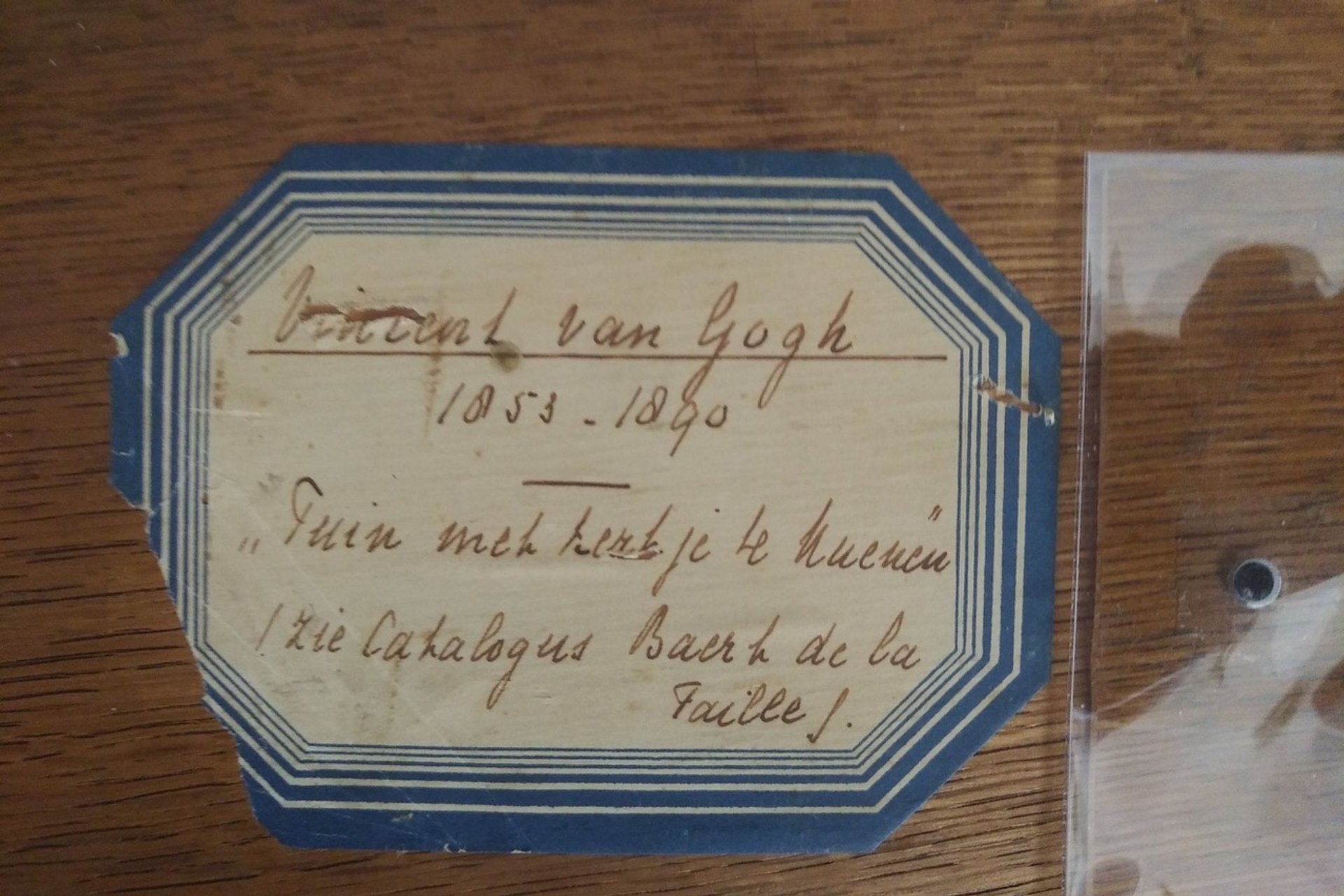

A label on the reverse of Van Gogh’s The Parsonage Garden at Nuenen in the Spring, owned by the Groninger Museum, Groningen

Andreas Blühm, the director of the Groninger Museum, told us that the photographs do seem to show the stolen picture: “The label on the reverse appears authentic and I believe it has never been published before—so this means that it is our painting in the photograph.” The label records the artist, title and a reference to the catalogue raisonné by Baart de la Faille.

The other published photograph, which is slightly blurred (presumably deliberately, to disguise details), shows the unframed painting on what appears to be a black bin liner. The picture has a white streak towards the bottom which could well be a scratch (the oil painting was done by Van Gogh on paper, which was later mounted on board).

Two publications have been unceremoniously placed on the sides of the painting (not very wisely from a conservation point of view): a newspaper and a book. Obviously the newspaper is there to establish dating, in the manner that human hostages are sometimes photographed, particularly when a ransom demand is being made.

The painting is almost certainly still in Europe, so it might seem surprising that the international edition of the New York Times was used (a publication which must have been slightly difficult to buy during lockdown). But it was included because the bottom of the front page has an article by Nina Siegal on the Laren theft.

The book, by Wilson Boldewijn, is Meesterdief (Master Thief)—a biography of Octave Durham, one of the pair of criminals who stole two paintings from the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam in 2002 (which were recovered four years ago). That theft, like the recent one in Laren, was a smash-and-grab raid. After the 2002 break-in the two Van Goghs circulated as currency among the Italian mafia.

But are the crooks now holding the Groninger painting trying to draw parallels with the manner in which it was stolen—or their plans for disposal?

It has been assumed that the photographs were taken to circulate in the underworld and tempt potential buyers who might want to the acquire the painting at a tiny fraction of its open-market value. But it is also possible that the photographs were not targeted at the underworld, but rather at investigating detectives. Linking the Laren and Amsterdam thefts may have been a deliberately misleading message sent out in an attempt to sow confusion, by wrongly suggesting an Italian mafia connection. Equally possible, the photographs may simply be an act of criminal bravado, to taunt detectives.

Blühm is unwilling to speculate, saying that “we are not going to try to interpret the meaning of the publication of the photographs—that is up to the police”. What he will say is that he is “relieved that the picture still survives”. And publication of the photographs suggests that the situation is fluid, offering hope for a successful recovery.

Other Van Gogh news

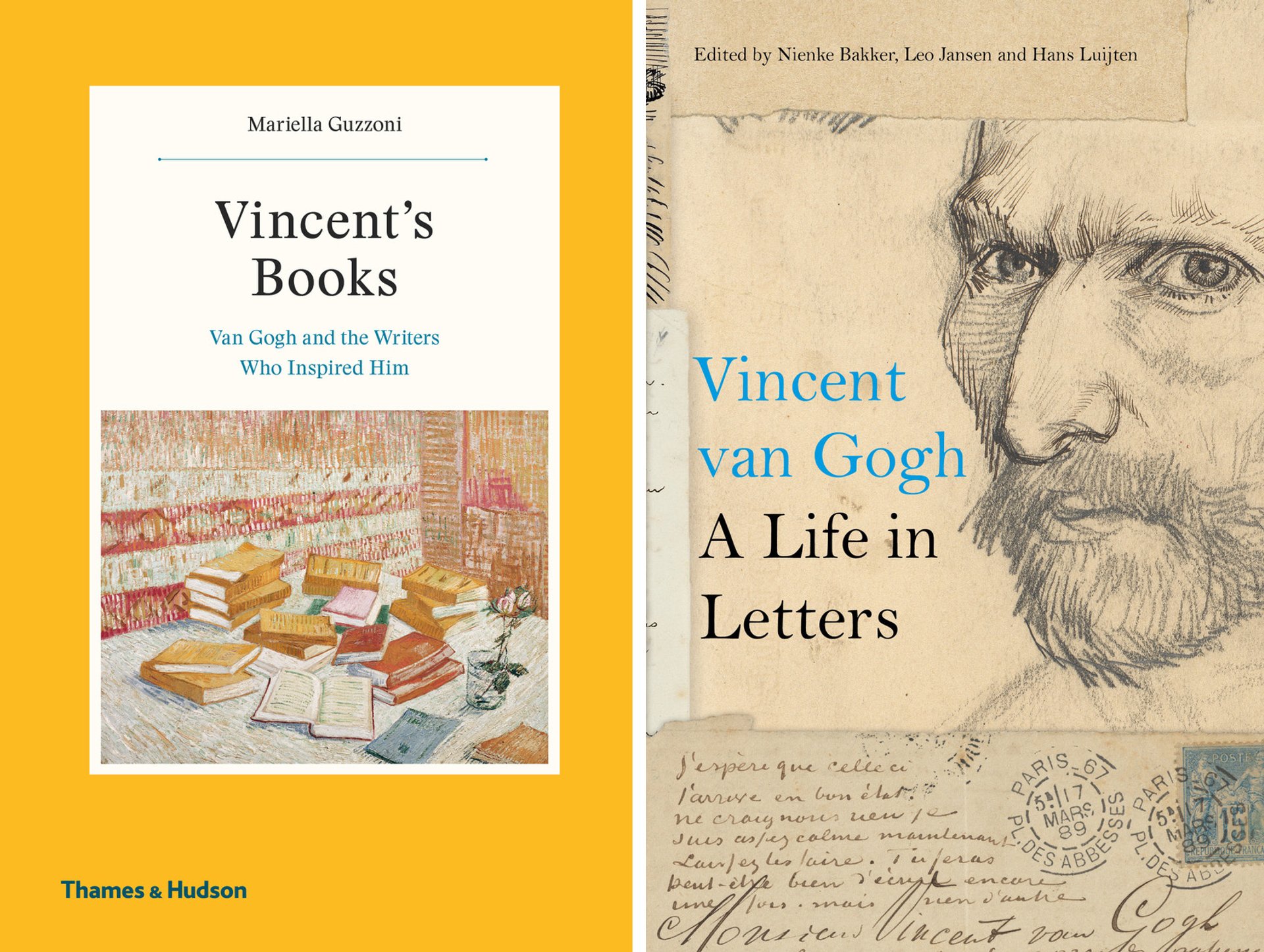

• Thames & Hudson will be publishing two new Van Gogh books on 2 July.

Vincent’s Books: Van Gogh and the Writers Who Inspired Him, by Mariella Guzzoni, is a detailed (and beautifully written) account of what the artist read—and how it influenced his art. Guzzoni’s basic source is Van Gogh’s letters, supplemented by her close study of the books themselves.

Vincent van Gogh: A Life in Letters, edited by Nienke Bakker, Leo Jansen and Hans Luijten, is a condensed version of the definitive six-volumes edition of Van Gogh’s letters, compiled by the Van Gogh Museum and published in 2009. An earlier condensed edition was released in 2014 by Yale University Press, as Vincent van Gogh: Ever Yours, the Essential Letters. The new Thames & Hudson version is considerably shorter (with 76 letters), but more attractively presented.

The covers of Thames & Hudson’s latest publications—Vincent’s Books: Van Gogh and the Writers Who Inspired Him and Vincent van Gogh: A Life in Letters Courtesy of Thames & Hudson

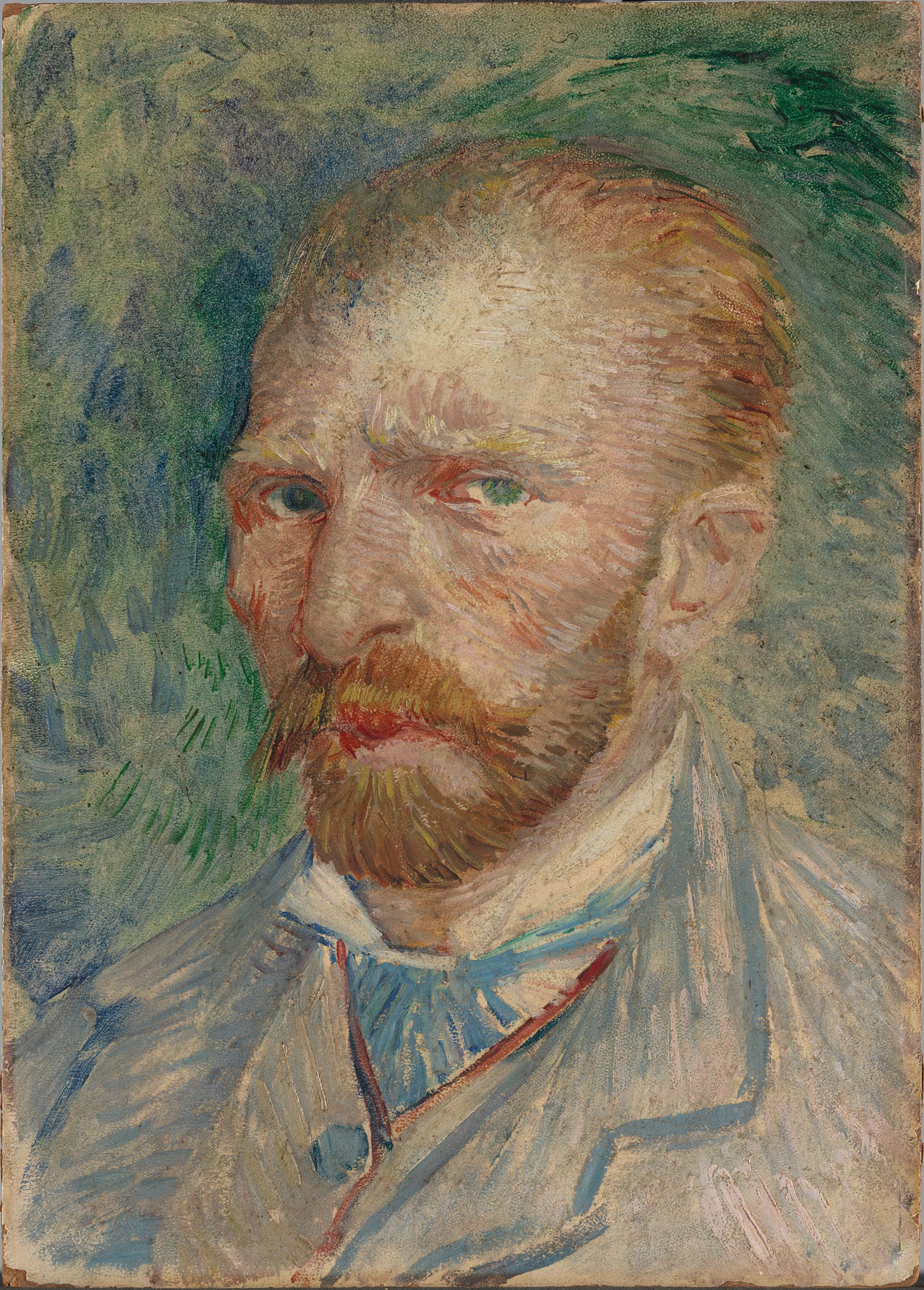

• It has just been confirmed that Finland’s Van Gogh exhibition is to go ahead in September, despite coronavirus problems. Becoming Van Gogh, with 40 works on loan from the Kröller-Müller Museum in Otterlo, will be at the Didrichsen Art Museum in Helsinki, from 5 September to 31 January 2021.

Vincent van Gogh’s Self-portrait (1887), which will go on loan from the Kröller-Müller Museum to the Helsinki exhibition Courtesy of the Kröller-Müller Museum