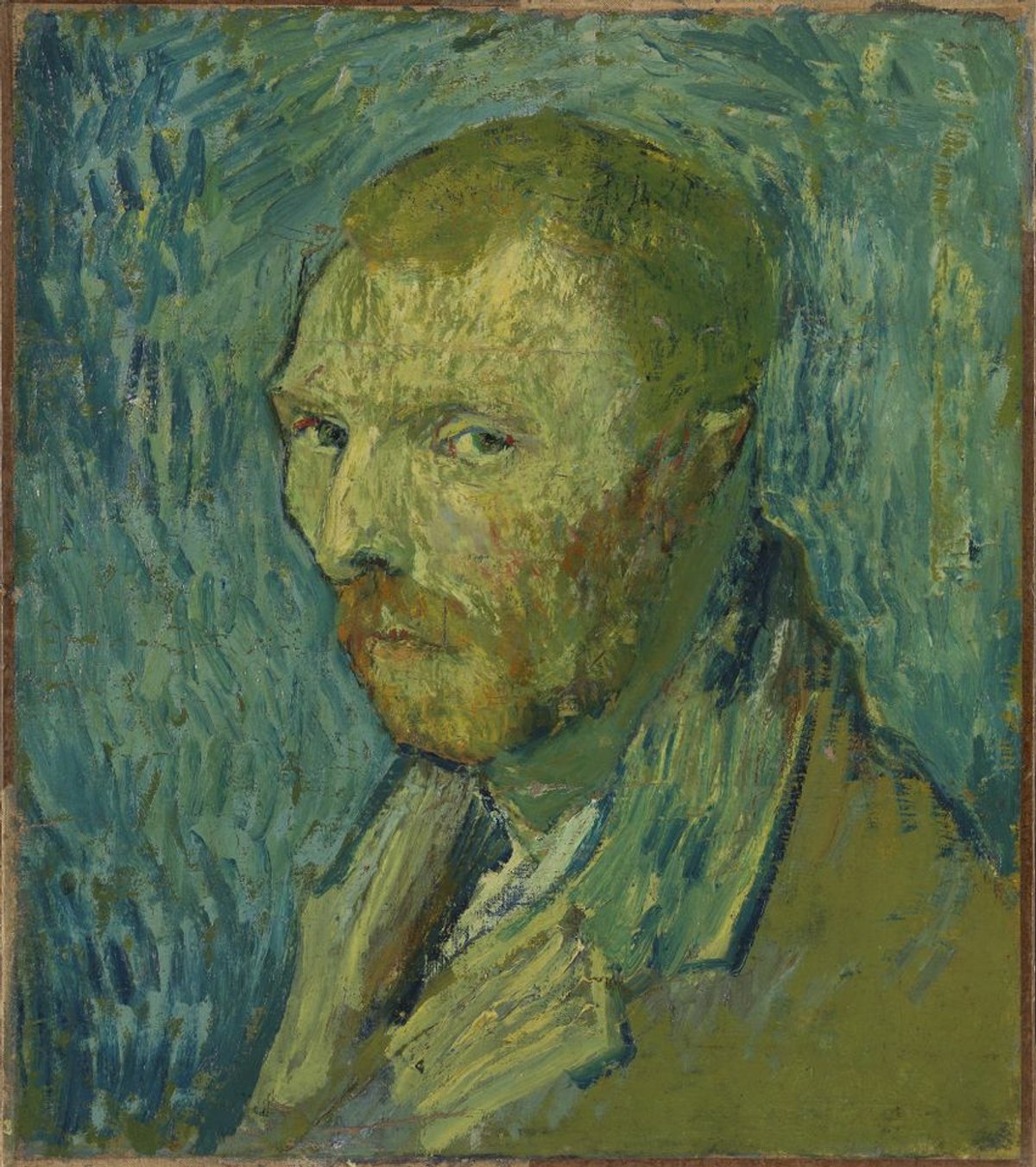

A group of Van Goghs which had been dismissed as likely fakes have been reattributed to the artist in recent years. The 1889 Self-Portrait from Oslo’s National Museum is only the latest example. On Monday the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam announced that a five-year research project had concluded that the Oslo painting is now the only known one made by the artist during a psychotic attack—so it tells us something new about his tormented condition.

A very important, but almost unnoticed change has been going on in Van Gogh studies. Until recently, the artist’s oeuvre had been reduced, but now it is being expanded again.

The question of fake Van Goghs was brought to international attention by The Art Newspaper in 1997, when we revealed that “at least 45 Van Goghs may well be fakes”. This was based on the conclusions of the late Jan Hulsker, the author of a revised catalogue of the artist’s oeuvre, who was questioning works that he had earlier included in the first edition of The Complete Van Gogh in 1980. In the late 1990s and early 2000s dozens of works began to be seriously doubted, with some being downgraded by leading museums.

Now the pendulum has swung the other way, with a significant number of the questionable works being accepted once again. The main reason for the change is the systematic study of paintings and drawings by specialists at the Van Gogh Museum. Until then, attributional issues tended to be the preserve of individual experts who would often make judgements based on connoisseurship. The museum has the experienced curators and researchers, the archives and documentation, and skilled conservators with the latest scientific equipment.

There are fascinating parallels with the oeuvre of the other very great Dutch artist: Rembrandt. During the early years of the 20th century the number of accepted Rembrandts steadily increased, with Abraham Bredius recording 624 paintings in his 1937 catalogue. The Rembrandt Research Project, set up in 1968, took a much more restrictive view, with their team believing that the true number was closer to 250 authentic works. Once again, the pendulum has now swung back and Ernst van de Wetering, the leading specialist today, has now reinstated 70 paintings which had been rejected earlier by the research project.

So what are the new reattributions the additions to Van Gogh’s accepted oeuvre in the past decade?

Vincent van Gogh, Vase of Poppies (1886), Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Hartford, Connecticut, Bequest of Anne Parrish Titzell (F279)

Vase of Poppies (1886), at the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art in Hartford, Connecticut, was authenticated last March, after being banished to storage for 30 years. Based on the canvas, ground layer, pigments and style, the Amsterdam museum specialists now believe it was painted by Van Gogh in Paris. X-rays reveal that beneath the paint surface is a hidden image of a portrait, suggesting that the artist reused the canvas to save money.

Vincent van Gogh’s Vase with Carnations (summer 1886) Courtesy of Wikicommons (F243)

Vase with Carnations (summer 1886), at the Detroit Institute of Arts, has been quietly upgraded as an authentic Van Gogh. In 2010 the painting was included in the museum’s exhibition Fakes, Forgeries and Mysteries, as of an uncertain status and either painted by the artist in 1886 or by an imitator before the 1920s. But we can report that a few years ago it was examined by the Van Gogh Museum, which confirmed its authenticity. The painting had been bequeathed to the museum in 1990 for possible resale, but last August it was formally accessioned into the collection - so there are no plans to put it on the market.

Vincent van Gogh’s Still life with Meadow Flowers and Roses (1886-87) © 2020 Collection Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, the Netherlands, purchased with support from the Rembrandt Association. Photography by Rik Klein Gotink, Harderwijk (F278)

Still life with Meadow Flowers and Roses (1886-87), at the Kröller-Müller Museum in Otterlo, was downgraded in their 2003 collection catalogue as “formerly attributed to Van Gogh”. Research by the Van Gogh Museum led to it being accepted again in 2012. Part of the evidence for the reattribution was an x-ray analysis of another image beneath, which had been painted over when the canvas was reused. Van Gogh had originally depicted a scene of a pair of artists’ models wrestling.

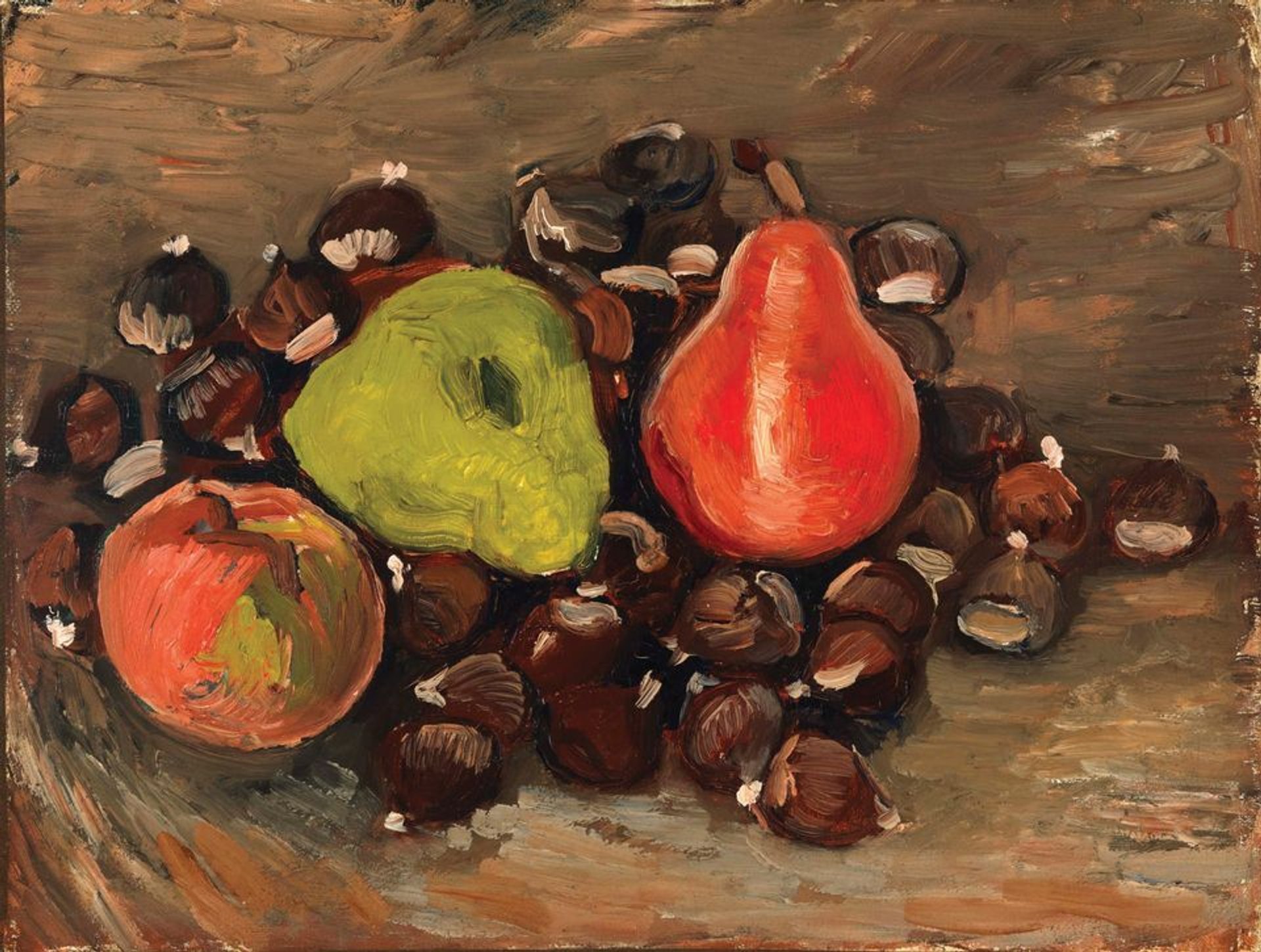

Vincent van Gogh's Still Life with Fruit and Chestnuts (autumn 1886) © Courtesy of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco (F-)

Still Life with Fruit and Chestnuts (autumn 1886), at the Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco, was excluded from the Van Gogh catalogues by Jacob-Baart de la Faille and Hulsker. For most of time since the 1980s it has been off display, dismissed as a fake. But last year research by the Van Gogh Museum authenticated the work, revealing that it too had been painted over an earlier work, a portrait.

Vincent van Gogh’s The Blute-Fin Mill (autumn 1886) © Collection Museum de Fundatie, Zwolle (F-)

The Blute-Fin Mill (autumn 1886), depicting part of the entertainment complex at the top of Montmartre, was dismissed as a fake and had been excluded from the catalogues by de la Faille and Hulsker. The main reason for the doubts is the clumsy depiction of the people on the steps. The painting had been acquired in 1975 for the Museum de Fundatie in the eastern Dutch town of Zwolle. An examination by the Van Gogh Museum in 2010 confirmed its authenticity.

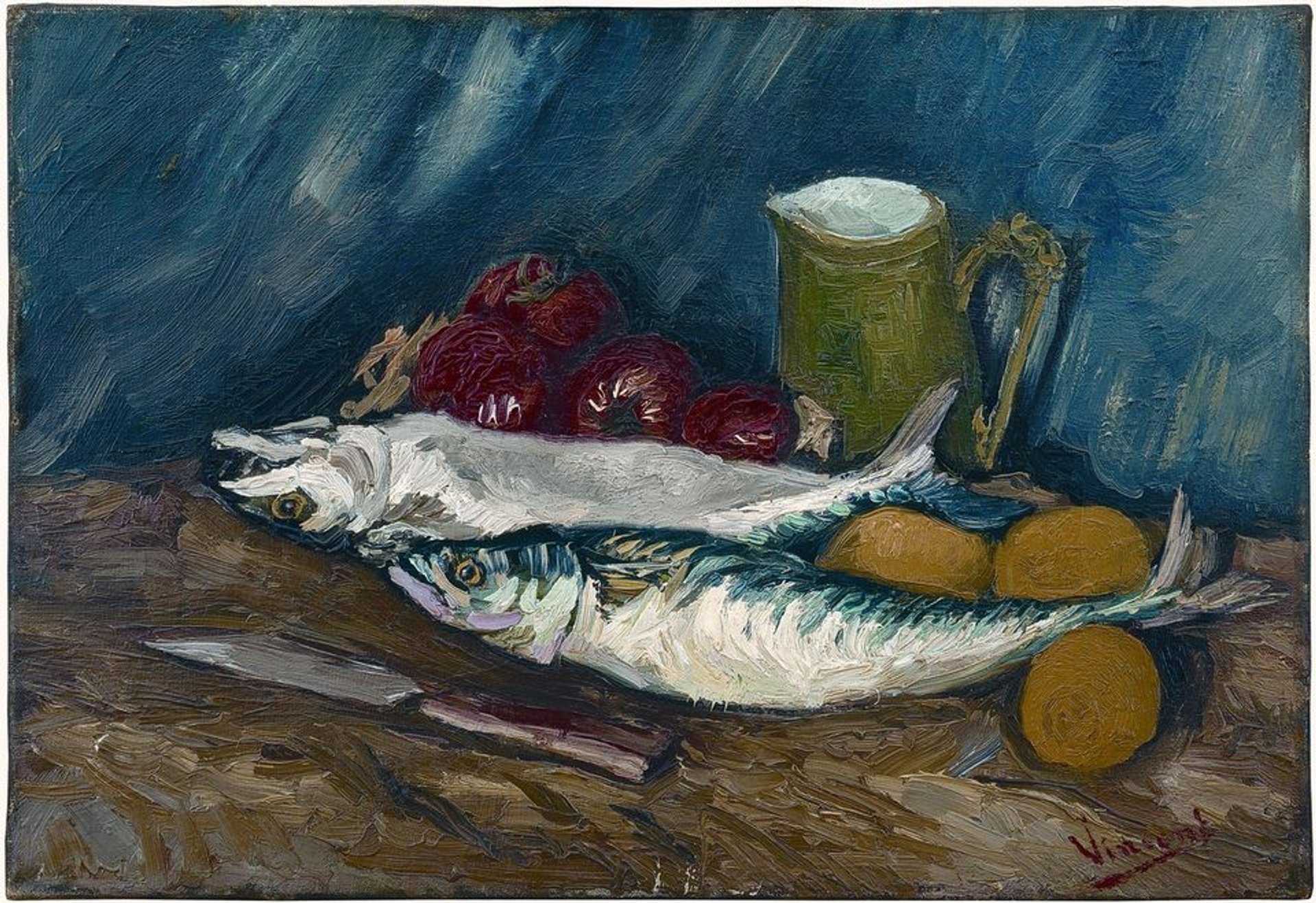

Vincent van Gogh’s Still Life with Mackerels and Tomatoes (summer 1886) ©Sammlung Oskar Reinhart “Am Römerholz”, Winterthur (F285)

Still Life with Mackerels and Tomatoes (1886) (1886) is still in limbo, but is likely to be authenticated as a definite Van Gogh. It belongs to the Oskar Reinhart “Am Römerholz” collection in Winterthur, outside Zurich, once privately owned but now open to the public. The painting was downgraded by the Van Gogh specialist Roland Dorn in the collection’s own 2003 scholarly catalogue, who described it as a “true forgery”. The Van Gogh Museum’s senior researcher Louis van Tilborgh has written that although its authenticity has been doubted, “that view needs closer examination”.

Vincent van Gogh’s View of Auvers-sur-Oise (May-July 1890) Credit: Museum of Art, Rhode Island School of Design, Providence. Given in memory of Miss Dorothy Sturges by a Friend. 35.770 (F800)

View of Auvers-sur-Oise (May-July 1890), at the Rhode Island School of Design, was downgraded in the 1970s, banished to the stores and dismissed as “a pastiche by an unknown hand”. Research by the Van Gogh Museum confirmed its authenticity in 2016.

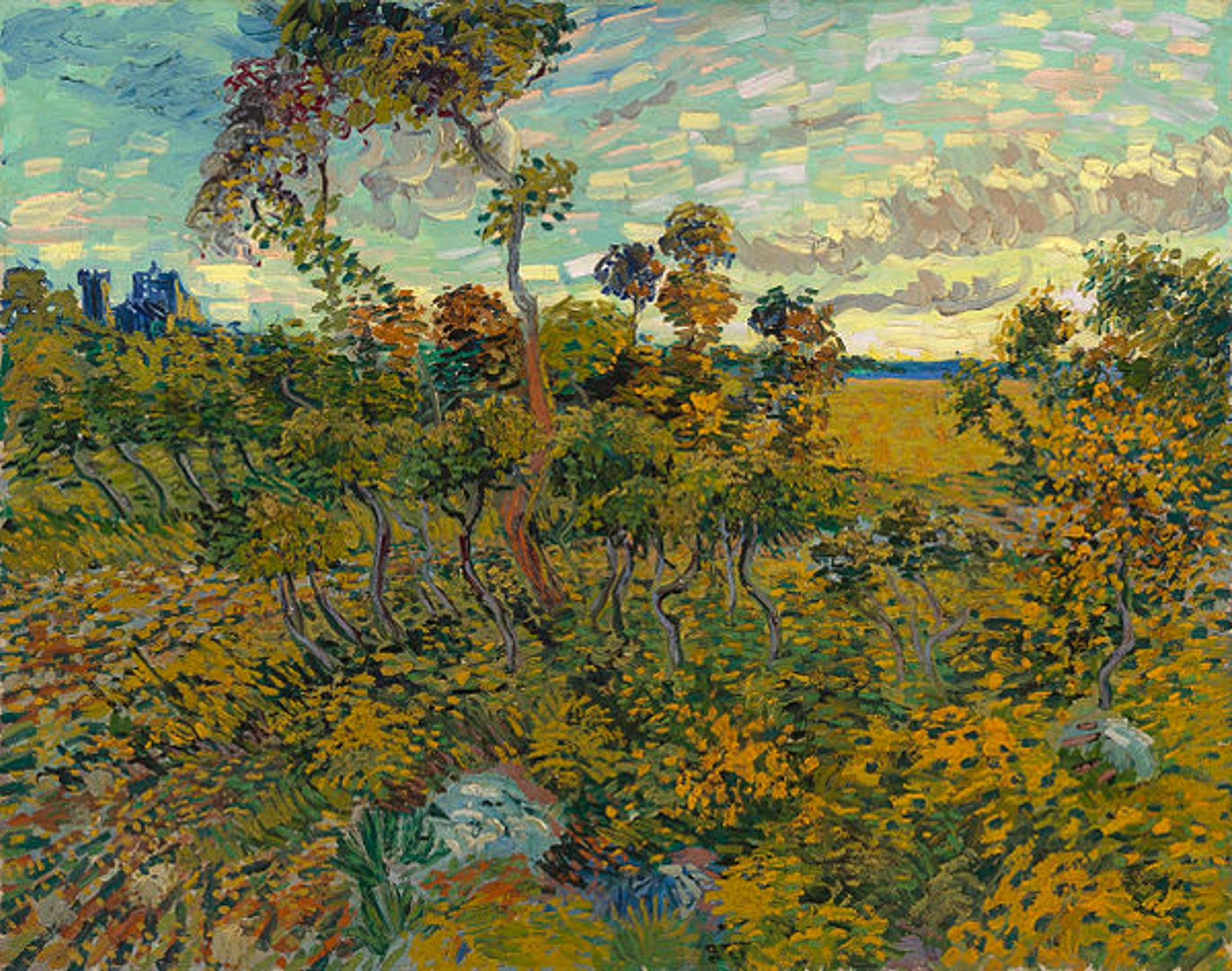

Vincent van Gogh’s Sunset at Montmajour (July 1888) © Private Collection. Wikicommons

Sunset at Montmajour (July 1888) is unlike the other reattributions, in that the painting had apparently disappeared for a century and was assumed lost. The owners had taken it to the Van Gogh Museum in 1991, but were then privately told it was not authentic. A few years ago it was sent back to the museum for a second opinion. In 2013 it was declared to be authentic, going on display at the museum for much of the time until July 2018. Belonging to an anonymous owner, it has not been seen since.

It is interesting that all the nine recently reattributed works are from Van Gogh’s last four years, when he was working in France (1886-90). Most are from his two years in Paris. Few letters from his Paris period survive, since he was living with his main correspondent, his brother Theo, depriving us of a key source of information. Stylistically, it was a time of great change in Van Gogh’s art, as he discovered Impressionism and his palette lightened. This makes it much more difficult to establish authenticity for the Paris paintings.

Finally, it should be pointed out that not all experts accept the judgements on these nine paintings by the Van Gogh Museum. Walter Feilchenfeldt, a distinguished Zurich-based specialist and author of Vincent van Gogh: Complete Paintings 1886-1890, believes that many of the works we have discussed are not authentic. Further information on the museum’s authentication process is available on its website.

• Vase of Poppies, Vase with Carnations and Still life with Meadow Flowers and Roses are currently on loan to Van Gogh: Still Lifes at the Museum Barberini in Potsdam, outside Berlin (until 2 February). Still Life with Fruit and Chestnuts and The Blute-Fin Mill are in Making Van Gogh: A German Love Story at Frankfurt’s Städel Museum (until 16 February). View of Auvers-sur-Oise is to be lent to the coming exhibition on Van Gogh in America at the Detroit Institute of Arts (21 June-27 September 2020).