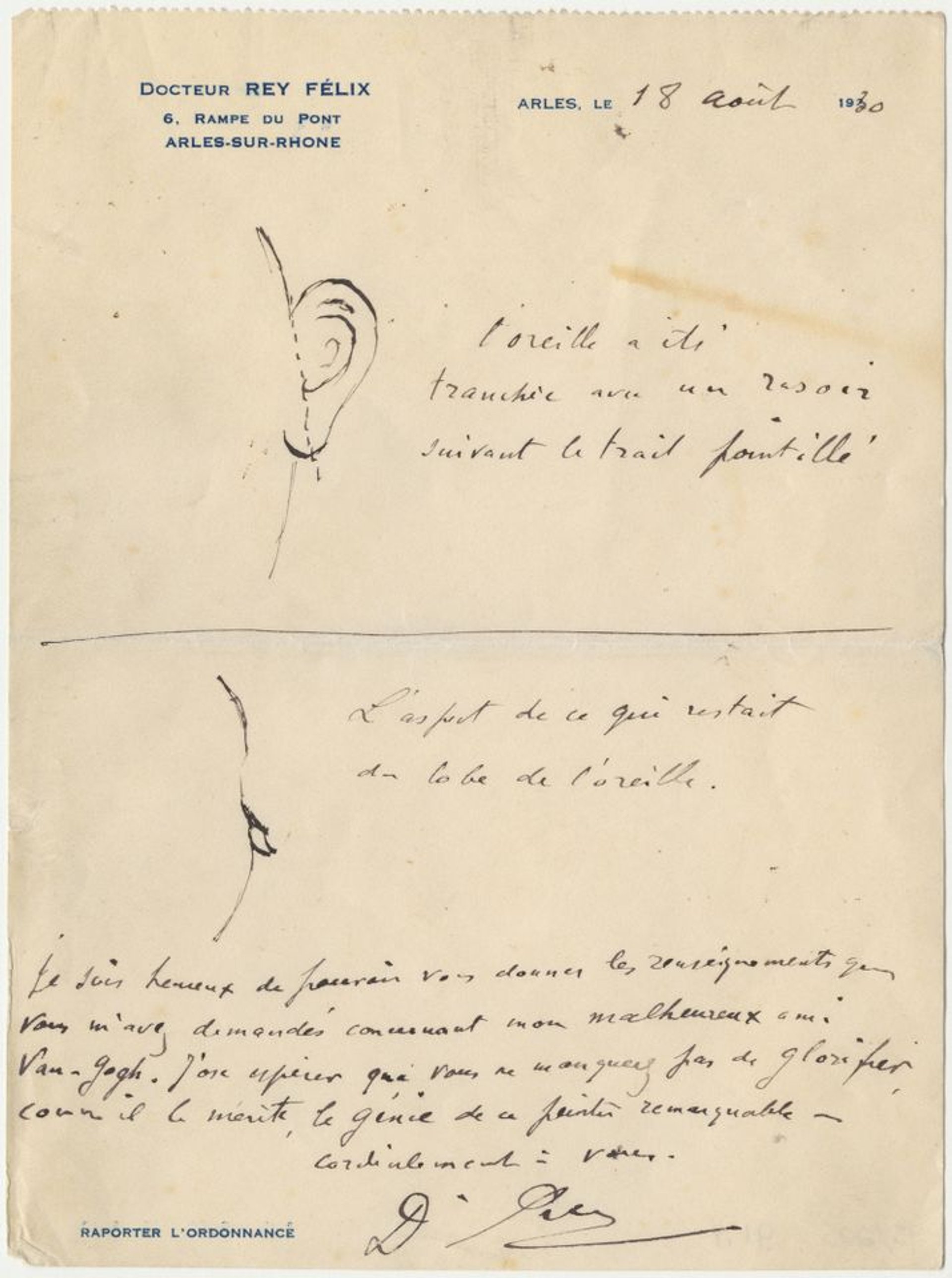

Four years ago Bernadette Murphy’s book Van Gogh’s Ear: the True Story included a scoop: a sketch by the artist’s doctor showing that he had cut off virtually his entire ear. Dr Félix Rey, who treated Vincent van Gogh in the hospital in Arles in 1888, drew it in a 1930 note for the American author Irving Stone, when he was writing his highly successful novel Lust for Life.

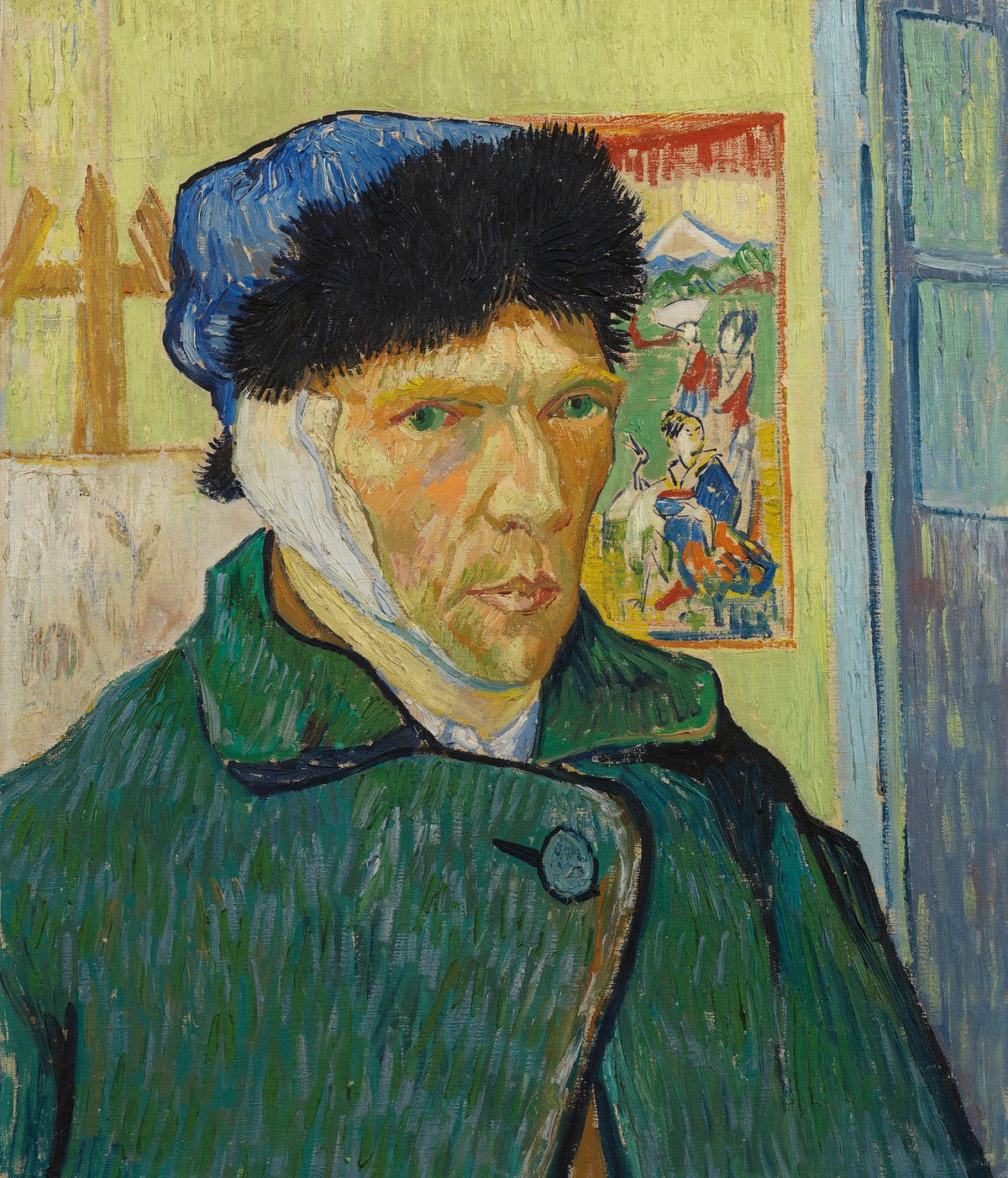

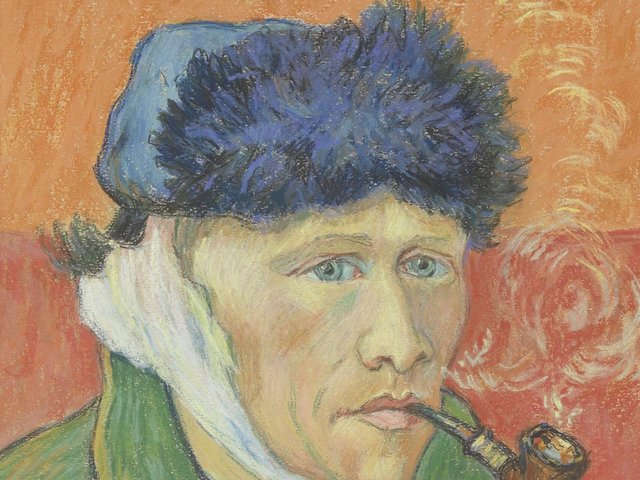

Until Murphy’s well-researched book on the artist’s 15 months in Arles, it was generally accepted that Van Gogh had cut off only part of his ear late in the evening of 23 December 1888 at the Yellow House. Following a confrontation with his colleague Paul Gauguin, Vincent slashed his ear and then walked to a nearby brothel, where he presented the wrapped morsel of flesh to a woman. After Murphy's discovery, the Van Gogh Museum’s authoritative website on the artist’s letters states that he “did indeed cut off his entire ear”. But was Dr Rey’s sketch accurate? And how vital is this to the Van Gogh biographical story?

Note from Félix Rey to Irving Stone with a sketch of Vincent van Gogh’s mutilated ear, 18 August 1930 Courtesy of the Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley

Whether it was the whole ear or part of it is arguably not of fundamental importance, since the main point is that Van Gogh was in such a disturbed state that he severely mutilated himself. But it would still be instructive to know the extent of his injury. If it was the entire ear, it suggests that Van Gogh was determined to cause maximum damage and possibly death. If it was just part of the ear, it could have been more of a plea for help.

Although an undeniably gruesome topic, let’s examine the reports of the key witnesses—starting off with those who said it was only part of the ear, the theory generally accepted until recently.

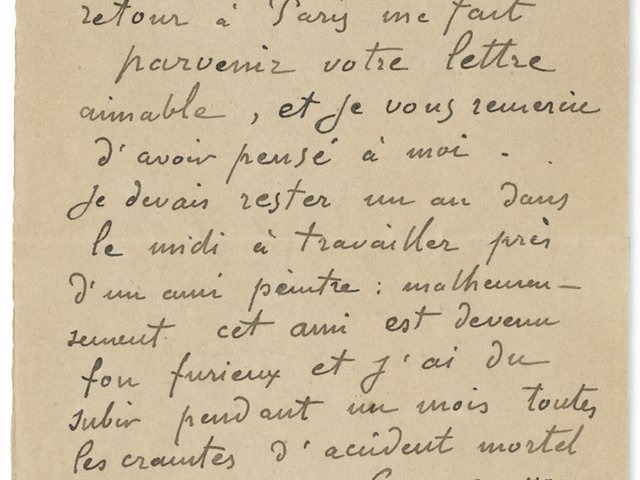

Jo Bonger, Vincent’s sister-in-law, wrote in her memoirs in 1914 that he had “cut off a piece of his ear”. She had met Vincent when he stayed at their Paris apartment for four days in May 1890 and saw him again during two day-visits in June and July. It must have been highly traumatic to see her brother-in-law with the scars, so she would hardly have forgotten the sight. However, she might have had an interest in minimising the severity of the loss to protect the artist’s dignity following his untimely death.

Three months after the mutilation, the artist Paul Signac visited Van Gogh for the day in Arles. In 1921 he wrote to the critic Gustave Coquiot, saying that it was “the lobe of the ear (not the ear)”. Curiously, he recounted that Van Gogh was wearing “the famous headband and cap” and, if so, Signac could not have observed the extent of the loss. However, the wound would have healed weeks earlier, so Van Gogh would presumably not have been bandaged. In his reference to the headband and cap it sounds as if Signac is actually recalling the Van Gogh self-portraits with bandaged ear, rather than his encounter.

Paul Gachet Jr, the son of Dr Paul Gachet (who was Van Gogh’s closest friend in Auvers-sur-Oise and helped care for him after the shooting), had also responded to Coquiot’s enquiries. He wrote that “it was not all the ear—as far as I remember—it was a good part of the outside of the ear (more than the lobe)”. In another letter in the 1930s to two other writers he said it was “not all the ear but a bit more than the lobe”. Gachet Jr, who was aged 17 at the time of Van Gogh’s stay, saw the artist on a number of occasions during his ten weeks in Auvers and it must have been traumatic for a teenager to observe such a terrible scar. He would also have heard the accounts of the incident from his father, who died in 1909.

Although these three witnesses remember it as part of the ear, others recall it as the whole ear.

Gauguin had fled to a hotel a few hours before the incident, but returned the following morning, just before the police arranged for Van Gogh to be taken to hospital. A day later Gauguin returned to Paris and quickly spoke with fellow artist Emile Bernard. In a letter to the critic Albert Aurier, Bernard then wrote that Van Gogh had “cut his ear clean through”—an observation that Gauguin repeated in his 1901 memoirs. But when Gauguin very briefly saw the injured Van Gogh in bed the wound would probably have been roughly covered with a sheet, with blood all around and congealed blood on the wound, so it would have been difficult to determine exactly how much of the ear had been lost.

Alphonse Robert, a policeman involved in the case, wrote in 1929 that it was “the entire ear”. Other witnesses and 1888 newspaper reports refer to Van Gogh cutting off “the ear”, but this rather loose terminology leaves it unclear whether it was all or most of the ear.

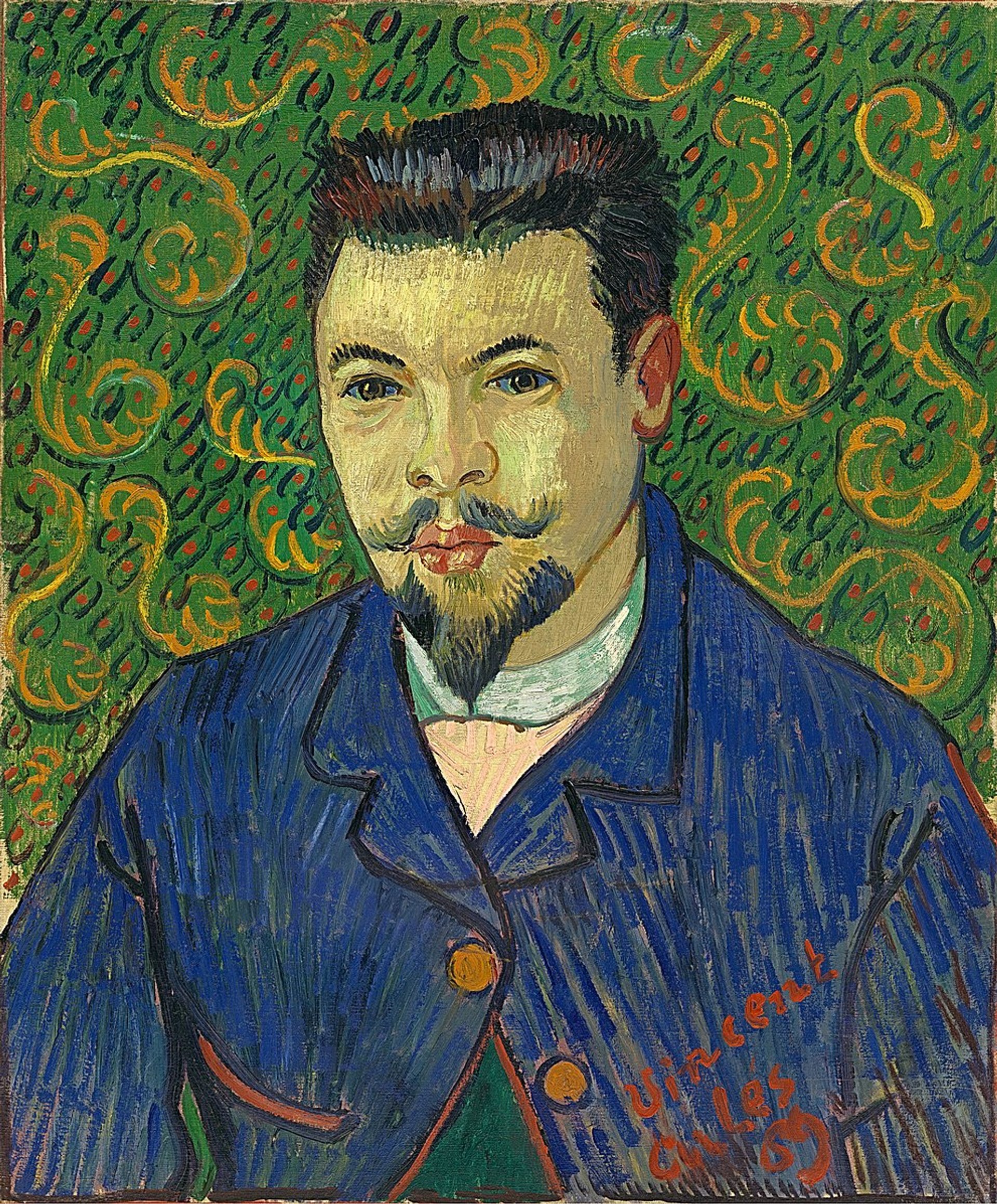

Vincent van Gogh’s Dr Félix Rey (1889) Courtesy of the Pushkin Museum, Moscow

So should we accept the evidence of Dr Rey’s 1930 sketch? He should be a good witness, since he had dressed the wound; as a doctor he should describe medical conditions precisely; and he had had a friendly relationship with the artist. A week after the incident Dr Rey wrote to Vincent’s brother Theo, saying his patient had been unable to explain why he “cut off his ear”—although this phraseology does not necessarily mean that it was the entire ear.

But by the 1920s there are signs that the doctor’s memories of Van Gogh were being distorted as a result of the artist’s international fame and local notoriety in Arles.

A 1928 interview with the art historian Max Braumann and the artist Julius Seyler hardly inspires confidence. Dr Rey described Van Gogh as “a miserable, pitiful man, small of stature”, who always wore an overcoat, “smeared with colours”, since he “painted with his thumb”. This seems incorrect, since his close friend Bernard wrote just a year after Van Gogh’s death that he was “of medium height, stocky but not excessively”. Van Gogh normally used brushes, very occasionally a palette knife, but not his fingers.

The following year Dr Rey wrote in a letter that he had been given the severed ear the day after the incident, but “it was too late to try to reattach it in place”—and he had therefore preserved it in a jar of alcohol. He apparently kept the ear for several years, but it disappeared from his office while he was in Paris.

By far the most detailed early accounts of Van Gogh’s medical condition were written by Dr Victor Doiteau and Dr Edgar Leroy, who contacted the key witnesses who were still alive in the 1920s. They concluded in a detailed 1936 article that the upper part of the ear (perhaps just over half) had been removed.

To sum up, the evidence about the extent of the mutilation is frustratingly unclear. Many of the witnesses may have had an interest in either minimising or maximising the loss, depending on whether they had been close to Van Gogh and wanted to present him as more sane or if they had an interest in being linked with the increasingly famous “mad” artist.

My personal feeling, after analysing the surviving evidence, is that it was much and perhaps most of the ear—but certainly not all of it.

Other Van Gogh news

• The exhibition Laura Owens & Vincent van Gogh, scheduled to open at the Fondation Vincent van Gogh Arles on 16 May, has now been postponed until spring 2021 because of coronavirus. It will feature work by the Los Angeles painter Owens, inspired by Van Gogh.

• The Kröller-Müller Museum in Otterlo, which holds the world’s second greatest collection of Van Gogh works, has just published its first book which reproduces the 88 paintings and 180 works on paper in colour in a single volume. Vincent van Gogh: All Works in the Kröller-Müller Museum is a good-value picture book, with a brief text.