As the world around us seems to be departing ever further from the realms of normality, an exhibition devoted to artists making work guided by inexplicable forces beyond their rational control seems especially topical. Not Without My Ghosts explores the idea of the artist as a medium who channels imagery from other sources, whether external or subconscious, and is full of fantastic phantoms and haunting images, many of which are being given a rare public airing. What better show to see this Halloween weekend, which is its last at the Drawing Room in London, before touring to Sheffield, Swansea and Blackpool.

Not Without My Ghosts opens with the visionary heads that came to William Blake in the middle of the night—including the Spirit of Voltaire and the Ghost of a Flea, and extends through Victorian Spiritualism via Surrealist automatism and 60s counterculture. More spirit-raising, mediumistic creations include Sigmar Polke’s 1960’s Fire Head, apparently made under the instruction of mysterious “higher beings” and Susan Hiller’s 1970s experiments with automatic writing; as well as drawings made under hypnosis in the 1990s by Ann Lislegaard and Suzanne Treister’s records of her virtual Museum of Black Hole Spacetime Séance which took place in January 2020.

Madame Fondrillon's Dessin médianimique (1909) Courtesy Galerie 1900-2000, Paris

Although there are some big names here, the more obscure figures are as compelling. Alongside the writer-artist Victor Hugo’s exquisite 1850s séance drawing of spectral faces traced through the lattice of a piece of lace is a meticulously detailed, densely patterned pencil and crayon dessin médianimique made by the Spiritualist medium Madame Fondrillon in 1909. Very little is known about this mysterious figure except that she was greatly admired by Surrealism’s founder, André Breton, who saw her work as a precursor to the Surrealist practice of tapping into the subconscious using automatic, free association.

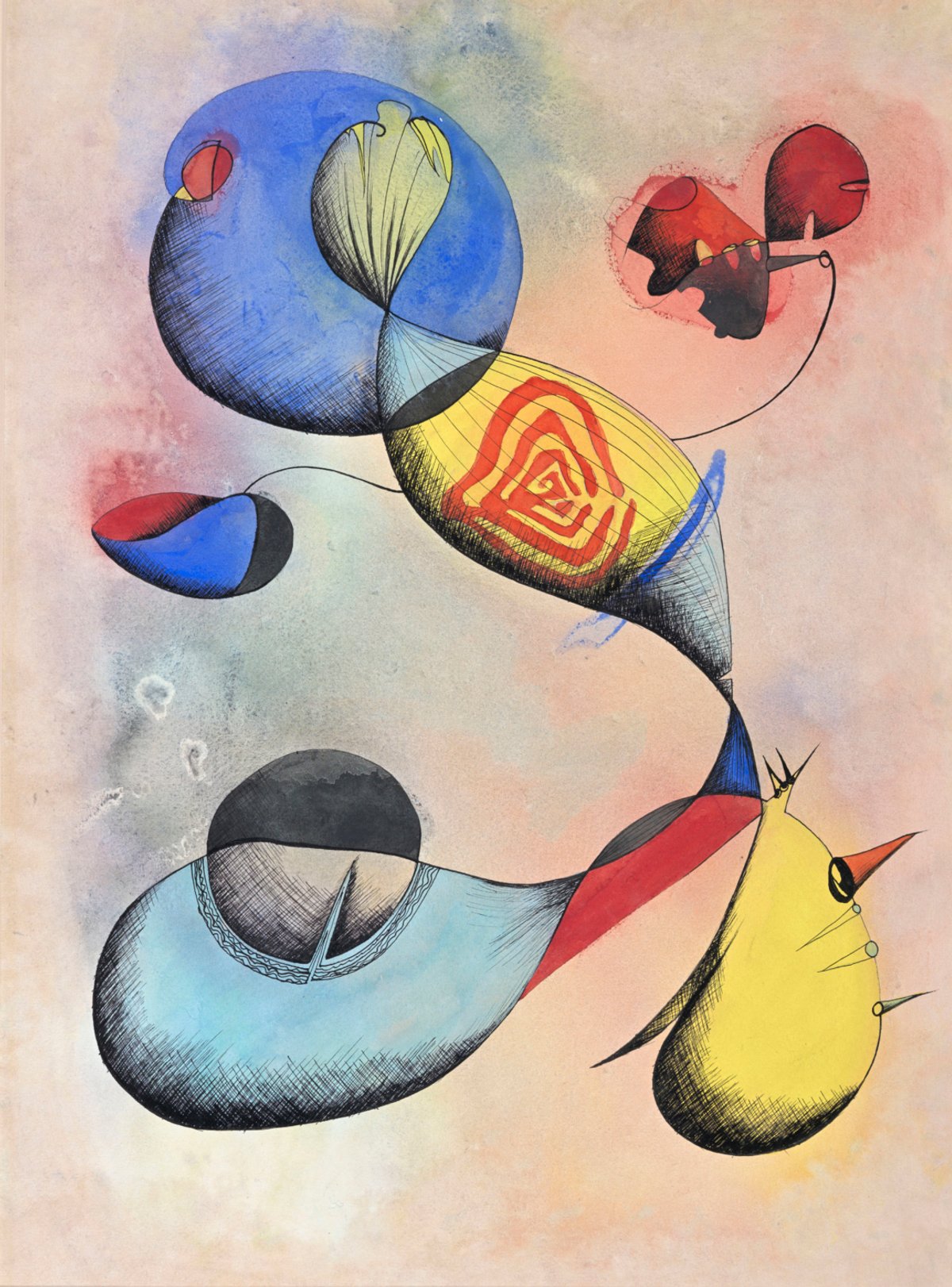

A more famous advocate of Surrealist automatism was André Masson, who is represented in this show by a calligraphic ink portrait of Benjamin Péret. His fellow self-taught Surrealist Yves Tanguy lays bare more Freudian recesses of the unconscious mind in a delicate 1931 drawing of a fragmented, spectral multi-breasted figure in a dessin automatique of 1931. There is also a vividly coloured cartoonish floating baby painted in the 1930s by Grace Pailthorpe, a Freudian psychoanalyst who, with her collaborator-companion Reuben Mednikoff, used their art practice to investigate the psycho-sexual nature of human behaviour.

Grace Pailthorpe's The Torment of Tantalus (1938)

Yet Surrealism and the art world in general have been less tolerant of the artists whose mediumistic activities tipped into occultism. Ithell Colquhoun—represented here by a luminous ink and watercolour work—was one of British Surrealism’s most original voices. But her use of Surrealist techniques to explore nature, magic and the occult led to her being expelled from the movement.

And his pencil self-portrait confirms that while Austin Osman Spare was a consummate draughtsman, after this much lauded early prodigy developed his own magical philosophy and became a disciple of Alistair "The Beast" Crowley, he was increasingly ostracised and died in impoverished obscurity in 1956. Another sidelined figure combining art, magic and the supernatural was the Los Angeles-based artist, poet and occultist Marjorie Cameron. She was a key presence in mid-20th-century West Coast counterculture and New Age communities, but worked in isolation, putting herself into a deep state of meditation to make translucent watercolours exploring arcane aspects of Egyptian astrology and reincarnation, which only now are gaining some recognition.

Barbara Honywood, Album Page XIV (around 1860s) © Bethlem Museum of the Mind

Another reason why much of this mediumistic work has been overlooked is because it was predominantly made by women. As female activists campaigned for equal rights and representation, Spiritualism frequently offered a parallel means to channel this collective energy. The Victorian Spiritualist movement was dominated by women working as mediums and conducting seances, but it also attracted leading feminists and human rights campaigners. While there were close parallels between the sisterhood of Spiritualism and the Suffragette movement, this independence and autonomy could be both liberating and isolating. Being so closely associated with the feminine exposed Spiritualism to satire and mockery, with spirit-guided artworks subject to scepticism and rarely assessed in their own right.

Hence the neglect of the trio of Victorian Spiritualist artists represented here, especially the vivid sinuous abstract skeins, spirals and loops executed in the 1860s by Georgiana Houghton. Or as she claimed, by the hands of the dead guiding her own. Her richly coloured intricate works look like nothing else in art history, with the visionary non-figurative art made by Houghton and her spiritual pupil Barbara Honywood predating the officially sanctioned (male) pioneers of abstraction by more than fifty years. And let’s not forget that the supernatural had its part to play here too: Piet Mondrian was a Theosophist and Kandinsky wrote On the Spiritual in Art.

Georgiana Houghton's The Spiritual Crown of Annie Mary Howitt Watts (1867) Courtesy georgianahoughton.com

The third spiritualist artist in the show, Anna Mary Howitt, further underlines the close relationship between spirit art and feminism with her paintings and drawings that create pantheons of deities, often with a Christ-like female at the centre. This central feminine presence was inspired by Howitt’s apparent belief in the female manifestation of the divine, or, as she described it, the “mother power’ which she believed guided her creativity.

Not without my Ghosts doesn’t claim to be definitive, and describes itself as "a primer not a treaty". Nonetheless, this tightly curated show contains quite enough to confirm that an embracing of the irrational and the spiritual has been a crucial—if under-acknowledged—influence on so many major art movements of the last two centuries. It also recognises the central importance of female artists in making art that embraces a mediumistic approach and in exploring these new forms of visual expression even if, along the way, their role has often been underplayed or forgotten. Unpredictable, spontaneous and unconventional, these otherworldly visions need to be considered as a central theme both within feminism and in Western art history, especially with so many artists continuing to pick up on their reverberations today. Happy Halloween!

- •