The list of British female painters working professionally before the 19th century is surprisingly long, given the constraints they faced. Standout names include Joan Carlile, Susannah-Penelope Rosse and Mary Moser. But only one, Maria Cosway, has been the subject of a major biography, and that mostly focused on her scandalous personal life. Now, however, a new biography of Mary Beale, the first commercially successful female British artist, has been written by Penelope Hunting, and will be published later this year. I’ve had a sneak preview—I wrote the foreword over Christmas—and can say that while it is a shame art history has taken over 300 years to do Beale’s life justice, it will be worth the wait.

Aside from reading about Beale, my only other art historical activity over the holidays was taking down a painting to accommodate our Christmas tree. Given the art-damaging capabilities of our cat (as described in November’s diary), I was more careful not to leave the painting on the kitchen table. The cat, Padme, has enjoyed her 15 minutes of fame; over the New Year she featured on America’s number-one chat show, The Late Show with Stephen Colbert. It is true that the media has exaggerated the story so that the painting, a portrait by John Michael Wright, was “completely destroyed” by Padme, when in fact the damage was repairable. By repute, the painting is now worthless. But on the plus side, never have so many people heard of Wright—a much underrated artist. There is no such thing as bad PR, even in art history.

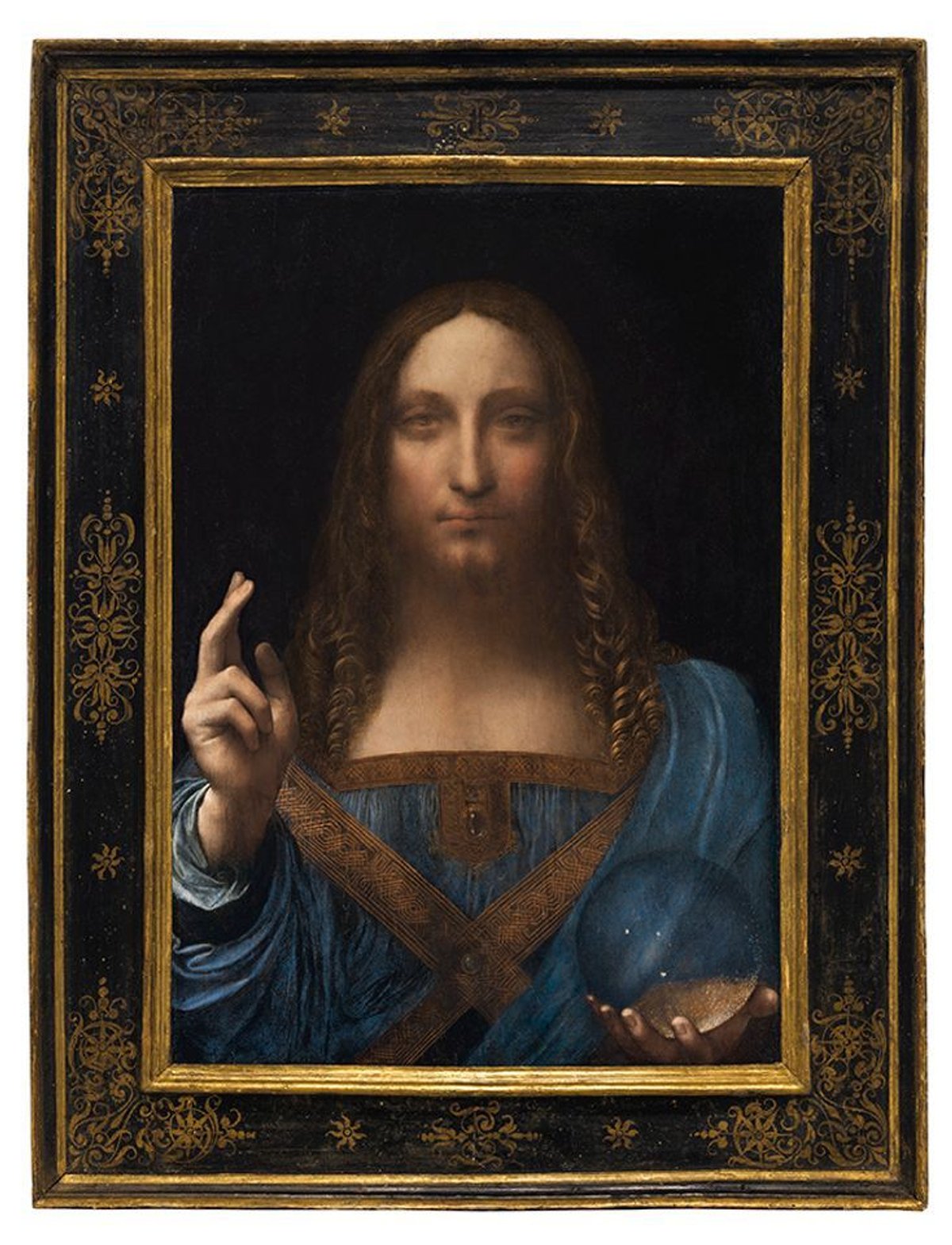

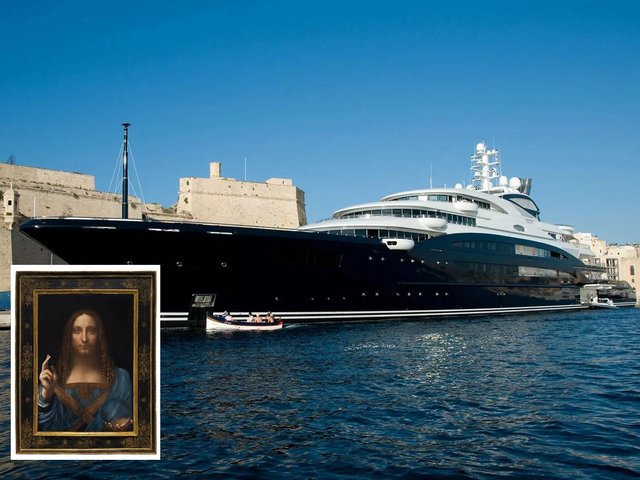

Or is there? Leonardo da Vinci’s $450m Salvator Mundi has been in the news again. The painting has an effortless ability to make headlines, with its clickbait blend of Leonardo, Jesus, attributional controversy and money. But now it has allegedly “disappeared” (with no news since its unveiling at Louvre Abu Dhabi was delayed) and, what is more, Donald Trump has been added to the mix. Was the painting, headlines asked, part of an Arab plot to both launder money and support Trump in the US presidential elections?

No. Nevertheless, the story went viral quicker than you can say fake news. The basic truth of all Salvator Mundi stories is less exciting; it is an important painting with a solid connection to Leonardo da Vinci, and many rich people want to own it. Its delayed appearance at Louvre Abu Dhabi most likely reflects Middle Eastern politics. But facts seem no longer to matter with the picture. Maybe this determination to speculate reveals nothing more than our fascination with all things Leonardo, but I suspect it is also because his accessibility makes it possible for everyone to have an opinion on his art.

The problem is, such opinions are often about social signalling rather than the art. Not that this only affects Leonardo. In the contemporary art world, the way to demonstrate one’s level of sophistication is to say how much you “get” even the most trivial or absurd work, like the canvas covered with row upon row of burnt toast that I saw in London last week, which cannot ever reveal anything more profound than the fact that the artist refused to change the setting on their toaster, but which will inevitably elicit from someone important the po-faced response, “actually I think that’s really interesting”, and thus become art.

In the Old Master world, it is the opposite; the way to show your superior knowledge is to say you don’t like something; to sneer and say that the painting’s a fake, or a copy, or a ruin, when most of us are simply not qualified to make such judgements. Perhaps revealing our ignorance is what art does best.