Napoleon’s Plunder and the Theft of Veronese’s Feast, Cynthia Saltzman, Thames & Hudson (US: Farrar, Straus and Giroux), 320pp, £25 (hb)

The fact that a number of the world-famous works housed at the Musée du Louvre were looted by Napoleon Bonaparte has perhaps slipped under the radar for lovers of the Parisian museum. Napoleon’s Plunder charts Bonaparte’s ransacking of Italy and Spain, among other countries, in the late 18th century, exploring “one of the most spectacular art appropriation campaigns in history”. The looted haul of masterpieces by artists such as Leonardo da Vinci, Raphael and Titian were displayed at the Louvre in a powerful show of the emperor’s strength (some works were returned to their home countries after the Battle of Waterloo in 1815). In 1797, Napoleon removed The Wedding Feast at Cana (1563) by Paolo Veronese from the refectory of San Giorgio Maggiore in Venice. Cynthia Saltzman relays how the canvas was rolled up around a cylinder, sent to France, and later patched-up and retouched. The vast painting remains at the Louvre to this day and hangs in the same gallery (the Salle des États) as the Mona Lisa.

Heavy going... Chinese Art: The Impossible Collection by Adrian Cheng and John Dodelande weighs in at a whopping 9kg Courtesy of Assouline

Chinese Art, The Impossible Collection, Adrian Cheng and John Dodelande, Assouline, 194pp, $895 (hb)

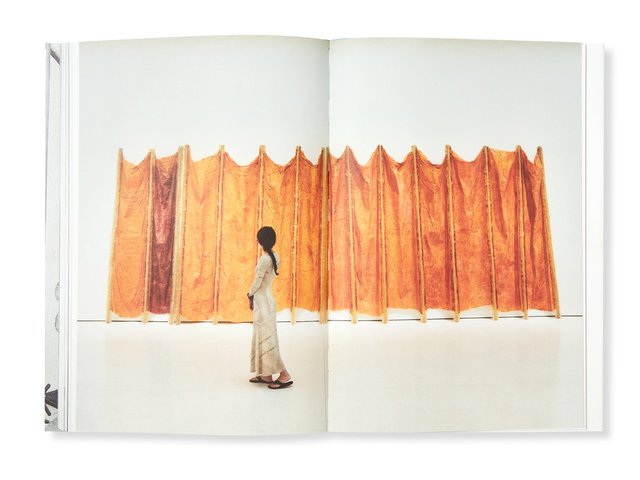

The collectors Adrian Cheng and John Dodelande present their dream collection in the latest publication in Assouline’s Ultimate series, which focuses on Chinese art over the past century. Both authors present a highly subjective selection of 100 works of Chinese Modern and contemporary art, including Zhao Bandi's Butterfly (1990), Zhang Huan’s Family Tree (2000) and Xu Bing's Tianshu (A Book from the Sky) (1987-91). The authors say in a statement: “This is not an encyclopaedia of contemporary Chinese art… It was a near impossible task to winnow the selection down to just a hundred.” Scholarly essays by Philip Tinari, the director and chief executive of Beijing’s UCCA Center for Contemporary Art, and Alexandra Munroe, the senior curator of Asian art at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, are included. Priced at $895, and weighing 9kg, the publishers describe the tome as a “work of art in its own right”.

Under Discussion: The Encyclopedic Museum, Donatien Grau, Getty Publications, 256pp, £27.00 (pb)

The scholar Donatien Grau dissects the origins, aims and prospects of encyclopaedic museums founded in Europe in the 18th century and later in the US. Grau asks in the introduction: “How can such a museum address its own history, and what should it do with its collections of questionable origins?” He goes on to point out that now “the encyclopaedic model is under considerable pressure, as since the 1970s it has been tied into the debate on restitutions”. High-profile contributors include Max Hollein, the director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, who tells Grau that “as an effect of globalisation… it becomes more and more obvious that it’s utterly impossible to be an encyclopaedic museum of the world and for the world”. Amit Sood, the director of Google’s Cultural Institute, says that “we have not thought of what we do in terms of a museum that has a responsibility and an authority to tell stories… Boundaries need to be broken. Online, there are no boundaries.”

Count Moïse de Camondo with his son Nissem © MAD Paris / Photo: Jean-Marie del Moral

Letters to Camondo, Edmund de Waal, Chatto & Windus, 192pp, £14.99 (hb)

The ceramicist Edmund de Waal blends fact and fiction in the follow-up to his 2010 family memoir, The Hare With Amber Eyes. De Waal describes his latest tome as “a haunting sequence of imagined letters to the Count Moïse de Camondo, the owner of a Parisian palace filled with beautiful objects, turned into a memorial for his lost son.” De Waal explores the life and times of the count, a scion of a Constantinople banking family known as the “Rothschilds of the East”. The Jewish banker commissioned the architect René Sergent to build a mansion at Versailles, where he could house his prestigious collection of 18th-century art and antiques. The house became a memorial to his son and was bequeathed on his death in 1935 to the French state. Through 58 imaginary letters to the late Camondo, De Waal tells the story of the man’s life and death, his house, his collections, and what became of his legacy.

Taking Care, Aliza Nisenbaum, Tate Publishing, 64pp, £10.00 (pb)

In the summer of 2020, the Mexican artist Aliza Nisenbaum contacted key members of National Health Service (NHS) staff in the Liverpool area, who agreed to sit for portraits. The participants, who have worked throughout the pandemic, include a professor of outbreak medicine, a respiratory doctor, and a student nurse from a family of nurses who all chose to return to frontline work. Nisenbaum made the paintings from afar, creating the portraits over Zoom in her studio in Los Angeles, using photographs to put together two group portraits and 11 paintings of individuals. In a film screened on the Tate website, Nisenbaum says she “think about what [the workers] might be going through, how they must be on the frontline, and how they must be quite afraid”. The book accompanies an exhibition at Tate Liverpool (until 5 September).