The US Supreme Court has decided that it is constitutional for Congress to require the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) to consider “decency” in awarding arts grants. The decision, announced 25 June, closes the final appeal which sought to resolve whether the decency test, imposed by Congress in 1990, violates the American Constitution’s prohibition against laws “abridging the freedom of speech.”

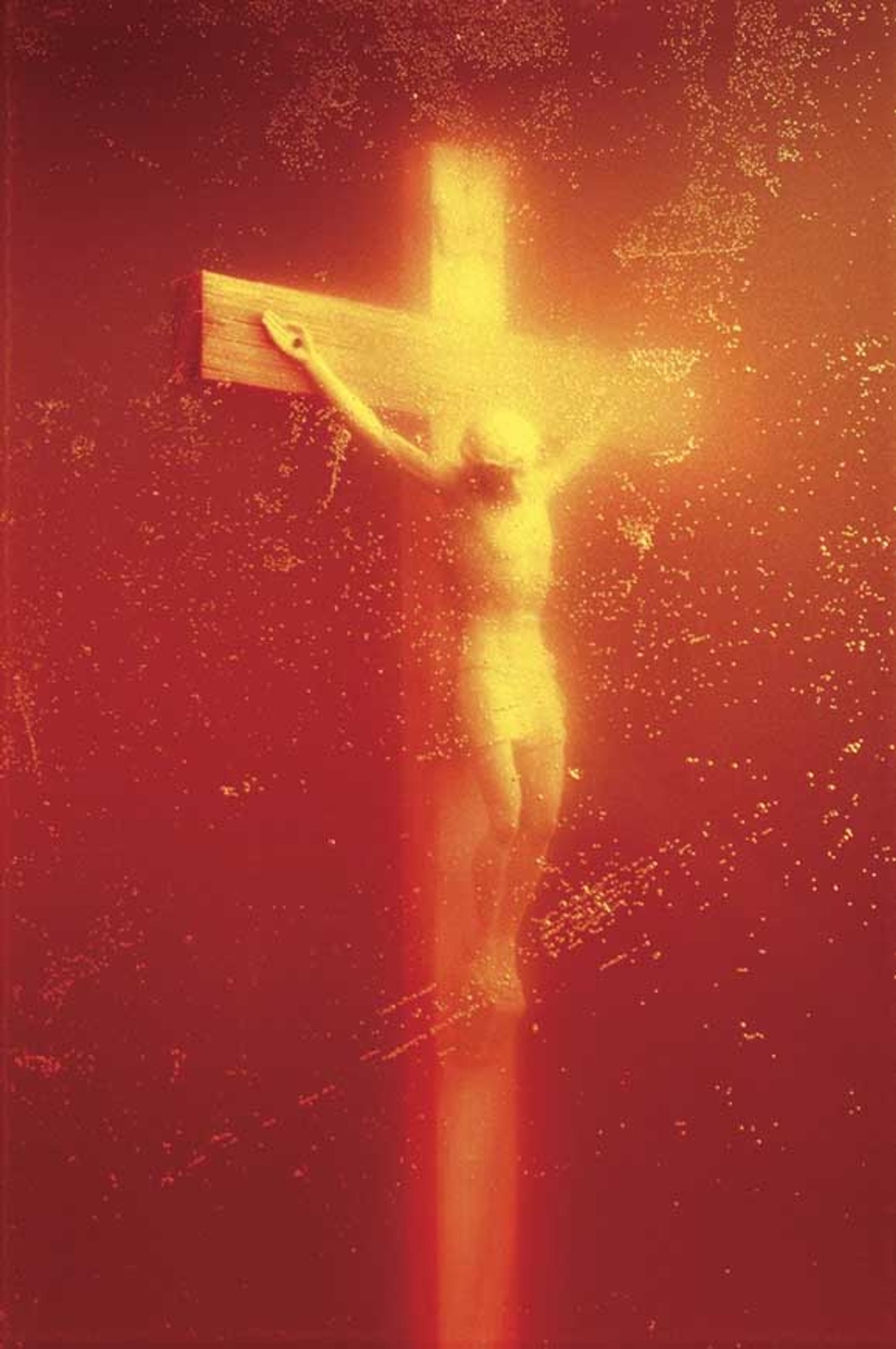

In 1990, the US Congress, angered that NEA grants had funded homoerotic photographs by Robert Mapplethorpe, and Andres Serrano’s photograph of a crucifix in his own urine, enacted new restrictions on NEA grantmaking, requiring the agency to consider “general standards of decency and respect for the diverse beliefs and values of the American public.”

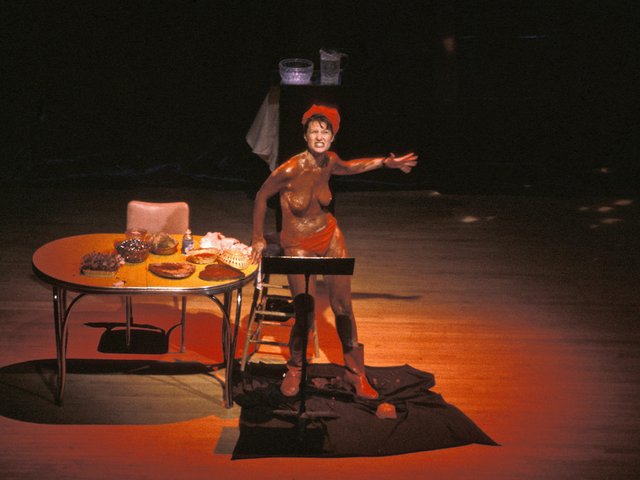

Four artists challenged the statute, successfully overturning it in two lower federal courts in California. One artist, Karen Finley, had sought funds for a performance in which she “recounts a sexual assault by stripping to the waist and smearing chocolate on her breasts, and by using profanity.” Another of the artists, John Fleck, sought funds for a performance in which he “appears dressed as a mermaid, urinates on the stage and creates an altar of a toilet bowl by putting a photograph of Jesus Christ on the lid.”

The decency test was allowed to stand because the Court found it “merely hortatory”—meaning more an exhortation than a requirement. There is “no categorical requirement” that art be decent, the Court said, in a decision written by Justice Sandra Day O’Connor. She called the decency standard “advisory.” And the law’s political history showed it was not intended as a free speech gag, the decision said.

Avant-garde artistes remain entirely free to épater les bourgeois; they are merely deprived of the additional satisfaction of having the bourgeoisie taxed to pay for it.Justice Antonin Scalia

Justice Antonin Scalia, a conservative who agreed with the majority, wrote a separate opinion in which he called Mapplethorpe’s homoerotic photographs “lurid.” He said that the decency test did establish viewpoint discrimination by favouring grant applications displaying decency and respect—a discrimination he called constitutional. He added that the decency test did not “abridge indecent speech,” but merely meant the government did not have to pay for it.

“Avant-garde artistes,” he said, “remain entirely free to épater les bourgeois; they are merely deprived of the additional satisfaction of having the bourgeoisie taxed to pay for it.”

This seems to have been the nub of the issue. Indeed, at oral argument in the case in March, Justice O’Connor asked whether Congress had to pay for art it disapproved of. The Court said in the decision that because the decency test is for a government subsidy, Congress could set a criterion that would be impermissible if it were trying to restrict speech directly, or setting a criminal penalty.

A plaintiff who argues that a US law violates the American Constitution must establish either that the law is unconstitutional on its face—meaning it cannot be applied constitutionally in any circumstance—or, that it was unconstitutional as applied to the plaintiff. The artists, who were denied grants but received settlements, raised the “facial” challenge, meaning they had to prove “a substantial risk” that application of the law would “lead to the suppression of free speech.”

Andres Serrano, Piss Christ (Immersions) (1987) © Andres Serrano. Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Nathalie Obadia Paris/Brussels

The Court said the danger to free speech was not clear enough given the advisory nature of the decency test. Since NEA grants also go to symphony orchestras and school programmes, where the decency test either would not apply or would be constitutionally permitted, the artists had not proved that the law could not be constitutionally applied.

But the Court said that the lawsuit did not arise from denial of a grant due to “invidious viewpoint discrimination.” This may leave the door open to a future challenge from artists whose projects are denied on grounds of decency—perhaps in a case where “decency” can be shown to be a subjective evaluation.

A lone voice of opposition was heard from Justice Souter. The evidence was “damning,” he wrote, that Congress had adopted an impermissible regulation of speech because of disagreement with the message. Quoting from a 1996 decision of the Court, he said that “‘Indecency often is inseparable from the ideas and viewpoints conveyed.’”

The NEA, which defended the decency test in the lawsuit, now finds recent turmoil settling in a second area: funding.

Republicans in the House had sought to eliminate the NEA since taking over Congress in 1995, and in 1996 reduced its budget 40%, planning to phase it out. But in July, the House voted money for the agency, reflecting sensitivity to the November elections.

• This article originally appeared in The Art Newspaper with the headline "Carry on shocking—but the bourgeois need not pay"